Responsive Politics

Defining success as achievement of the outcomes that people value most

Policymakers have depended in recent decades on an economic model that uses “consumer welfare” as its only measuring stick. In this way of thinking, policies are successful if they increase how much we can all consume. Whether income is earned through paychecks or redistributed through government transfers, whether communities thrive or collapse, whether inequality rises, whether families form, none of that counts. If everyone has more stuff, the market has delivered.

As a result, both economists and politicians ignored Americans’ growing frustration with an economy that offered big flat-screen TVs at door-busting prices, but shipped manufacturing jobs overseas. According to the economic theory, that was a great trade. Likewise, using government checks to make up for stagnating paychecks was widely celebrated as a solution, though most Americans saw it as a problem.

This is why economics needs politics. The market has amazing power to coordinate the actions of millions of individuals through price signals and freely chosen transactions. But the market has no power to recognize, let alone provide for, the many needs that are not reflected in price signals, even when they are more important to people’s lives and require greater coordination and cooperation.

No matter how much people want to see investment, growth, and job creation spread widely across the country, markets will concentrate it in narrow geographies or send it overseas if that provides investors the greatest return. No matter how much people care about forming and raising strong families in thriving communities, markets will value their efforts and the results at roughly zero. Identifying such priorities, and establishing public policies that force market actors to take account of them, is a task that only politics can complete.

At American Compass, we work to identify the values and priorities that Americans hold dear but markets ignore, and to ensure that the nation’s politics and policymakers do not ignore them as well.

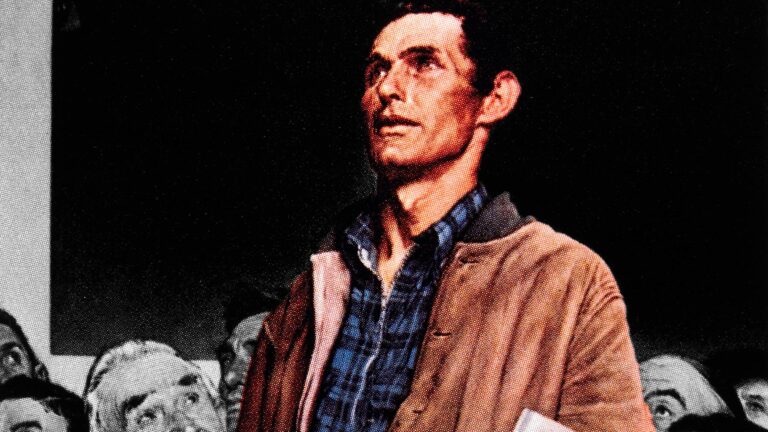

We do this through a variety of projects that aim to bring forward perspectives missing from national policy debates. For example, The Edgerton Essays feature commentary from two dozen working-class Americans answering the question, “what do you wish policymakers knew about the challenges facing their families and communities?” Our in-depth surveys of thousands of Americans provide a novel view of their concerns and aspirations for their families and their careers. And our Atlas series highlights the data hiding in plain sight on the American experience and how it differs from the popular narrative.

For economic policy to succeed, policymakers must know what their constituents want them to accomplish. Economists have claimed to know people’s interests better than the people themselves, with disastrous results. Conservative economics accepts with humility that it can answer the question of “how,” but only after the nation has decided the “what.”