RECOMMENDED READING

One way of reading a story of American discontent is in its newspapers. Not just in their pages, but in how their ongoing decline illustrates broader tendencies fueling popular frustration.

Local newspapers used to be the only game in town. National news came off the wires, opinion columns were syndicated, and each town was its own market. An aspiring scribbler with newsprint in his veins could pound the pavement covering city council meetings and crime scenes. His reward might someday be a columnist gig or the editor’s desk, an influential post in any two-newspaper town.

The internet changed all that, distorting both the economic engine that made local news profitable and the incentive structure for going into journalism in the first place. News could come from anywhere, for cheap, reducing the economic rationale of syndication or wire services. With fewer beat reporters and fewer local readers, newspapers were no longer a heritage investment owned by local scions, but a vehicle for private equity to strip-mine for assets.

This means that aspiring journalists now set their sights on high-prestige national publications, like a dataviz gig with Vox, churning out content for The New Republic, or freelancing for The New York Times, the 800-pound gorilla that has succeeded amidst the culling of the dailies. (This dynamic, incidentally, has the side effect of increasing media bias – why question groupthink when a hungry bench of would-be replacements is snapping their jaws?)

Media is just one industry, and a navel-gazing one at that. But the decline of mid-tier hometown fishwrap illustrates the one-sided truth of “elite overproduction,” the beguiling phrase popularized by Russian-American polymath Peter Turchin to describe the dynamics of social inequality.

A relative oversupply of lawyers and other graduate degree holders, Turchin has speculated, means “A large class of disgruntled elite-wannabes, often well-educated and highly capable, has been denied access to elite positions.” This leads to social rupture. Turchin notes the Occupy Wall Street movement wasn’t a Les Miserables moment. The children of the well-to-do felt that they were being denied a place in society commensurate to their level of human capital formation.

Turchin’s theory has some merit, at least when it comes to post-baccalaureate education (using a history Ph.D to teach surly teenagers at an elite prep school might inspire some amount of ressentiment in all but the most virtuous.) But it surely misses the other side of the equation – elite overproduction wouldn’t be nearly as big a problem if there were still sufficient places in which to be elite.

Just as every young journalist has to aim for The New York Times or bust, the economics of agglomeration and “superstar cities” means a young person aspiring for influence feels no choice but to look past Akron or Indianapolis for Seattle or San Francisco. This dynamic is seen in the nationalization of politics and the thin bench in many state capitals. It’s seen in banking, where mergers and regulatory rollback allowed more and more branches to be controlled from New York or Charlotte. And on the cultural level, as an incisive piece from Michael Lind in Tablet points out, it has led to homogenization and the replacement of the local aristocracy by a national ruling class.

A recent NBER working paper helps illustrate just how “superstar cities” might be contributing to a sense of “elite overproduction” by leaving the rest of the country behind. Cecile Gaubert, Patrick Kline, Damián Vergara and Danny Yagan find that incomes between states have notably diverged since the mid-1990s, driven by rising incomes on the top end.

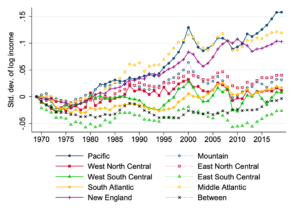

The graph below shows the relative growth in the standard deviation of income across counties within Census regions from 1969 to 2019. A higher standard deviation means a wider degree of dispersion in income, or a greater gap between the wealthy and the rest of the households in the region.

Income dispersion across U.S. counties by region, pre-tax income plus transfers

Source: NBER Working Paper 28385, Figure 3(d)

Income divergence has increased fastest in the New England, Mid-Atlantic, and Pacific regions – home, of course, to Boston, New York, Washington, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Seattle. The authors find the increasing dispersion in income is not at the state level, but from certain “counties within these states [] driving the steady increase in county level inequality.”

Meanwhile, the spread between rich and poor only moderately increased, if at all, in the rest of the country. (In the region made up of Alabama, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Mississippi, the income distribution actually compressed.) And on the low end of the spectrum, incomes have converged, so the poor and working-class are now more likely to see similar incomes across states and counties.

This finding suggests the isolation of the elites in those influential “superstar cities” is more dramatic than the elite-middle class gap elsewhere. As R.R. Reno previously noted on The Commons, the pattern of self-segregation was noticed most starkly in Charles Murray’s Coming Apart. The “extraordinary insularity of elites (and insularity amped up by increasingly punitive attitudes toward dissent),” Reno suggested, means “opinion-makers need to share more of their lives with and listen to the people they purport to speak for.”

Certainly they should, whether that is through welcoming greater socioeconomic mixing in their own neighborhood or by leaving Lexington Avenue for Lexington, Kentucky. And no one knows what the long-term ramifications of Covid-19 mean for top-tier cities. Rents have fallen in San Francisco, crime has risen almost everywhere, and more tech start-ups are intrigued by remote work than anywhere specific location. Some of the scales tipped towards elite hubs may indeed rebalance in the aftermath.

Just like with newspapers, some technological change may have been unavoidable. But other policy decisions have contributed to loss of stature in middle-tier cities and may be worth revisiting. Shifting economic incentives to help create more of those places could look like subsidiarity, deregulation, or even re-regulation – but it should be something explicitly on policymakers’ agendas. We might blame “elite overproduction” a little less, and instead seek to prioritize cultural and economic production of mid-tier places where aspiring business owners, lawyers, and public servants can find fulfillment in helping lead.

Recommended Reading

Introducing the Edgerton Essays

The goal of these essays is to help inform policymakers and pundits about what matters most and why to the vast majority of Americans who have no day-to-day connection to our political debates.

A Culture Canceled

The current debates over cancel culture are odd because few involved in them have been canceled, or risk being canceled, while entire institutions are indeed being canceled. Institutions that serve and amplify the interests of the working class, such as local newspapers, unions, and churches.

Dignity to Endure

After spending eight years driving four hundred thousand miles to take 60,000 pictures of working class Americans, I could easily write a Labor Day essay on the dignity of work, topped by a photo of a man dirty from work, leaning on his well cared for F150 with a back-rack, silver tool box, two bright yellow cylindrical Igloo coolers, and pissing Calvin mud-flaps.