On the difficulty and importance of protecting the public square from the cult of expertise

RECOMMENDED READING

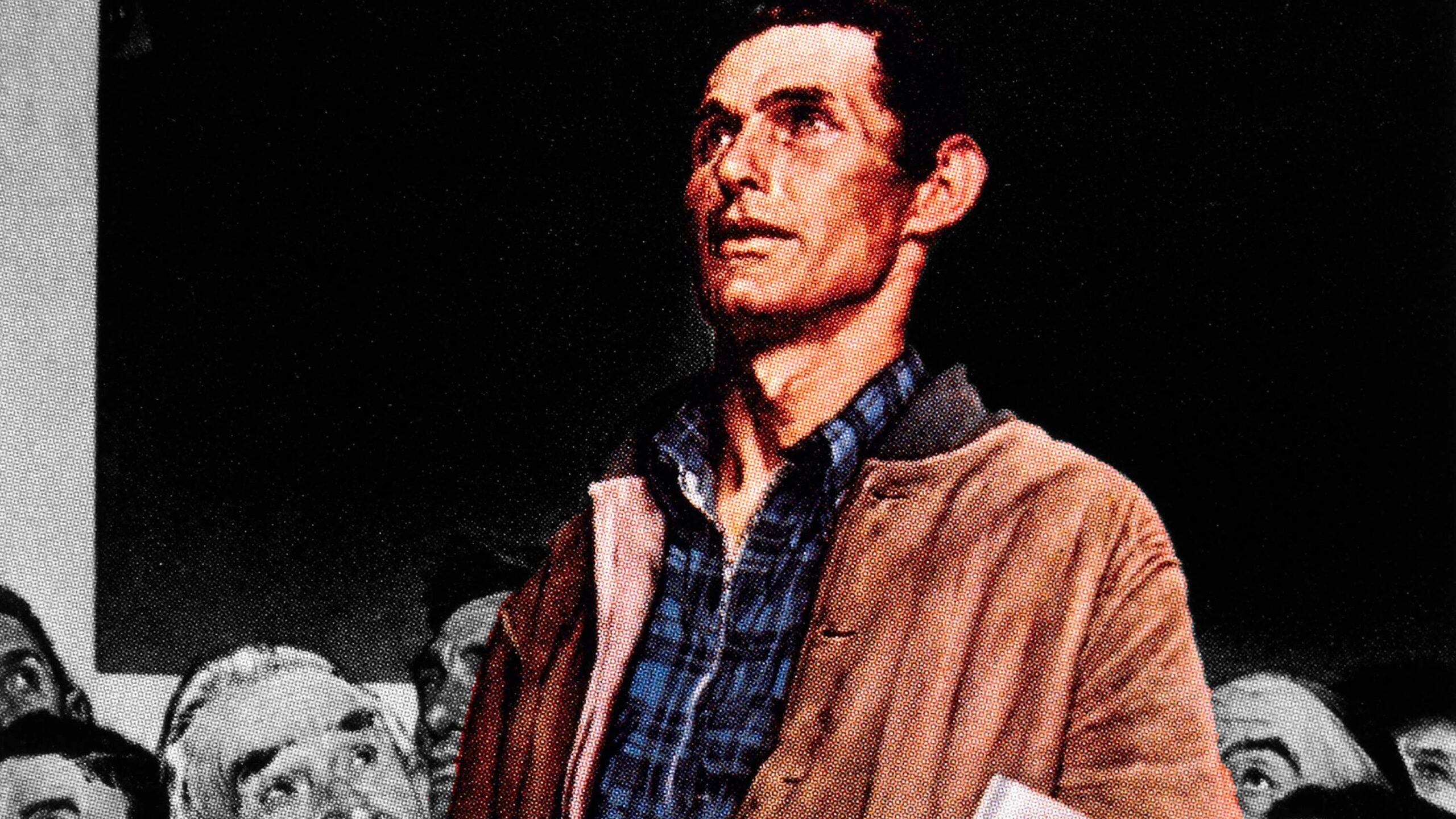

A few weeks before Donald Trump’s inauguration as President, the New Yorker published a cartoon depicting a mustached, mostly bald man, hand raised high, mouth open in a sort of improbable rhombus, tongue flapping wildly within, saying: “These smug pilots have lost touch with regular passengers like us. Who thinks I should fly the plane?” The tableau surely elicited many a self-satisfied chuckle from readers disgusted by the populist energy and establishment distrust that they perceived in Trump’s supporters.

But what exactly is the joke here? Citizens in a democracy are not akin to airline passengers, buckled quietly into their seats and powerless to affect change, their destinations and very lives placed in the hands of professionals guarded by a reinforced door up front. Even brief reflection reveals the cartoonist’s analogy to be comparing like to unlike.

That none of us thinks we know better than a plane’s captain, yet we often think we know better than experts in matters of politics, suggests differences between those domains. And it highlights a vexing problem for modern political discourse and deliberation: We need and value expertise, yet we have no foolproof means for qualifying it. To the contrary, our public square tends to amplify precisely those least worthy of our trust. How should we decide who counts as an expert, what topics their expertise properly addresses, and which claims deserve deference?

* * *

We all rely upon experts. When something hurts, we consult a doctor, unless it’s a toothache, in which case we go to a dentist. We trust plumbers, electricians, and roofers to build and repair our homes, and we prefer that our lawyers and accountants be properly accredited. Some people attain expertise through training, others through experience or talent. I defer to someone who’s lived in a city to tell me what to do when I visit, and to a colleague who’s studied a particular topic at length even though we have the same mastery of our field overall. A friend with good fashion sense is an invaluable aid in times of sartorial crisis.

“How are those without expertise to determine who has it?”

In all these cases, our reliance on expertise means suspending our own judgment and placing our trust in another—that is, giving deference. But we defer in different ways and for different reasons. The pilot we choose not to vote out of the cockpit has skill, what philosophers sometimes call “knowledge how.” We need the pilot to do something for us, but if all goes well we need not alter our own beliefs or behaviors on his say so. At the other extreme, a history teacher might do nothing but express claims, the philosopher’s “knowledge that,” which students are meant to adopt as their own beliefs. Within the medical profession, performing surgery is knowledge-how while diagnosing a headache and recommending two aspirin as the treatment is closer to knowledge-that.

But how are those without expertise to determine who has it? Generally, we leave that determination to each individual. A free society and the free market allow for widely differing judgments about who to trust about what, with credentialing mechanisms in place to facilitate signaling and legal consequences for outright fraud. Speculative bubbles notwithstanding, the market also helps to aggregate countless individual judgments in ways that yield socially valuable outcomes. Two New York City diners may have signs promising the “World’s Best Cup of Coffee,” but the one that actually has good coffee is more likely to be bustling on any given day and to thrive in the long run.

In the public square, we have historically placed our trust in a similar phenomenon, the wisdom of crowds. In the early 19th century, the Marquis de Condorcet codified the thesis that citizens who know less than experts can together generate a system that knows more. Condorcet’s Jury Theorem demonstrates a simple consequence of the law of large numbers: If voters are more likely to vote correctly than incorrectly and their votes are statistically independent of each other, then as the number of voters increases, the probability that voters get the right result approaches 100%. In large enough numbers, thinking for themselves, the vox populi will make the right decisions.

This rational populism has not been sitting well with the expert class, which finds democracy an inconvenient obstacle to technocratic rule. Thus the recent emphasis on “cognitive biases,” which treat the typical citizen as not only a non-expert himself, but also incapable of identifying the real experts or aggregating his opinions with other non-experts to achieve a reasoned result. There is confirmation bias, negativity bias, status quo bias, “tribalism,” and so on. Particularly en vogue are the “implicit biases” of identity and diagnoses of “racial resentment” and the “authoritarian personality”, which were used to explain the results of the 2016 election. Constructs like these provide the backdrop for expert dismissals of disfavored political views. Alongside the technically framed analyses of how people misprocess correct information comes an assumption that they are also cheaply programmable, easily gulled by puppeteer propagandists and “Fake News.”

Only the experts, then, can tell us who is truly an expert. Only someone untrustworthy would not trust them.

* * *

Obviously, we can do better than this morass of circular logic and Catch-22s. But before turning to the question of how a healthy democracy might engage expertise, it is worth enumerating the many problems of our status quo.

One such problem is that the expert critique of common sense and the crowd’s wisdom is wrong. Many claims of psychological bias have collapsed in the social sciences’ replication crisis, while others have been minimized or undermined by their narrow scope and unreliability. Repeated tests of implicit attitudes yield highly variant results and seem to have little predictive utility; the attitudes may simply accompany behavior rather than cause it. Where biases do exist, accuracy may dominate them in human perception, even when it comes to matters of identity. Psychologist Lee Jussim calls the well-replicated finding that we do quite well in this regard “stereotype accuracy.” As cognitive scientist Hugo Mercier shows in his book, Not Born Yesterday, demagogues tend merely to reflect popular consensus and rarely manage to shift it. Where widespread mistakes occur, they trace back not to snake-oil salesmen but to moments when common sense was misleading, or when people had little stake in whether their beliefs turned out to be true.

Ironically, the expert critique more effectively serves as a critique of experts. More so than the population, they appear susceptible to motivated reasoning and belief cascades. The replication crisis is a case in point, overturning dozens of seemingly established results, especially in social psychology, that claimed large effects on people’s behavior from deceptively small inputs. The findings that have succumbed range from bestselling fare like the “power pose” claimed to give women feelings of confidence and strength to storied research like the Stanford Prison Experiment. Incentives to find popular, important, statistically significant results seem frequently to overwhelm any imperative to find the correct answer.

“Only the experts, then, can tell us who is truly an expert. Only someone untrustworthy would not trust them.”

One of the most telling failures is the infamous “hungry judges” study, in which the rate at which judges give favorable decisions (acquittals and relatively light sentences) starts high each day, deteriorates as the morning proceeds, and hits zero just before a lunch break, before returning to its earlier level once the judges have eaten. The study, a mainstay of cognitive science textbooks and their discussions of human deviation from rationality, has succumbed to a number of attacks. Most interesting is the common-sense observation of psychologist Daniel Lakens:

I think we should dismiss this finding, simply because it is impossible. When we interpret how impossibly large the effect size is, anyone with even a modest understanding of psychology should be able to conclude that it is impossible that this data pattern is caused by a psychological mechanism. . . . If hunger had an effect on our mental resources of this magnitude, our society would fall into minor chaos every day at 11:45. Or at the very least, our society would have organized itself around this incredibly strong effect of mental depletion. Just like manufacturers take size differences between men and women into account when producing items such as golf clubs or watches, we would stop teaching in the time before lunch, doctors would not schedule surgery, and driving before lunch would be illegal. If a psychological effect is this big, we don’t need to discover it and publish it in a scientific journal—you would already know it exists.

Lakens is not merely asserting here that the non-expert’s common sense is sufficient to contest the expert’s study. He is suggesting that common sense remains an essential part of the expert’s arsenal. The apparent expert who abandons it may end up worse off than the non-expert.

Experts are also susceptible to processes that arbitrarily reinforce an unexamined consensus, both ex ante and ex post. The linguist and left-wing political commentator Noam Chomsky has noted that the technocrats who express their expertise through public policy form a kind of “secular priesthood.” If admission to the priesthood requires demonstrated commitment to certain beliefs, then the deck is already stacked. The consensus view is a prerequisite for qualifying as an expert, not a considered consequence of one’s genuine expertise. Chomsky has always made this case about American foreign policy. But academia and journalism now conduct such sifting quite explicitly, with mandatory diversity statements that function as political pledges and high-profile firings of those who manage to slip through the cracks.

“Take the world’s most famous diversity consultant, Robin DiAngelo, Ph.D., whose degree is in “Multicultural Education” and whose “area of research” is “Whiteness Studies and Critical Discourse Analysis.” On what field of propositions would we expect her to be an authoritative source and ask the typical non-expert to defer, setting aside his own judgment for hers?”

Once qualified, experts remain susceptible to the related phenomenon of belief cascades as new questions emerge, because they place their standing at risk if they depart from the views of fellow experts. (After all, what could threaten the enterprise more than the revelation that expertise does not dictate a particular conclusion?) When one expert, or a small number of experts, expresses a certain view—especially on a politically charged topic—that view quickly propagates through social networks both formal and informal, public and private, and becomes widely held on the assumption that experts can be trusted. What appears a broad-based consensus among people who have thought about the issue is really only the overamplified view of the few people who have thought about it at all.

Yet another problem for our experts is that the source, nature, and relevance of their expertise is often ill-defined. A degreed professional like First Lady Jill Biden might want to be called “Doctor,” but even those who accede will struggle to articulate just what kind of knowledge she has that the rest of us lack. What is the knowledge-how or knowledge-that accompanying a doctorate degree in educational leadership? Or take the world’s most famous diversity consultant, Robin DiAngelo, Ph.D., whose degree is in “Multicultural Education” and whose “area of research” is “Whiteness Studies and Critical Discourse Analysis.” On what field of propositions would we expect her to be an authoritative source and ask the typical non-expert to defer, setting aside his own judgment for hers?

Even when expertise is genuine, disciplines and professions, along with their practitioners, seem determined to overextend its breadth for purposes of laundering their personal, non-expert opinions under their expert brand. In the summer of 2020, over a thousand public-health researchers signed a letter expressing their support for mass public protests in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, even as they insisted that in all other contexts the COVID-19 threat weighed against such gatherings. In The Atlantic, under the headline “Public Health Experts are Not Hypocrites,” Harvard Medical School professor Julia Marcus and Yale School of Public Health professor and MacArthur “Genius Grant” winner Gregg Gonsalves proposed that “systemic racism” was itself “a pervasive and long-standing public-health crisis.” By expanding the reach of the term “health,” the authors seemed to think they could also expand, as though by linguistic fiat, the breadth of their knowledge about the world, and demand new deference on matters of morality and politics. The signatories were public health experts, and systemic racism was a public health crisis, ergo the signatories were systemic racism experts.

“To become visible enough that non-experts can find him, he must proffer his views through Twitter, on talk show interviews, and in essays for magazines like The Atlantic. Such platforms select for certain experts, and certain views. Laypeople encountering an expert “in the wild” have no reason to think that he is representative of his discipline and every reason to think the opposite.”

Of course, such justification by stipulation is no justification at all. Marcus and Gonsalves never managed to explain what special insight a public health expert might have on the benefits of nationwide protests, or why anyone should defer to their conclusion that “the health implications of maintaining the status quo of white supremacy are too great to ignore, even with the potential for an increase in coronavirus transmission from the protest.” Making matters worse, they warned that even asking, “How many new infections from the protests will public health experts tolerate?” is an impermissible “call to color blindness, to stop seeing the health effects of systemic racism as something worthy of attention during the pandemic.” Now they were self-declared moral experts in two ways: qualified to adjudicate a divisive political debate, and further qualified to scold those who might question that initial qualification. They didn’t just know better than us; they were better than us.

On one hand, it might seem unfair to highlight absurd and overstated rhetoric as characteristic of the public health community. On the other hand, this is the view that The Atlantic chose to present as the expert one, which illustrates perhaps the modern expert’s biggest problem: To become visible enough that non-experts can find him, he must proffer his views through Twitter, on talk show interviews, and in essays for magazines like The Atlantic. Such platforms select for certain experts, and certain views. Laypeople encountering an expert “in the wild” have no reason to think that he is representative of his discipline and every reason to think the opposite.

Rather than help to correct this distortion, markets can compound it by elevating experts whose expert recommendation is to buy more of their services. The “Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion” (DEI) industry, for instance, sends confident, well-dressed people with lengthy but opaque credentials to train corporate workers and college students in the ever-evolving intricacies of progressive politesse. Their expertise is in interpreting—or “problematizing,” in the idiom of DEI—every event and attitude as one in need of further DEI services. A DEI consultant whose “equity audits” turn up few issues requiring months of intensive work would fade into irrelevance. The one who discovers an immediate need to double the staffing and resources of the department who hired him will have ambitious customers banging down his door.

* * *

A few months after the public-health-approved protests, another expert letter circulated. More than 50 former intelligence officials, including 4 former directors of the Central Intelligence Agency, signed a statement questioning the provenance of emails found on a laptop purportedly belonging to Hunter Biden, son of then-Democratic nominee and now-President Joe Biden. The letter warned that the laptop had “all the classic earmarks of a Russian information operation” and, in italics, that “if we are right, this is Russia trying to influence how Americans vote in this election.” While the officials were careful to acknowledge that use of information in a foreign intelligence operation would not rule out the possibility of its authenticity, mainstream coverage eschewed this nuance. So did Biden, who declared to tens of millions of voters during a presidential debate that “there are 50 former national intelligence folks who said that what [Trump is] accusing me of is a Russian plant.” Most famously, Twitter suspended the New York Post for attempting to disseminate the story. In fact, no evidence has emerged of Russian involvement and the laptop and its emails proved authentic.

The letter had many of the hallmarks of untrustworthy expertise. The purveyors were “experts” in various national security fields. But they offered a judgment plainly motivated by an overriding political preference, on a question few had the actual expertise and none had the necessary information to answer. That the laptop could have been a Russian operation was something any two buddies could have come up with at a bar, not an expert opinion at all. Whether the laptop was a Russian operation, the experts had no idea.

“A supporter of Joe Biden who declares that an embarrassing trove of Hunter Biden emails is fake may very well be correct and is entitled to make the case, but his listeners are similarly entitled to doubt his cogency or his sincerity. A supporter of Joe Biden who studies poisonous spiders for a living should be deferred to when he warns that the spider on your arm is poisonous.”

The public will never be able to assess the validity of expertise on a case-by-case basis. Trying yields widely varied conclusions and thus eliminates any common starting point from which to conduct public debates—roughly the situation today. Assessing apparent expertise requires knowledge of a field’s inner workings, something almost no one has the time or inclination to learn. From the outside, it is difficult to infer what dogmas might contaminate a discipline’s standard training or what pressures might distort processes of hiring, promotion, and socialization. However, some general heuristics and defaults might provide a basis for at least some agreement.

First, a simple conflict-of-interest standard would make sense. Look at what people gain from giving their views, and from whom they gain it. Someone who stands to gain more personally from one view than from another should not be entitled to deference when offering the former. That does not mean the view is wrong, only that it must be defended on its merits rather than based on the identity of the speaker. A supporter of Joe Biden who declares that an embarrassing trove of Hunter Biden emails is fake may very well be correct and is entitled to make the case, but his listeners are similarly entitled to doubt his cogency or his sincerity. A supporter of Joe Biden who studies poisonous spiders for a living should be deferred to when he warns that the spider on your arm is poisonous.

Second, political stances should be inherently suspect. Experts can offer knowledge useful in evaluating the values-laden tradeoffs of politics and public policy, but that expertise does not make their judgment superior to that of any other citizen, and certainly not the democratic determination of a large group of citizens. This is not to say that no one can be a moral expert, only that technical expertise is not moral expertise. Plenty of people defer to religious leaders, community leaders, and even political leaders when it comes to questions of what to value and how to act. But in doing so, we should be aware that our moral experts will not be our neighbor’s. Identification of moral experts often depends on prior moral and political convictions, and disagreement on who the experts are will tend to mirror disagreement about the underlying issues.

Third, we should be far more skeptical of claims of knowledge-that expertise than of knowledge-how. In the latter case, people’s claims of expertise can be substantiated by their ability to deliver objective results. The surgeon with a track record of successful surgeries is easily distinguishable from the charlatan with none. Knowledge-that experts, by contrast, are laying claim to the truth. Sometimes they have it, and are guiding us as reliably as a pilot. Other times they are simply taking us for a ride.

Nothing is more useful, though, than one-on-one discussions, which allow a non-expert to get a sense of the true reasoning, beliefs, motivations, and character of an expert. In private, back-channel discussions, people are often eager to be honest, even when that honesty reflects poorly on themselves or their profession. When it’s possible to observe just where exactly the expert draws their certainty from, non-experts may find themselves convinced, or they may find themselves skeptical. A surprising number of issues come down to matters like a preference for more complex explanations over simpler ones, a vague sense that certain kinds of theories have fared poorly in the past, a conviction that a field should take a stance on important matters, and so on. Identifying these points of departure and working through one’s own thoughts on them is a more valuable epistemic activity for a democratic citizen than simply deferring to an increasingly distant and unreliable expert class.

Recommended Reading

The Edgerton Essays

Perspectives from the Working Class

Introducing the Edgerton Essays

The goal of these essays is to help inform policymakers and pundits about what matters most and why to the vast majority of Americans who have no day-to-day connection to our political debates.

Deadly Sins of Left & Right

Rod Dreher reflects on the political sins identified by Ruy Teixeira and Henry Olsen in their American Compass essays.