On contributory social insurance and the American work ethic

RECOMMENDED READING

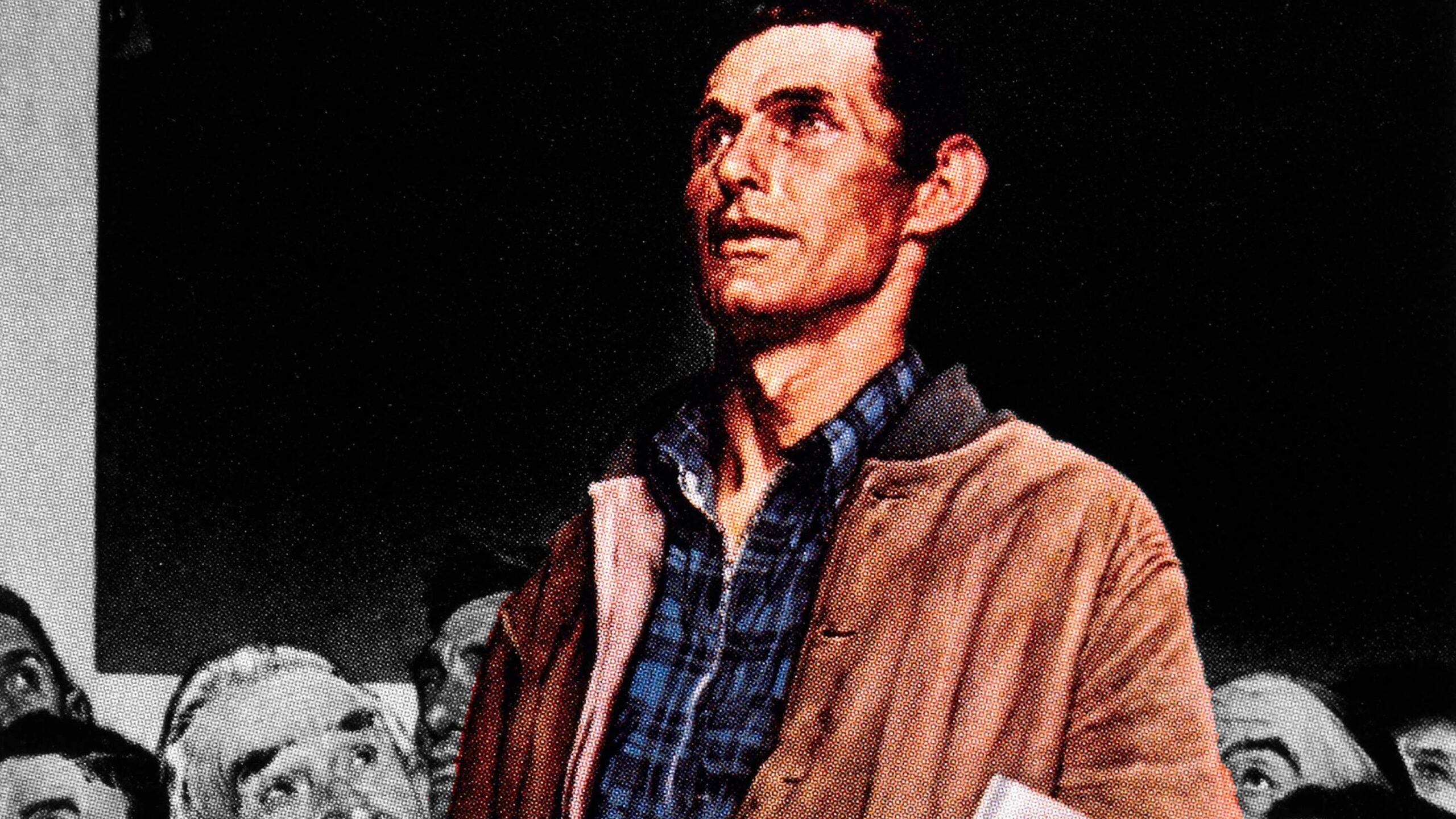

There are two kinds of people: those who want politicians to “keep your government hands off my Medicare,” and those who think that’s the dumbest thing they’ve ever heard. When an angry constituent made the declaration at a town hall meeting convened by Rep. Bob Inglis during the 2009 health care debate, pundits across the political spectrum seized on it to symbolize the lamentable ignorance of ordinary people in general and populist conservatives in particular. On the right, George Mason economist Tyler Cowen called the remark, “The funniest sentence I read today.” On the left, Slate’s Timothy Noah announced his initiative “to combat the pernicious and big-babyish meme that Medicare lies beyond government control and must remain so.”

With its supercilious mockery, the overclass intelligentsia revealed an inability to distinguish between social assistance and social insurance, which both market fundamentalists on the right and socialists on the left regard as interchangeable for ideological reasons. The market fundamentalist evaluates public programs on the starkly utilitarian basis of how much monetary value flows to whom, without regard to moral justification. The socialist obsesses over moral justification but embraces a framework in which all are equally deserving of public support. To both groups, then, money is money, whatever its source. People pay the taxes they can afford and receive the benefits they need.

Most Americans disagree. Along with citizens of other modern democracies, they see a profound moral and political difference between non-contributory social assistance paid out of general tax revenues (“welfare”) and contributory social insurance funded by payroll taxes or premiums (“earned benefits”), even if both kinds of programs involve government spending. Medicare may be administered by the government, but it is a program of, by, and for the working people who pay for and receive it.

Underlying this disconnect in thinking about the welfare state is a debate between two moral systems, which might be called the work ethic and the consumption ethic. The work ethic views membership in a community as entailing a reciprocal obligation to contribute through personal effort—whether paid or unpaid—to the community’s flourishing, rather than exploiting others by free-riding on their efforts. The consumption ethic in contrast views work as merely a means to the end of personal consumption, with no intrinsic value to distinguish it from other sources of income that allow for enjoyment of the same consumer goods—private charity, government welfare, or capital gains derived from the passive ownership of assets that generate profits, rents, or interest.

“Medicare may be administered by the government, but it is a program of, by, and for the working people who pay for and receive it.”

From each perspective, the policy prescriptions of the other can seem outlandish. And with most Americans in the work ethic camp, and many who aspire to govern them in the consumption ethic camp, the miscommunication easily gives rise to frustration and hostility. Many of the nation’s sharpest policy debates—over entitlements, health care, childcare, child allowances, and welfare—are surrogates for this clash of ethical systems. Consumption ethic economists have reams of evidence that handing out money to the poor “works,” by which they mean tautologically that it hands people money. Anyone who disagrees, they conclude, must be foolish, selfish, or perhaps racist.

This does not persuade anyone, nor should it. The predominance of the work ethic is a fact of American culture and a constraint within which policymakers must operate. Programs that flout a culture’s core values rarely endure or succeed. Nor should policymakers want those values to change. The attachment of pride and status to individual effort promotes worthwhile social goals, including widely shared economic growth.

The path to a more secure and generous American welfare state lies not in rejecting the work ethic and the distinction it makes between contributory social insurance and non-contributory social assistance, but rather in embracing it. An agenda that spends more of the money of the rich on the poor is understandably of little interest to the vast American middle. The goal should be to help all adults who can work to earn enough not only to support themselves and their families without means-tested social assistance but also to contribute to the funding of programs of mutual support that provide financial and social security.

* * *

The work ethic is ancient and continues to dominate the thinking of most citizens in modern democracies about government aid to individuals. The term “Protestant work ethic,” popularized by Max Weber, is misleading, insofar as it implies that most Catholics, Jews, Muslims, Hindus, and Confucians have been indolent by comparison. In fact, only a tiny minority of aristocrats and rentiers have ever been able to live without laboring to meet their material needs, along with those of their community, whether an egalitarian village or a hierarchical despotism. Once-fashionable claims that Stone Age hunter-gatherers worked only a few hours per day and led lives of leisure compared to people in agrarian and industrial societies have been criticized by recent scholarship. Among ordinary people worldwide, the work ethic is a universal tradition.

Long before widespread social insurance emerged as a phenomenon of modern industrial economies with wage-earning majorities, the work ethic shaped the rudimentary social assistance that premodern communities provided to people in need. This assistance drew clear lines between the “deserving poor”—those who cannot contribute to their own subsistence—and the “undeserving poor”—those who are idle and dissolute but capable of working. The Elizabethan Poor Law, for instance, distinguished between the deserving poor who should be taken care of by the community, whether by public provision or private charity, and “sturdy beggars” who should be compelled by economic privation or government compulsion to work toward supporting themselves and their families. The American colonies inherited this approach from Britain.

Beginning in the eighteenth century, however, humanitarian reformers, classical liberals, and some socialists rejected the work ethic for a version of utilitarianism that erases the distinction between the deserving and undeserving poor. Starting from varied philosophical premises, these groups all reached the conclusion that whether money is earned by personal effort is irrelevant. The important thing is to guarantee everyone a minimal income to be able to enjoy a minimal standard of living, defined as a certain level of consumption. This version of the consumption ethic fits nicely with the view of classical and neoclassical economics that work has no value in itself; it is merely a means to the end of personal consumption, and indeed belongs on the cost side of the ledger. Thus, no stigma should accompany unearned income, whether it takes the form of government handouts to the idle poor or passive rents to landlords, money-lenders, and capitalist investors—all groups viewed with suspicion by adherents of the work ethic like 19th-century American Populists, who warned of the growth of “the two great classes—tramps and millionaires” in the 1892 platform of the People’s Party.

With the industrial revolution came a new category of public support: social insurance. In premodern agrarian societies, the recipients of social assistance tended to be a small number of destitute, landless laborers and their families, to whom local elites provided necessities or jobs. As a result of industrialization and urbanization, however, most people became wage earners or their dependents. These households had to pay cash for rent, food, clothing, and medical care, and could no longer rely on subsistence agriculture or domestic crafts if the breadwinner was unemployed.

For the typical worker, wages have always been too low to permit for saving in advance for all possible emergencies. Instead, the sensible and highly valued option for wage earners is to acquire insurance against unlikely and unaffordable costs like a health crisis on one hand and the prospect of income loss from unemployment or disability on the other. In some instances, these insurance products are available and indeed are purchased on the private market. But in many others, failures of insurance markets make provision implausible or prohibitively expensive.

One response in the early industrial era was the development by workers themselves of “friendly societies” or nonprofit mutual aid societies. These membership organizations, often with colorful names like the Ancient Order of Foresters or the Odd Fellows or the Shriners (Freemasons), combined the functions of modern insurance for sickness, burial costs, old-age assistance, and other expenses with the social activities of modern guilds, like regular feasting and parades. But many workers could not afford to pay dues, and nonprofit mutual aid societies often excluded people in poor health or poor financial condition to avoid adverse selection, just as commercial insurers did.

Social insurance works well only if participation is universal or near-universal, which in many cases necessitates state-compelled membership in contributory systems. If not paying premiums is an option, then the exit of the affluent and young can create a death spiral into insolvency for social insurance, just as for commercial insurance, where a dwindling number of sick and elderly people can face ever-higher premiums. For this reason, most industrial nations with wage-earning majorities adopted systems of social insurance administered by the state (although relics of mutual aid societies survive in the German sickness funds and the Ghent system of union-administered benefits in Sweden and Czechoslovakia).

But the divide between the work and consumption ethics has yielded competing visions for social insurance: the Bismarckian and the Beveridgean. The Bismarckian model, named after the chancellor of Imperial Germany who pioneered the modern welfare state to weaken the appeal of socialism to the working class, is modeled on private insurance. Bismarckian social insurance is based on contributory taxes, usually payroll taxes, and workers who contribute more receive higher benefits.

The rival model of social insurance is named after the British liberal economist William Beveridge, whose November 1942 report set forth the “Beveridge Plan” for the post-war British welfare state, a vision never completely realized in the United Kingdom or elsewhere. In the Beveridge model, public payments for health care, public pensions, unemployment insurance, and the like come out of general taxes, similar to spending on defense or infrastructure or public education. The payments to citizens should be flat and identical for all, regardless of income, or else based solely on need.

The American social insurance and assistance programs established by the New Deal in the 1930s—Social Security, unemployment insurance, disability insurance, and Aid to Dependent Children (ADC)—for the most part embodied the work ethic by creating earned benefits with eligibility based on a history of work and payroll tax contributions. ADC was designed explicitly as a program for the deserving poor on the work ethic model of social assistance, targeting widows with children in an era that took the assumption of a male breadwinner for granted.

The “War on Poverty” of the 1960s took a very different approach. ADC became AFDC (“Aid to Families with Dependent Children”) and changes in both social context and policy design shifted the program’s clientele to never-married single mothers who were widely seen as capable of working to support themselves. The program’s social assistance was no longer consistent with the work ethic and became deeply unpopular. Public outrage at federal funding of single parents with children who did not work or have a working spouse led to the abolition of AFDC and its replacement by Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF). The very features that made consumption ethic intellectuals denounce TANF as inhumane—time limits on welfare use and a requirement on adult welfare recipients to seek a job—reflected the work ethic values of the American majority, as well as their insistence on distinguishing between a stay-at-home parent supported by a spouse and one supported by the taxes of unrelated fellow citizens.

Conversely, the New Deal’s contributory social insurance programs remain popular and consumption ethic complaints have generally fallen on deaf ears. Criticism of Social Security from the market fundamentalist right and the socialist left mirror perfectly their respective blind spots when it comes to the merits of its model.

“Both anticipated Social Security benefits and 401(k) accounts represent claims by retirees on the economic activity of workers. In both cases, it is the surplus produced by today’s workers that lands in the pockets of retired former workers.”

Market fundamentalists fail to appreciate the advantages that government can offer over the market when it comes to a task like long-term saving and are forever proposing to replace modern systems of social insurance with tax-favored savings accounts. But the idea that Social Security’s dependence on future politics is a weakness, while tax-favored IRAs and 401(k)s have the advantage of being “your money,” is doubly confused. First, “your money” remains subject to future politics, too. A federal government in financial straits is more likely to tax IRAs and 401(k) accounts, which chiefly benefit the affluent, than to cut benefits to Social Security, a popular program on which most citizens rely. Second, both anticipated Social Security benefits and 401(k) accounts represent claims by retirees on the economic activity of workers. In both cases, it is the surplus produced by today’s workers that lands in the pockets of retired former workers. If the economy collapses, both Social Security and mutual funds will be in dire condition. The difference is that a sovereign territorial state that can extract taxes from a diverse economy or borrow from lenders around the world is more likely to meet the expectations of retirees in a crisis than is some pile of corporate equities.

Meanwhile, socialists failing to appreciate the contributory premise of Social Security see its funding structure as “regressive.” In 2021, wage earners pay payroll taxes only on the first $142,800 of labor income, and they pay no Social Security taxes at all on non-labor income like that from capital gains. Someone earning $500,000 pays only three times the taxes of someone earning $50,000, despite having ten times the income. And at the margin, the higher earner pays nothing on the next dollar earned above the limit while the lower earner still owes the full rate on additional work income.

The regressive nature of the payroll tax cap is a “feature” of Social Security, not a “bug,” to use the lingo of the tech sector. Like other Bismarckian social insurance programs, the American Social Security system mimics voluntary systems of mutual aid set up by working-class citizens. Although it has redistributive elements, it is not supposed to be a social assistance program based on redistribution from the rich to the poor. In its ideal form, contributory social insurance funded on a pay-go basis is a system of horizontal transfers from today’s workers to those of their own class who cannot work because they are old, sick, disabled, or temporarily unemployed. Anyone rich or poor may participate, but they do so on the same terms, making the same payments in to get the same benefits out. Conversely, the rich are under no special obligation to fund the system and hold no leverage in a threat to opt out.

“Far from mocking the individual who said, “Keep your government hands off my Medicare,” FDR would have been delighted.”

Franklin Roosevelt explained his preference for a contributory social insurance system to Luther Gulick, an economist who advised the federal government, in the summer of 1941. When Gulick, like many economists then and now, complained that the payroll tax was a regressive tax on workers, FDR replied:

I guess you’re right on the economics. They are politics all the way through. We put those pay roll contributions there so as to give the contributors a legal, moral, and political right to collect their pensions and their unemployment benefits. With those taxes in there, no damn politician can ever scrap my social security program. Those taxes aren’t a matter of economics, they’re straight politics.

Far from mocking the individual who said, “Keep your government hands off my Medicare,” FDR would have been delighted. Like Social Security, Medicare was designed by FDR’s protégé and successor Lyndon B. Johnson to be an earned benefit based on years of work effort via payroll tax contributions.

* * *

On a range of issues, market fundamentalists and socialists have tended to reject Bismarckian social insurance coupled with workfare in favor of Beveridgean universal income schemes which erase distinctions that are important to the work ethic—distinctions between social insurance and social assistance, between contributory taxes and general taxes, between the deserving and undeserving poor, between individuals supported by other family members and individuals supported by the taxpayers at large. Libertarians like Milton Friedman and Charles Murray, along with many on the left, have favored replacing both social insurance and social assistance with a universal basic income in the form of direct cash handouts—in Friedman’s case, in the form of a “negative income tax.”

But despite having a work requirement, President Nixon’s proposal in 1969 for a negative income tax as part of his Family Assistance Plan never passed the Senate. Democratic presidential candidate George McGovern’s proposal in 1972 for a “demogrant” of $1,000 for every American (more than $6,000 in today’s dollars) flopped as well, as did candidate Andrew Yang’s similar “Freedom Dividend” during the 2020 Democratic primaries and the 2021 New York Democratic mayoral primary race. Instead, Congress created and has expanded the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), which has been popular with Democratic and Republican voters, if not libertarian and leftist policy wonks, precisely because it links means-tested assistance to work effort on the part of the recipient.

Disagreements about the desirability of a universal basic income reflect class as much as ideology. The UBI concept appeals to affluent rentiers with non-labor income—like tech executives whose fortunes are based on intellectual property rents, financiers who rake in fees and interest payments, and old-fashioned landlords, of whom John Stuart Mill remarked contemptuously, “They grow richer, as it were, in their sleep, without working, risking, or economizing.” The vision of society as a cornucopia of unearned cash also appeals to many nonprofit grantees and academics who live on gifts by rich philanthropists or on the capital gains from university and foundation endowments. It is natural for them to ask, why can’t everyone be a rentier or a grantee like me?

The difference between contributory and non-contributory approaches both to social insurance and social assistance explains the divides in contemporary debates over childcare and government aid to caregivers. For believers in the work ethic, it makes perfect sense to add earned benefits like both a child benefit and a conceptually different parental caregiver benefit for an at-home parent to the existing list of contributory income maintenance programs, including Social Security, unemployment insurance, and disability insurance. In the spirit of contributory social insurance, a program that allows one of two parents to raise children at home, or allows both to work part-time, should be paid for wholly or in part by a payroll tax on the work of one or both working parents or another working family member.

“Adherents of the work ethic, and normal human beings in general, distinguish between stay-at-home parents married to working spouses and stay-at-home single parents married to the federal government.”

This traditional social insurance approach would not be a problem in the case of a one-earner, two-parent family. But it is a problem in the case of single parents, usually single mothers. Adherents of the consumption ethic on the left, and presumably libertarian supporters of basic income as well, assert that it makes no difference whether benefits for children are linked to work by someone in the family or not; either every individual parent should have to work to receive support, or none should. Adherents of the work ethic, and normal human beings in general, distinguish between stay-at-home parents married to working spouses and stay-at-home single parents married to the federal government.

Equally perverse is the “workist” alternative, in which all parents of children, including the mothers of infants, are encouraged to be in the workforce, with their children raised by strangers in institutional commercial or public daycare. This is the policy promoted by employer lobbies that seek to increase profits by expanding the workforce rather than raising labor productivity, and their allies among elite “corporate feminists.” The “maternalist feminists” like Eleanor Roosevelt, who favored protective legislation for mothers, would have been horrified by this unholy alliance against the family. So would the great labor activist Mary Harris “Mother” Jones, who declared that she was inspired to devote her life to the trade union movement in the hope that employers would pay men wages high enough that their wives could take care of their children without working.

Whatever the post-familist American intelligentsia thinks, the American electorate is unlikely to approve of paying single parents with children to stay at home, even if the same voters favor benefits for stay-at-home parents in one-earner, two-parent families. Only from the perspective of the consumer ethic, in which “money is money” regardless of its source and individuals apart from their families should be the subjects of public policy, is there a contradiction in favoring aid to married homemakers but not to single parents. From the perspective of the work ethic, the distinction is as sensible and important as that between the deserving and the undeserving poor. Society can and should be generous to single parents while promoting intact families with children as the ideal.

According to the work ethic shared by traditional labor liberals, conservative populists, and familists alike, the problem with the American welfare state is not that it is too big overall, but that social insurance is too small and social assistance is too big. The work ethic ideal is an economy in which high wages can support the high payroll taxes needed to support a contributory social insurance system, including social insurance payments for children and their parental caregivers. The combination of high market wages and generous contributory social insurance programs could also permit the downsizing of means-tested social assistance or “welfare,” especially for those who can work. They should be given “workfare” jobs by the government or the private sector, perhaps in a few cases with public wage subsidies (though these must be limited to prevent employers from exploiting them).

“The problem with the American welfare state is not that it is too big overall, but that social insurance is too small and social assistance is too big.”

When it comes to work and welfare, the instincts of untutored working-class people are sounder than the ideologies of libertarians, socialists, and neoclassical economists. Performing work that is useful to society and supports one’s own family has intrinsic value; it is not merely a means to consumption no different in moral terms from government handouts or returns on capital investments. Earned benefits and poor relief are two different things. Unconditional cash relief for those who cannot work is necessary, but it is corrupting and demoralizing for those able to contribute to society and support themselves with their own efforts. Social Security and government-favored private retirement programs, unemployment insurance, and disability insurance should be based chiefly if not exclusively on work-related taxes or premiums. They should be thought of as state-coordinated mutual aid for a well-paid, independent, working-class majority, not as government programs paid for by the beneficence of the rich.

The combination of a family wage with contributory social insurance has never lost its appeal to the working-class majority in modern democracies. In this case, the policies that are best are those that are popular.

Recommended Reading

The Edgerton Essays

Perspectives from the Working Class

Introducing the Edgerton Essays

The goal of these essays is to help inform policymakers and pundits about what matters most and why to the vast majority of Americans who have no day-to-day connection to our political debates.

Conclusion to the Edgerton Essays

These essays captured the unfiltered thoughts of working-class Americans in all their complicated diversity.