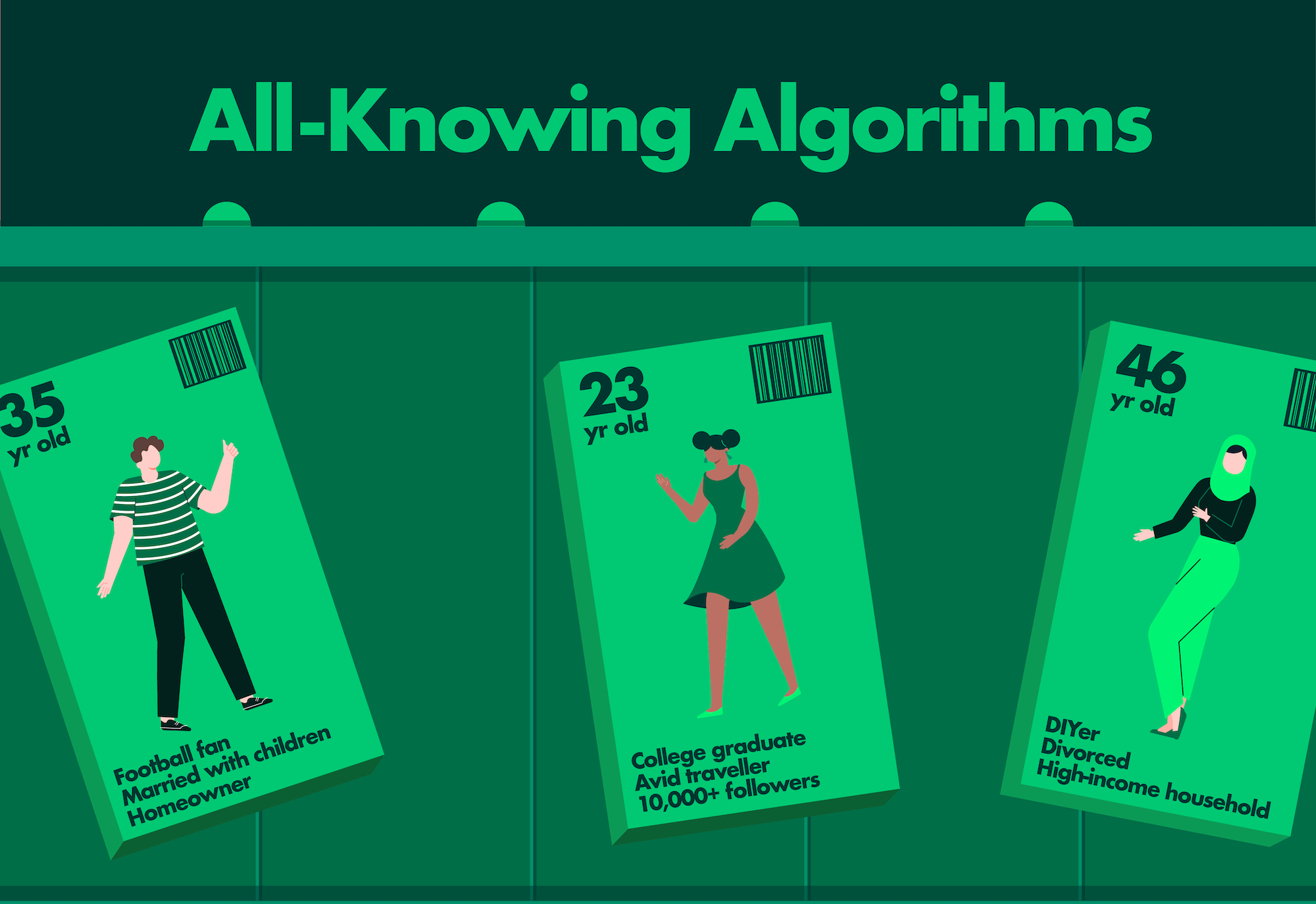

What happens to personal data as the digital age deepens their quality, widens their availability, and creates new uses for them? Alec Stapp (Progressive Policy Institute) and Wells King (American Compass) discuss the implications of “All-Knowing Algorithms” with Oren Cass.

Transcript

Oren Cass: Alec, Wells, thank you guys so much for joining for this conversation. The topic today is data and privacy, and I think we should really just talk first about what we see as the issue, if anything, in that realm. So, Alec, I guess, would, would love to start with you? When you think about these issues, what do you see if anything that gives you pause or cause for concern that people should be worried about or that policymakers should potentially be thinking about?

Alec Stapp: Yeah. Thanks, Oren, for having me, and glad to be here with you, Wells. The first thing I think about when it comes to privacy are our market failures and how policymakers will step in to correct or remedy those market failures. So, a thing a lot of people think about often is, “Why does my data seems to be worth a little,” or, “I get these potentially great free services where companies pay me for my data.” People look at big tech companies worth hundreds of billions or even trillions of dollars and say, “Why are these companies worth so much money, yet I don’t get paid for data I share with them?”

I think those are all lots of fair questions that need to be answered that policymakers have every right to investigate. So, at first blush, I think one of the things I think about is the negative externalities of sharing personal data. So, when I share information about myself, oftentimes that includes other people or has implications for other people. If data I share can be linked to them, that means that it directly implicates their personal privacy or is it can be in so far as if I upload a photo. I am in my photo, but you’re in the photo as well. Right? I’ve shared information about you, your location, or who you affiliate with within that photo.

Email is the same way. The record of my emails, those are messages between two or more people. So, every time you share the text of an email or the record of an email, that’s implicating other people. And this is probably the default. Most information is like this. So, if we ask ourselves, “Why is data worth so little on the open market, and why do tech companies not feel the need to compensate users more than they currently do,” I think one thing you can look at is, okay, there’s been a market failure where these negative externalities of your data are being shared by others all the time. So that reduces your own incentive to protect your own data.

Alec Stapp: There’s a paper by Daron Acemoglu and other economists looking at this, and the question then is like, how do you remedy these things? So, limits on third-party data brokers can help us this problem, where if you limit how much data people can share without your consent or without your knowledge behind the scenes. These are companies you’ve never heard of. Right? This is not Google and Facebook. This is Axiom and other third-party data brokers. If you put limits on them, then that raises the value of protecting your own data, and you might get more compensation for it. I think those are some of the potential solutions people should be looking at.

In their paper, they also have one about data intermediaries. So, is there a potential solution you could do? Let’s say maybe a governmental or non-governmental solution, but could you give it to a third party who then transforms your data or pools it with others to protect your own privacy and then shares it with a company with your consent? You can strip out the data about other people and just isolate it to you, and then you hand it to the companies, then you’re solving the externality problem. So, I’m open to ideas like that, either they’re from policymakers or from other individuals.

Oren Cass: That’s really interesting. I think the focus on market failures gives nice concrete contours to the definition of the problem and then the kinds of solutions we’d look for. Wells, I guess, thinking about your writing on this, your focus is a little different. How do you describe the problem that we’re looking at and that we have to think about?

Wells King: Well thank you for the question, and Alec it’s great to be in a discussion with you about this. For me, the real challenge is just that the context of the real world that we have to govern our privacy doesn’t translate well to the digital realm. We understand the information about us that we control and that we share with others to be contextual. We allow some folks to gather their data from us, for instance, like a GPS that tracks our location to be able to provide some navigation for us. We consent to that, but we may not so much consent to or even be aware of the other applications that may be able to gather our data.

So, the kinds of frameworks that we have that govern the transfer of personal information and that governed privacy and what counts as both public and private in the real world, don’t translate particularly well to a digital context. In part, that’s because of a lack of intelligibility. Users, I don’t think, have the best sense for just how much data is being collected and then what those data are being used for. We have these service agreements where users effectively consent to the collection of their data, but as I think we all know from experience, users really don’t know and really don’t read through those things as thoroughly as they should.

So, they don’t quite appreciate the extent to which their data are being collected, that they’re being aggregated, that they’re being sold, and they’re also being used to study them and their behaviors. So, for me, what this becomes is not just a question of our informational privacy, our ability to control the data and information about ourselves, but really about more like decisional privacy and the freedom of choice and being able to make our choices free of interference. When we allow companies to collect data on us to use it, it’s not so much that we’re surrendering a valuable piece of property, but rather that we’re allowing them to manipulate the environments in which we make choices and decisions every day.

It creates an excess of nudges that shape the digital environments that we operate in and the choices that we make, and this is a feature of the web and of these tech firms that users don’t quite fully appreciate. So, the implication is really not so much, again, to market failure or to the value of data that users aren’t necessarily receiving, but really about the ultimate implications for individual freedom and the ability to be able to make choices where you understand and appreciate the context in which the choice is being made and which it’s also free of interference of outside actors.

Oren Cass: So what about that, Alec? It’s an interesting point that the discussion of market failures almost assumes we’re starting from a typical market where I’ve got things I’m buying or selling, you’ve got things you’re buying and selling. Does that feel like an accurate description of what is going on in the data world, or do you think that Wells has a point about some of the ways in which that’s not even how people are interacting with this realm?

Alec Stapp: Yeah. I think it’s a little bit of both. That’s a great way of framing the question. So, I’ll start with one, I think, Wells’s point about individual freedom and whether under the current paradigm or environment people are even making choices of their own free will or where they’re achieving the ends they want to achieve. I think this is kind of probably one of the… I’m sure we’ll get to a few of our fundamental disagreements where they’re just value judgments or disagreements on what the world should look like. But I think one of the ways I disagree with Wells is to say that not necessarily that the data markets are currently perfect. I mentioned there are lots of market failures and ways to improve them, but at a basic level, people should have the freedom to trade personal information about themselves for access to services or for other monetary value, or for other gains. And I think that to me is the true freedom to recognize that people should have the choice to allow that information to be used about themselves, because there are just huge gains, both at a private level and a social level to sharing data in that sense. Products become better, they come more personalized, more customized. So it’s no surprise to me that users often want to share data about themselves to get a better service. And then that has a direct effect of like if you were not up to allow any kind of data sharing in the future and like have more blanket bans on it, then you get a situation where people have to pay for things out of pocket.

I don’t think it would actually change people’s preferences that much, it would just raise costs. So for example, right now currently, I get bombarded with YouTube Premium ads more than any other type of ad I’ve seen in the entire world. Like every day, YouTube is like, “For $9.99, would you like to sign up for YouTube Premium and not have to watch ads on YouTube anymore?” And like, yeah, the ads are kind of annoying, but I’d rather not pay for it. And so they just keep bombarding me with it. And that’s what the world would look like if you weren’t allowed to use personalized data for advertising or have any kind of ad-supported model that relies on data.

And so you will just hear things more of like, “Would I watch YouTube less? I don’t know, probably not, because I would still probably pay for it because I like having access to this huge volume of content.” So I think that’s like one area where Wells and I disagree is I think there’s disappointment among your team with the choices people are making and you want to nudge them the other direction, but I don’t think that the current choices are unnatural in any sense.

Oren Cass: Wow. So Alec says you’re the one doing the nudging, Wells?

Wells King: Well, so really my issue is not so much with the decisions that users are making, them opting into these things. We know that users are willing to surrender their data all the time for ease of convenience with particular services. I think the problems arise, one, when those data are then transferred to companies that we’ve never even agreed to or even heard of. And then also when these data are aggregated and studied with AI, artificial intelligence, advanced analytics that really allows a degree of behavioral prediction, which combined with the plasticity of digital interfaces really does, I think, give these corporations a degree of control that’s not merely just a targeted ad for folks that happen to have a dog for dog food or for folks that may want to go into YouTube for YouTube, but have the potential for real consequence in terms of not really the information that they see, but also decisions that they may have no control of.

For instance, if they’re going to opt in to certain insurance benefits, it’s been used for tracking down bounties and bail. The types of decisions that these data are used for users often aren’t aware of. And so when we consent to allow GPS to track our location or when we allow Facebook to know our age and certain sort of likes and preferences we have for the purposes of advertising, that’s one thing in terms of easing the service. But when it’s used to make decisions we may not be aware of and that have real consequences for our lives and when it’s also used to be able to, I think, predict our behavior, and in some cases know ourselves sometimes better than we know ourselves, when they’re able to anticipate the kinds of likes and things we may be interested going forward, that’s where I see a real implication for individual freedom and choice.

Alec Stapp: Well, I’d love to follow up on that, because I think you put a lot in there that I think can kind of help us tease out where we agree and where we disagree. To start going backwards, the last thing you mentioned, that’s one of those things where I think people will react differently. It’s like when you describe a company or a product or service knowing me better than I know myself, I don’t immediately have a negative reaction to that. I think if they could offer me a product I was unaware of that would benefit me in a great deal on a day-to-day basis like at a good price, I might want to hear about that offer, even if I didn’t know myself well enough to go look for it. So I’m not immediately repulsed by that idea, which is I think people will react differently to how much companies know about them.

But I’m really glad you mentioned aggregated versus dis-aggregated data, because I think that that is probably, again, another basic disagreement we have. So on the disaggregated data, like personalized data being sold behind the scenes and things like shadowy data broker markets, like there are profiles about you as a person, like 5,000 attributes about you that can be bought and sold for pennies on the dollar or whatever. That’s concerning to me and that’s something that needs more regulation and limits on, like if you didn’t consent to these profiles being handed around behind the scenes, I could definitely be open to that. I’m also open to things like in the privacy debate, these are known as the purpose limitation principle of limits on what companies can do with data if they haven’t asked for permission or it’s not like have a direct connection to the end result of the application or service that is using the data.

So that I think we have a bit of overlap or agreement. Where we have a lot more disagreement would be on the dangers of aggregated datasets. I just am not persuaded that that’s actually problematic. I think there are huge benefits to doing so. So in terms of violating people’s privacy, once you aggregate it up to a population level, whether that’s a national population or even subgroups of that, it’s really hard for me to see the potential harms and their obvious gains. So just to give one concrete example, Pfizer, for their COVID vaccine, when they were deciding which countries to give early contracts to, they obviously considered price, who’s willing to pay the most? But another thing Pfizer really wanted was data about how the population was doing with the vaccine, like side effects, effectiveness, just like follow-up population-level data.

They didn’t need any individual-level data. And the Prime Minister of Israel, Netanyahu consented to all those things and said, “Yes, if you work with us, the National Health Agency in Israel will share the population-level data with you, the aggregated data in addition to paying a higher price.” And so that’s why Israel vaccinated so early is because they were going to make this kind of deal. And in a sense trade some data for a concrete public health benefit. But on the contrary, European Union also was not willing to pay a high price and they weren’t willing to sacrifice privacy at that level at the aggregated level. And lo and behold, Europe is falling behind in the vaccination campaign. And so I think that’s a case where really clutching closely like these super-strong interest and privacy and not trading away for anything, especially at the aggregated level can leave you a lot worse off in the long run.

Wells King: Yeah, so perhaps I should clarify, I guess, kind of the type of aggregation that I mean. So there’s the one type which is an aggregation at say the level of like a demography. So you want to gather data on the way that consumers behave in Cincinnati, Ohio, or the way that people who watch an NFL game are going to behave, the types of preferences they may want. That kind of aggregated data, which we have all the time, we track consumer behavior in the market today, even before sort of the advent of personal computers, we do surveys. These types of things where it’s essentially anonymized. I have no real worry about that really as much. I mean, and that enables the kind of contextual advertising, not the kind of targeted behavioral kind that I’m really worried about. And so the type of aggregation that I’m worried about is collecting data from multiple sources about an individual user. So not only being able to collect your location, but say your political attitudes, the types of stores and restaurants you tend to frequent, the type of entertainment you watch, your medical records, your heart rate, if you work out or not. The aggregation of personal data points into individual profiles is really what concerns me. It’s less about trying to get a sense for how consumers or users more broadly are behaving and responding to things. It really is about trying to understand an individual through multiple types of data points that are aggregated into one particular profile.

Alec Stapp: That’s helpful. And if I could ask you a follow-up question, just to help tease this out a little more. And this is something actually I still do not have a firm position on, but I’m open-minded about. What would you think of an intermediary solution like what Google is doing with FLOC, the Federated Learning of Cohorts? Obviously, I’m sure you’re aware that we’re moving away from cookie-based tracking in the online world for targeted advertising. So the individualized cookies, there are alternative models that encrypt those cookies and maintain unique identifiers to the individual level that Google has not endorsed and does not want to pursue.

And so, Google’s substitute, moving away from individuals, is like what we’re going to do is collect a bunch of data about you, a lot of those personal attributes that you’re discussing, collect it locally on your device if it’s mobile advertising, and then model your behavior locally on the device so it creates a model of that, and then the federated learning part is where then a higher-level model of everybody’s data, you get placed into a cohort based on your unique behavior, like people who are similar to you. And then that is sent up to Google, but none of your individual data ever leaves the device. It’s just that you’ve been placed into a cohort, so Google knows that you are kind of like these other people along certain dimensions.

And then it shows you ads that are relevant. Google claims that it’s like 98% as effective in terms of advertising effectiveness. I don’t know if that’s true or not, but I’d be curious to just hear your take on that of this intermediary level where it’s not just broad demographics, but it’s not individualized either.

Wells King: Right. So I like that from one standpoint, which is the security of data and the security of individual data. I think trying to preserve as much as possible some degree of anonymity in accessible and tradable data is really important for ensuring that people … Well, frankly, just that the information is not used against them for all kinds of purposes.

The one type of worry though that I have with often these types of privately developed and generated solutions is just their intelligibility. I think oftentimes, it is very, very difficult to explain the types of systems and algorithms that use and manipulate and collect user data. Oftentimes, I think they create a kind of a black box, right, where it’s tough to actually know what’s taking place. And so you don’t really know what you’re consenting or agreeing to. So to the extent that we could, I think, better explain what users would be opting into with these types of private solutions, I definitely would be interested in and would want to explore that a little bit further.

And I also think that kind of blockchain technology, which it sounds like this uses in part, is another way of ensuring that sort of the integrity of data are maintained and that their security is maintained. But I do think these kinds of basic threats to individual freedom of choice could still be there if users don’t exactly know the type of service that they’re buying into or that’s being applied to them.

Oren Cass: Yeah. So I want to pick up on something you’ve both mentioned in different contexts. Alec, you mentioned kind of the purpose limiting principle, which I think is a really interesting way of talking about this issue. And then, Wells, you described the concern of people’s data being used against them, which I think is a similar concept in a sense that that is, it seems like we worry less about the sharing of data when it is genuinely for the purpose that the user either is or we assume would consent to use the data. So for instance, we don’t mind when the GPS app tracks you. Excuse me. We do potentially get frustrated when the shopping app tracks your location.

And it’s really interesting to think about the disaggregated versus aggregated structure and say, look, even disaggregated data, if it never comes back to me again, like if the National Institute of Health wants to collect and secure a whole bunch of personalized data for its research, but it never affects how anybody treats me, then I’m probably less concerned. It’s the, hopefully, I won’t have anyone coming after me for skipping on bail, but if they do, it’s that or the extent to which advertising is informing you about a product, but really sort of aggressively upselling you or trying to prompt a purchase.

I guess the other example that I just find so striking and hopefully useful is the example of colleges using email open rates in their admissions decisions. That is if they send out blast emails, they can tell who opened them. And they then know the people who opened the emails are more interested and more likely to accept, and it moves you up the probability of being admitted. And it’s an interesting question on a bunch of levels. Should I, as a prospective applicant, know that emails that arrive in my inbox can be tracked that way? Should I have some option to consent to whether they are? Or regardless of whether I consent, should we need to say, “You know what, colleges, that’s not really how to go about your admissions decisions.” I don’t know. So Alec, you raised kind of the purpose limiting concept. How would you apply it in practice just in different situations where you see it could be useful?

Alec Stapp: Yeah. So on purpose limitation, I think this is where we can, again, get into the distinction between first-party and third-party data, or like data brokers versus getting platforms that everyone uses. And I think this is where it’s really interesting to me that we have these conversations. The reason we have this conversation is because big tech is in the news and it’s what everybody talks about and cares about. But then very quickly it goes in a reasonable conversation like this examples from insurance markets get brought up, credit markets, criminal justice, and I’m all on board for that because I agree. Those are more sensitive types of data that require a higher burden of proof in terms of what you’re doing with it, transparency, right to appeal, et cetera, et cetera. Which is very interesting when the conversation starts in one place and ends up in another.

And so, one, I think understanding that our current regulatory environment acknowledges this to some extent. So in a sense of like, what data is allowed to be used against you, quote-unquote, for a credit decision if you want to buy a house, get a loan for a car, or something like that? Those are already highly regulated decisions that go through licensed regulated credit bureaus with tight controls on what data points they’re allowed to consider or not. These algorithms are audited. And it’d be like insurance. You’ve mentioned health insurance markets. Again, there’s statutory language about what they are and are not allowed to consider there. And so I think those are good safeguards because, again, these are very highly sensitive pieces of data. And that doesn’t mean we don’t need a comprehensive federal privacy law that covers the gaps in the system for lessons and types of data that don’t have as many productions. But I think that’s the key thing I would say is one, you need kind of a multi-tiered system of recognizing that the risk to some types of data sharing is much different than others. I just think the risks are lower for those kinds of targeted advertising-type questions. And then, therefore, the rules around them need to be different as well. And so that I think purpose limitations could go hand-in-hand with that of having a stricter purpose limitation on more sensitive kinds of data.

Oren Cass: And to what extent would that satisfy your concerns, Wells? Or do you want to get back to big tech?

Wells King: No. That kind of purpose limitation, I think, maps onto, I think, just sort of common-sense understandings of what counts as privacy and what doesn’t. The way we treat privacy and the types of information that we devolve to certain people in certain institutions is incredibly context-dependent. And this is the reason why we have particular laws that govern health information, financial information. And I think trying as best as possible to apply those types of frameworks to different digital contexts is exactly the appropriate way to do it. Trying, I think, to enshrine an inalienable right to digital privacy is the wrong way to go, in part because it doesn’t reflect the actual understanding, common sense understanding, but also the behaviors of digital users.

But what we need to make sure that we do is not only sort of look context by context and purpose by purpose what is appropriate and what’s not, but also, we need to do as much as possible to make sure that users are able to understand how data are used, both for and against them. Again, trying to make these systems as intelligible as possible, not only so that the users can truly freely consent to the services, but also so that they can hold them accountable; the algorithms that are developed, the types of decisions that businesses, institutions make with these data. I don’t just want it to be a federal agency or technocracy, that sort of thing, governs these things. I do want these to be, to a real extent, democratically accountable. And so, yes, we do, I think, need to approach these privacy questions online with an eye toward both the particular context and particular purpose of the data, but we have to make sure, too, that the systems are as intelligible and understandable to the public as possible.

Oren Cass: Yeah. That’s well put. I think, last question, Alec, I want to send back your way, and it comes back to the big tech side of things a little bit, which is that one concern Wells has raised is you have these sort of big tech companies and platforms that are so integral to participation in modern society in a sense, and it can feel like consenting to their terms is sort of the price of admission. And I think you point out, yes, you can stay off them. You can use DuckDuckGo, you can jailbreak your iPhone. The sophisticated user can, but the typical user, yes, all things equal, they like these services and they’ll give up their data to use them. But to be honest, if that’s not how they felt, it’s not clear what they could do about it besides moving to a cabin. And so I’m curious to what extent do you see, more to Wells’s point about democratization, intelligibility, and control, do you see a need to ensure that users have some level of control just almost by right where you have these kinds of technologies becoming so pervasive, or if nothing else, does that just sort of become unwieldy and start to make them less useful than we’d like them to be?

Alec Stapp: Yeah. I think probably a lot hinges on how we define control over your data in that context. And maybe I’ll disagree from the other side with Wells on the legibility or kind of informed consent model though, because I basically agree with what you said earlier about no one reads the privacy policies. People don’t time for that. It’s rational not to read the privacy policies because you’d spend all day, you’d spend your whole life actually reading if you actually read the terms of service for every single free product or service you used. And so then the question is, we need policymakers in DC and around the world to set the rules of the road and be the ones making these kinds of governance decisions about what they can and cannot do with data.

And I think a key distinction we’ve mentioned a few times here but I’m just going to reiterate it again, is when data leaves one company, either authorized or unauthorized, I think that’s a much different situation than data held within a company. So authorized obviously being buying and selling, that there should be much stricter controls on when data about you is sold to another company; you should have more of a say in that. And then in terms of unauthorized data breaches, there should be obviously harsh penalties to incentivize companies to protect their data more closely because it’s a pretty classic market failure to me where companies know that in the case of a data breach, they wouldn’t report it otherwise because they know that if you get your identity stolen or suffer some kind of concrete harm to having your privacy violated, it’s so hard to trace it back to, oh, five years ago I had an account on LinkedIn and LinkedIn got hacked, and that’s how I know and I can trace it and I could sue Microsoft who owns LinkedIn and I could get some kind of compensation.

Too many transactions cost, too many information costs to actually sussing that all out. And so I think that data breaches are one clear market failure. That’s why all 50 states have their own data breach notification law. Why don’t we have a federal one? Why don’t we harmonize those and have stricter penalties for companies that suffer data breaches through not following best practices? I think those kinds of principles could take the decisions out of the hands of companies and put them back in policymakers’ hands, which I think is the appropriate thing to do there.

Oren Cass: All right. Well, I think we’ll leave it there. Certainly, plenty of work for policymakers to do, and hopefully they will call up Alec and Wells when they are ready to take that on. Wells King, Alec Stapp, thank you guys both so much for this conversation and for your work on the project.

Alec Stapp: Thanks, Oren. Thanks, Wells.

Wells King: Thanks.