RECOMMENDED READING

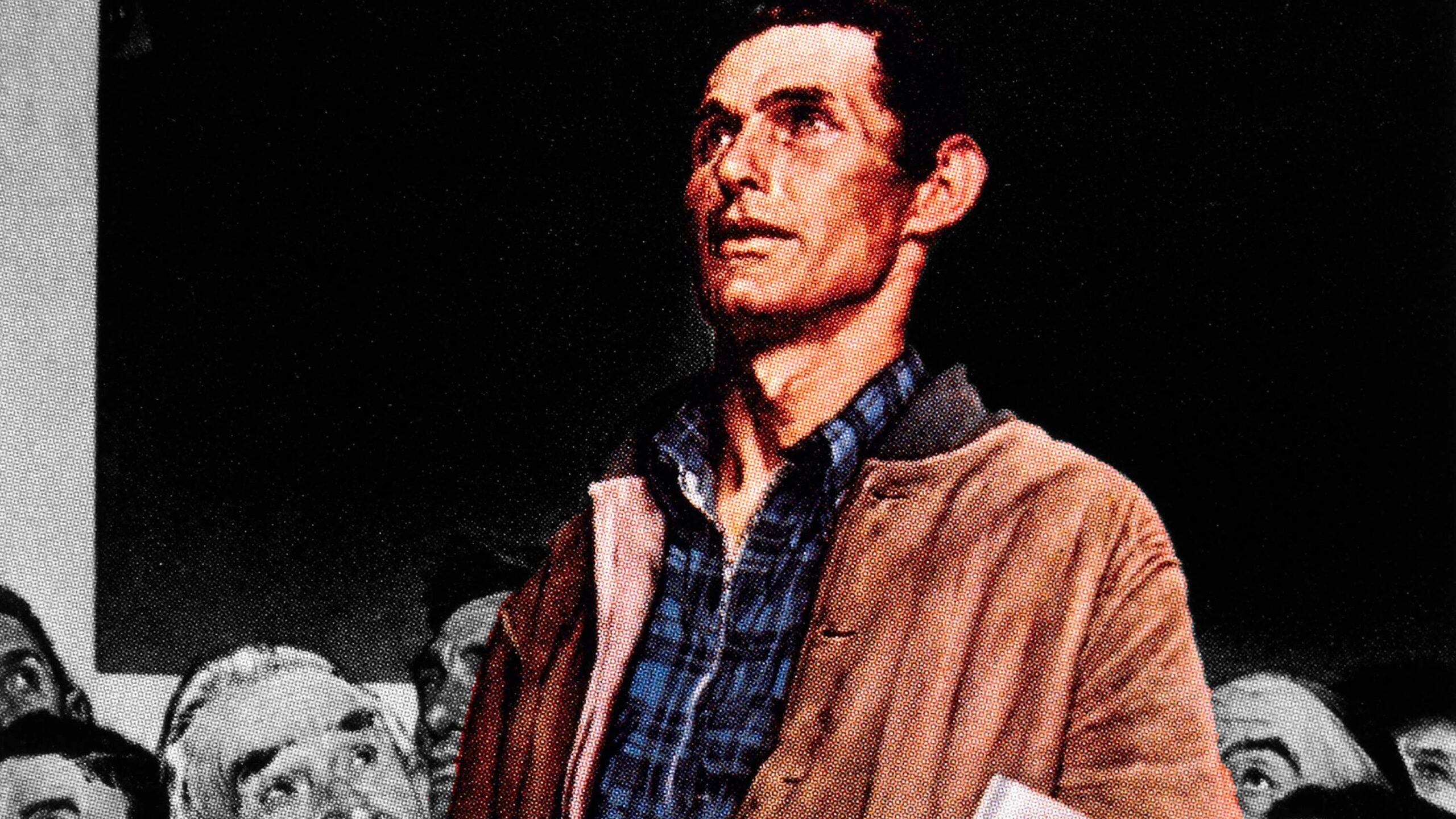

In D.C. circles, you often hear pundits and organizers talk about the difference between an actual “grassroots” movement and its evil cousin, “astroturf,” a manufactured facsimile to advance a top-down agenda. Halfway between artifice and authenticity, you might come across the “bonsai trees,” those prized specimens painstakingly manicured to give just the right effect. At a hearing or lunchtime panel, you might hear from a low-income mom who benefitted from a tax credit program being pushed by an advocacy organization, or a farmer whose daily concerns are shoehorned into a discussion about agriculture subsidies.

To be sure, these are real people with stories that intersect with various facets of public policy. But when working-class Americans are heard in policy circles, they too often tend to be props flown in for a hearing, carefully positioned next to the podium at a rally, or quoted in soundbites served up by an interest group with an axe to grind. Their own perspectives are sanitized and pre-packaged, not taken as what they are—messy, at times contradictory, but more than just a stand-in for a pre-existing agenda.

“…when working-class Americans are heard in policy circles, they too often tend to be props flown in for a hearing, carefully positioned next to the podium at a rally, or quoted in soundbites served up by an interest group with an axe to grind.”

As the editor of the Edgerton Essays project, published by American Compass in partnership with the Ethics and Public Policy Center, I naively thought our project would be a fairly simple one. First, find working-class Americans, typically without a four-year college degree, who felt distant from the political discourse and eager to share their thoughts. Second, give them a simple prompt, typically an open-ended invitation to tell politicians what they didn’t understand about the challenges facing their communities. Third, work with them to hone their contribution in terms of organization and clarity while preserving their voices and perspective—no editing for party line or area of emphasis. Fourth, publish them, promote their work, and pay them as we would any other contributing writer.

The first step proved the hardest. The loss of social capital and dissolution of civic institutions that have especially plagued pockets of working-class America left distressingly few opportunities for reliable outreach. The same social facts that leave working-class communities vulnerable—unpredictable work schedules, declining church attendance, less community involvement—also mean a paucity of union leaders, pastors, fraternal organizations, or local newspapers to pass the word along.

Even when we found writers, more than a few felt they couldn’t follow through. In our polarized age, people were uncomfortable sharing their honest opinions about work and welfare, family and community, for fear of losing friends or alienating employers. The essayists who published with us did so without a pseudonym or anonymity, and while it shouldn’t have to take an act of bravery to share thoughts publicly, for many it was, and we’re grateful.

These essays captured the unfiltered thoughts of working-class Americans in all their complicated diversity. We heard from former felons, grandmothers, nurses, veterans, and farmers. We heard calls for more money for child care assistance and more support for stay-at-home moms, for policymakers to give families more support and for them to get out of the way, for less regulation and more mandates, for more safety-net spending and less social spending that threatens entitlements. We heard evidence to suggest that a working-class agenda should focus on pocketbook issues and essays that stressed a robust cultural push.

“These essays captured the unfiltered thoughts of working-class Americans in all their complicated diversity.”

Most strikingly, and in contrast to the pre-packaged “voices” typical in political media, almost none of our essayists spoke in terms of “policy principles.” With apologies to the 1970s feminists, in these essays the personal doesn’t feel political. The issues that get cable news play and attract fundraising dollars feel almost wholly distinct from the day-to-day reality of trying to pay the rent or get mental health assistance. Ideological fights over climate change and border walls left authors wondering when politicians would focus on making it easier for them to make ends meet. They thought in terms of “politicians,” not “policymakers,” and most often just wanted a government that simply works and pays attention to their concerns.

“Feeling heard” is an admittedly nebulous concept. Appeals to cultural affinity are obviously a shorthand way to try to create this bond. But the demand here tended to be that representatives spend more time “getting to know us a little,” as one writer put it, and less time on the rubber chicken circuit. Chambers of Commerce and identitarian activists are good at creating breakfast roundtables or town hall meetings to showcase a certain set of voters (or donors). Political leaders, researchers, and commentators will all need to work harder if they want to understand the daily concerns of politically disconnected voters in the middle of the income distribution and develop an agenda that speaks to them.

I will be the first to admit that such an agenda will not earn headlines, clicks, or retweets. It may not even win a primary. But for a “populist” agenda to be more than a noisy veneer on pre-existing preferences, partisans of the right and left need to recognize the distance between their favored narratives and the ones that keep working-class Americans up at night. A candidate who focused on making health care less administratively burdensome, the schools a little more responsive, or rental assistance a little easier to navigate, might give some of our essayists, at least, a sense that someone is actually listening.

Recommended Reading

Working Americans Are Speaking. Are Politicians Listening?

In an adaptation of his conclusion to the Edgerton Essays anthology, Patrick T. Brown discusses what he learned from editing the collection of perspectives from the working class.

The Edgerton Essays

Perspectives from the Working Class

Introducing the Edgerton Essays

The goal of these essays is to help inform policymakers and pundits about what matters most and why to the vast majority of Americans who have no day-to-day connection to our political debates.