RECOMMENDED READING

In popular parlance an “apocalypse” means an epic disaster. As a simple transliteration of Greek (apocalypsis) the literal meaning is more pedestrian: “uncovering,” or to use a fancier word, “revelation.” But one understands the popular sense, for it is often unsettling (or worse) when the true nature of things is revealed. This is the case in last book of the New Testament, which bears the name Apocalypse.

The Trump phenomenon—his ability to gain the loyalty of core Republican voters, his defeat of Hillary Clinton, the endless uproar during his years in the White House, and the coalition of voters that almost gave him a second term—has been apocalyptic. To this day, our political establishment regards his impact as a disaster. And rightly so, for Trump has revealed unsettling truths about twenty-first-century America that most would prefer to remain covered up and hidden.

One could say that Trump exposed discontent. But this is not sufficiently precise. Beginning in the 1960s, our political culture has organized itself around discontent: black discontent over discrimination that exploded in urban riots, female anger over exclusion, and gay rebellion against stigma. This kind of discontent—anger over exclusion—has become so fundamental that it spawns industries (diversity consultants!) and sets the currency for political spoils as other groups clamor for victim status.

Trump revealed a different kind of anger, one based in feelings of betrayal, not exclusion. His 2016 campaign slogan, “Make America Great Again,” implies betrayal. How did it happen that we stopped being “great,” if not because our leaders misled and failed us?

Trump could be explicit. In the 2016 Republican primary debates, he said George W. Bush “lied” about weapons of mass destruction and got us into a futile war. His charge of “fake news” appealed to people’s sense that they were being lied to. Talk of “bad trade deals” implied that the country was led by people either too stupid or too corrupt to serve the interests of ordinary citizens.

Readers of “The Commons” are sophisticated enough to translate campaign rhetoric into more sober economic and cultural analysis. We can see that, yes, working class Americans were betrayed by globalization and financialization, which was sold to them as a win-win that was in any case “inevitable.” We can recognize that both parties avoided reform of immigration policy for good political reasons—but at the expense of working class wages and the cultural stability of lower-income communities. We know that the policy responses to financial crisis of 2008 ended up enriching those with capital assets, as are policy responses to the current pandemic. We acknowledge that the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan were shipwrecked by the ideological hubris of our ruling class.

Betrayal requires intent, and, again, readers of this forum are not simple-minded. We understand that Robert Rubin, Dick Cheney, Hank Paulson, and others did not aim to sell out the country. But things did go sour under their watch. And it’s not a stretch for John Q. Public in Youngstown, Ohio to say our leadership class “betrayed” him, if we take that term in a broad, non-moralistic sense.

Therein rests the foreboding so many feel about the last four years. Those of us writing columns such as this one are members of the leadership class. It’s unsettling for someone to say we f—d up in a big way. And it’s quite frightening when a political entrepreneur gives many millions the voice to say it.

The apocalyptic effect of Trump’s tenure on the public stage is compounded by our political culture. As I noted above, over the last 50 years we’ve developed an elaborate cultural machine for processing anger over exclusion. That’s why BLM protests left our establishment unperturbed. But we have no mechanisms for dealing with anger over betrayal. That’s why our political establishment came unhinged in 2016, fearful that “fascism” or some other vampire from the 1930s will rise from the dead.

Commentators who draw analogies between Hitler and Trump (and they are legion) are misguided, not because no analogies exist, but because they are historically ill informed. Being sold out, betrayed, lied to, misled—these have been perennial themes of rightwing populism. In the 1930s, many nations were in the grip of this kind of populism, including our own. “The stab in the back” was fundamental theme of Hitler’s populism after World War II. Franklin Roosevelt’s played similar tunes. He claimed to be the voice of the common man, whom the rich and powerful had shamelessly “forgotten,” which is to say betrayed.

In that ugly decade, political turmoil arose as society’s “center” rebelled against what it perceived to be its internal enemies. The “center” idolized its champions, whose rhetoric lashed and punished those deemed to have betrayed their country. Fr. Coughlin could sound ugly notes not too far removed from Hitler’s. Roosevelt had his own populist rhetoric as well. He often rallied his supporters by demonizing the “economic royalists” who imposed “a new despotism” that was “wrapped in robes of legal sanction.” FDR condemned the princes of industry and finance as traitors to America’s founding principles.

The Trump years were apocalyptic. They uncovered the destabilizing implications of today’s elite-sponsored multiculturalism, which demonizes the “center” and praises “marginality.” His explosion onto the national scene prompted the New York Times to denounce America’s founding principles as racist. Corporate America responded by further contorting itself to affirm “diversity.”

Twenty-first-century American liberals are unable to acknowledge anger over betrayal, much less address it. They are satisfied to dismiss it as nothing more than xenophobia and racism. And what of Roosevelt’s common man? In the diversity wonderland of “creativity” and “innovation,” he’s a mono-cultural liability, not an asset.

American conservatives have a similar outlook, although it is usually framed in the language of Milton Friedman rather than that of diversity consultants. The upshot is the same: the “center” of American society has little standing.

I look back on the Trump apocalypse with foreboding. Roosevelt worked his magic during his long grip on power. As America’s greatest demagogue, he restored social trust between the leaders and the led (very much aided by a global war in this crucial work of political healing). Is such a person possible today? Our circumstances, imbued with fears of exclusion and prone to seeing fascists behind every populist tree, seem much less auspicious.

Recommended Reading

The Future of the Biden and Trump Coalitions

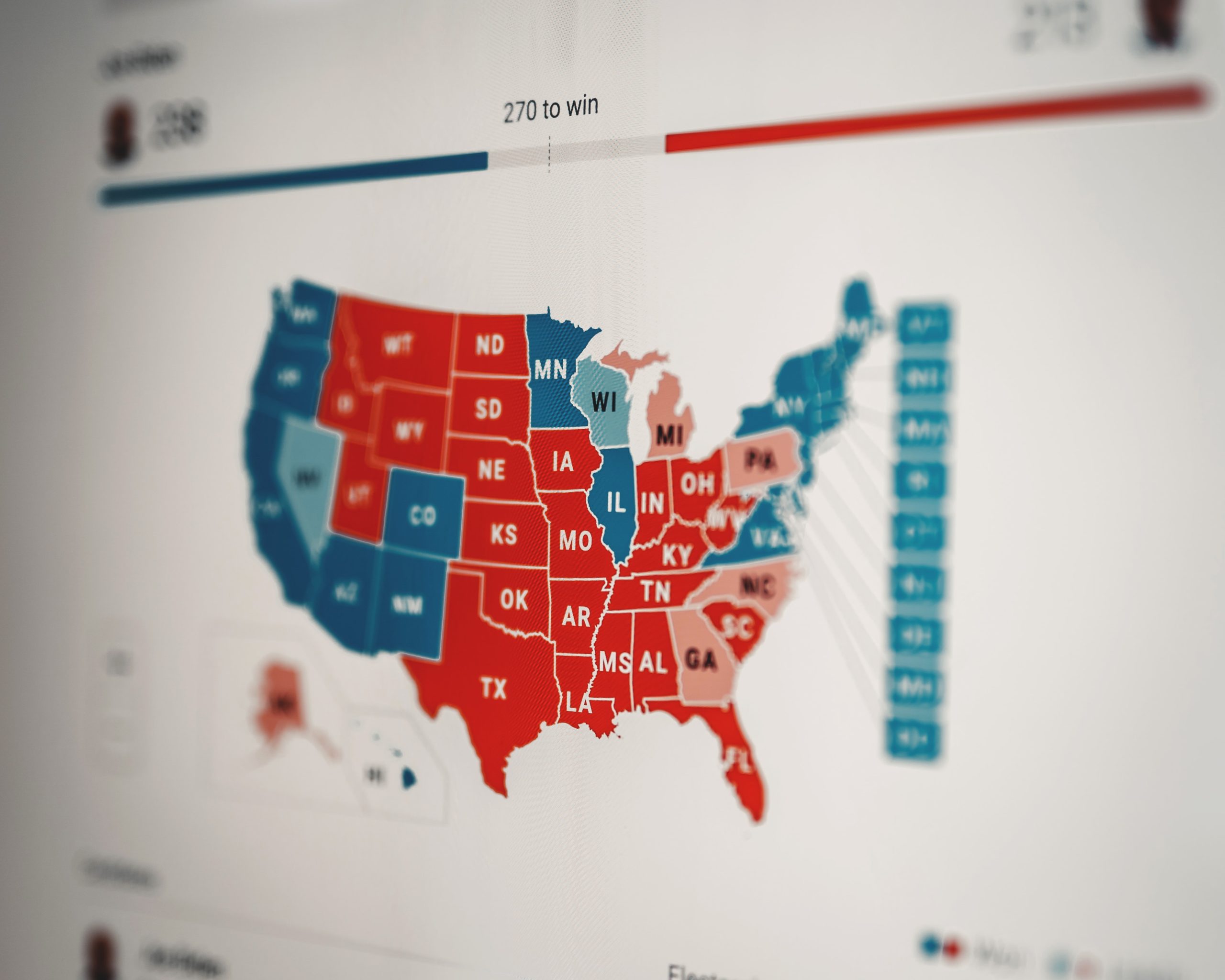

While Joe Biden will be the 46th President of the United States and Donald Trump will join the small club of incumbents who could not get re-elected, it’s fair to say that Biden’s triumph was not so overwhelming that it even begins to settle the question of which party will dominate the 2020s.

A New Coalition, if You Can Keep It

As the pundits, campaigns, and lawyers continue to unpack this election, there are a few things we know for certain.

Trump Lost the Race. But Republicans Know It’s Still His Party.

Jeremy Peters highlights American Compass as a leader in building a post-Trump conservative movement by bringing together Capitol Hill staff and policy experts to debate the successes and failures of the past four years.