RECOMMENDED READING

Recently, I suggested that the United States would do well to emulate some aspects of China’s economic development model, largely on the grounds that this still constituted the optimal route to reindustrialization. If done correctly, reindustrialization can provide a key means of generating high quality jobs in the U.S. and a corresponding break from today’s prevailing market fundamentalist model characterized by precarious employment prospects, wage stagnation and the loss of many of the attributes long associated with a prosperous and stable middle class.

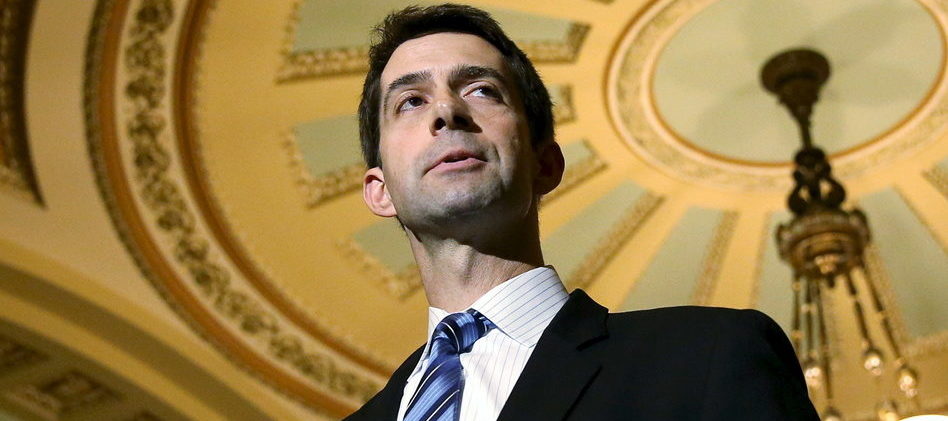

Happily, the U.S. government is beginning to take concrete steps in this direction, with the introduction of Senator Tom Cotton’s new bill focusing on domestic production of semiconductors, titled the “American Foundries Act of 2020.” The bill has received significant bipartisan backing as evidenced by the co-sponsorship of Senators Chuck Schumer (D), Marco Rubio (R), Josh Hawley (R), Jack Reed (D), James Risch (R), Kirstin Gillibrand (D), Susan Collins (R), and Angus King (I). The bill proposes spending up to $25 Billion in three major categories: $15bn for commercial microelectronics manufacturing, $5bn for defense microelectronics grants, and a final $5bn un R&D spending to secure U.S. leadership in microelectronics.

That might not seem like much in the context of multi trillion-dollar budgets. But it marks a significant ideological break from longstanding aversion to government involvement in anything remotely approximating national industrial policy (which often involves the familiar complaints that the U.S. government shouldn’t be in the business of picking winners and losers).

Furthermore, as Willie Shih, Professor at Harvard Business School argues, $25bn does in fact represent a significant bet on a sectoral specific policy and for good reasons:

With so many pressing needs in the country, this seems like a lot of money directed at a single industry. Yet semiconductors are a platform technology, and are used as a base for so much of the modern world. More than just iPhones, computers, and Zoom calls, semiconductors are used pervasively in entertainment, transportation and logistics, consumer goods, and virtually all manner of services. There are typically more than one hundred microcontroller chips in a modern automobile, and an airplane couldn’t get off the ground without them these days. The global pandemic has called attention to how dependent the U.S. is on distant manufacturing sites for so many of these chips, and how this is a glaring strategic vulnerability for the defense industrial base.

Shih makes a good case as to why semiconductors specifically make a good first step for American reindustrialization. The spin-off effects from this “platform technology” are considerable, both because of the economic multiplier effect, and also on the grounds of national security (the latter likely explains some of the newfound enthusiasm of the GOP for more government activism in economic policymaking).

As for the canard that governments don’t do a good job at picking winners vs losers, this is not borne out remotely by historical experience. In the US, the country’s “government-funded railroad boom of the late 19th century made possible the burgeoning Pacific cities and the agricultural boomtowns of the Wild West while the demand for rails provided a market to fuel the explosion of steel mills using the groundbreaking Bessemer process”, according to Ben Landau-Taylor and Oberon Dixon-Luinenberg

More recent examples abound in East Asian: Japan, Korea, Taiwan, and China, all providing excellent illustrations of countries that have experienced quantum leaps in living standards and growth via targeted sectoral industrial policy. They have done this successfully, not so much by operating in opposition to the markets, so much as using the market as a feedback mechanism in order to adduce likely areas for future growth, and then using that cumulative information to transfer state resources away from unproductive toward productive uses. In the case of South Korea, for example, this took the form of conglomerates such as Samsung starting in basic industries such as agriculture and textiles in the 1960s, rapidly progressing via government direction to more advanced industries, such cell phones, computers, and semiconductors, where it remains among the global leaders today. Likewise, the extraordinary growth of China over the last 40 years illustrates that governments can successfully impart directional thrust to the economy in line with an exercise of foresight about the economy’s future growth.

Even today, Asian governments from Japan to Vietnam continue to be intensely involved in technology acquisition and in driving enterprises, small, medium, and large, to upgrade their products and processes, and in mediating the integration with the international economy. While much of the regulation and the assistance is camouflaged on “national security grounds” to make the policy mix look WTO-compatible, the post-COVID-19 environment will almost certainly catalyze additional moves in this direction across the globe. There is little reason to embrace American exceptionalism here.

The relative power of the U.S. has diminished over the past few decades, although it has by no means reached levels of decline comparable to the United Kingdom in the post WW2 period. On the other hand, the quality of American jobs has been deteriorating for decades due to the changed composition of the employment base, in a country that has steadily shipped manufacturing capability offshore and become a hollow industrial shell of its former self in the process.

The United States was once synonymous with “can-do” manufacturing in automobiles, machine tools and computers. It now looks more like a serf economy that seems to do little more than “provide luxury services to the urban oligarchs, through their jobs as restaurant workers, nannies, health aides and apartment and hotel staff”, in the words of Michael Lind. That’s more than impressionistic. According to The U.S. Private Sector Job Quality Index prepared by Cornell University, since 1990, over 60 percent of all new paid and non-supervisory (P&NS) jobs created have been low-wage, low-hour roles, as opposed to higher quality goods-producing positions (this also helps to explain the relative precariousness of US employment in the current pandemically-induced environment relative to a country such as Germany, which has retained a vibrant manufacturing sector that was able to sustain production throughout the worst of the crisis).

There is no reason to expect a reversal of these trends, absent more initiatives such as the one recently introduced by Senator Cotton. The American state played a major role in creating the technological platforms that created the foundations for the country’s prosperity. Understanding this fact will enable this welcome piece of legislation to mark a decisive, but necessary, first step toward U.S. economic revival.

Recommended Reading

The Compass and the Territory

No particular worldview or ideology is necessary to see the reality of our political situation today. Due to the reshaping of our psychological and social environment by digital technology–a process laid bare by the unfolding coronavirus pandemic–our “map” of America is now out of date.

Is There a Case for Principled Populism From the GOP?

“Populism” is a term that since the modern era has been generally trotted out to mean a political attitude that reflects widespread anger and resentment against powerful elites, while among stenographers for the power class, populism has been reflexively trotted out to warn against the passions and wants of the mob.

Republicans Split on Major China Bill, as Legislation Barrels Toward Passage

As the Senate takes up consideration of the CHIPS Act, American Compass’s work is leading the industrial policy debate.