RECOMMENDED READING

Ever since the concept of a national industrial policy was proposed in the 1970s, it has received scorn from most neo-classical economists, with those advocating it treated as the economic equivalent of chiropractors.

But recently the idea is getting a new life, largely because of the growing awareness of the economic, technology and national security threats posed by China.

Case in point is the recent House Republican’s China Task Force Report. Who would have thought that a party that was heavily influenced by the Freedom Caucus just a few years ago would be calling for a national industrial policy, including doubling federal funding for basic science, expanding industry-university-federal lab partnerships, expanding funding to help spur innovation in lagging regions, and doubling the R&D tax credit? Likewise, Senator Rubio (R-FL) has tried to reorient the Small Business Administration more toward innovation and traded sectors. The bipartisan CHIPS Act would provide upwards of $30 billion to help grow and attract semiconductor firms. The Endless Frontiers Act provides $100 billion for research in 10 key technologies. And the Democratic LEADS Act would invest $300 billion in a national industrial policy. And finally of course, the election of Joe Biden will put industrial policy front and center, with his Build Back Better plan.

So far so good. But things could easily go off the rails, for industrial policy is not an end; it’s a means. Industrial policy refers to a coherent set of policies and programs focused on particular industries and technologies, rather than the overall economy. As such, its not enough to put in place any kind of industrial policy; it has to be the right kind. Unfortunately, many on the left are advocating for industrial policies that would do little or nothing to boost advanced industry competitiveness.

Overall, there are at least five types of industrial policy vying for attention.

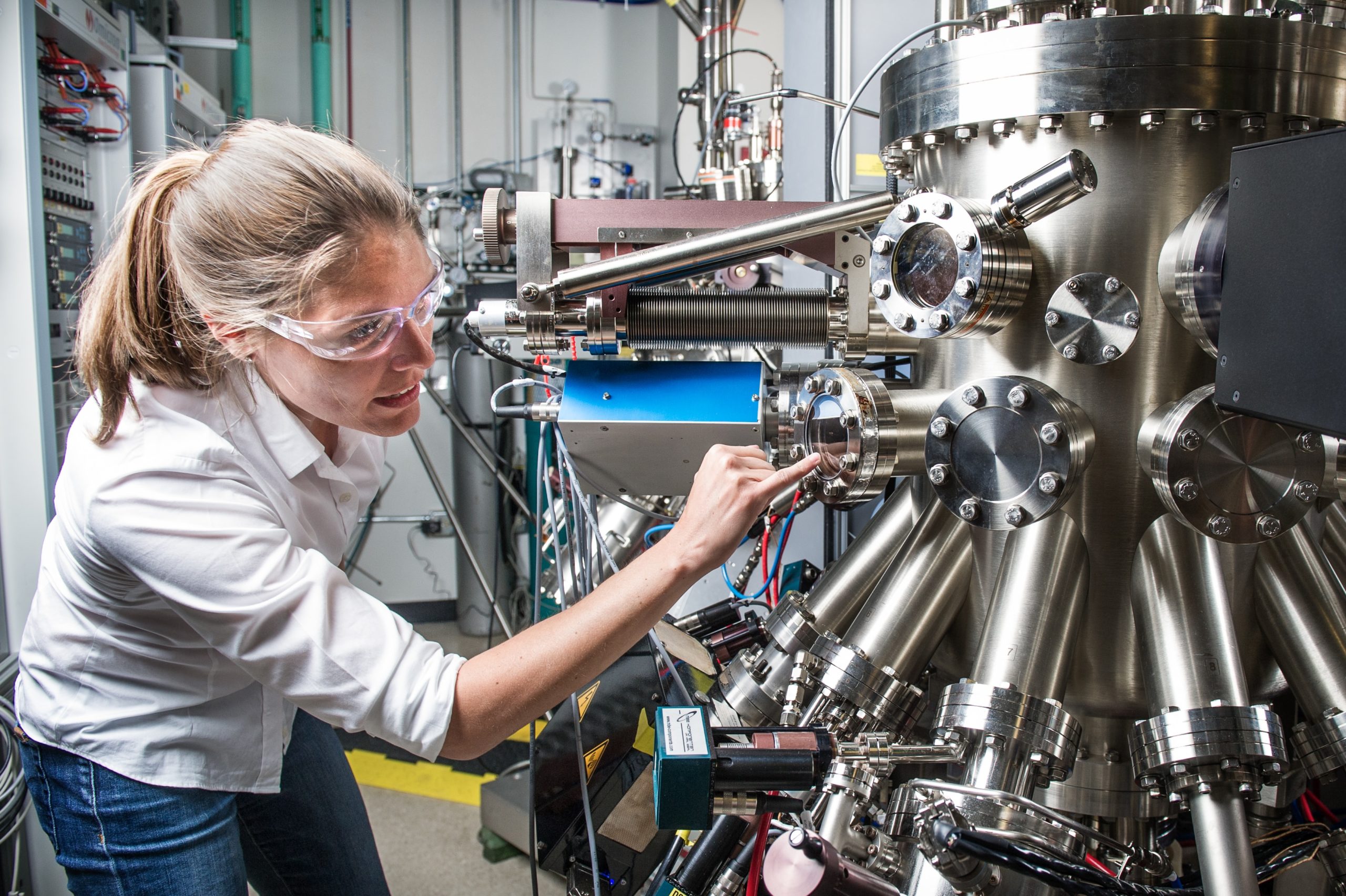

Competitiveness Industrial Policy: Mainstream industrial policy proposals focus on boosting competitiveness in technologically advanced, globally-traded sectors. They are grounded in the reality is that China is “gunning” for U.S. technology leadership, which if they achieve it, will mean fewer good jobs, a weaker U.S. dollar, less innovation at home and globally, and a weakened U.S. national security capability.

Climate industrial policy: Some want industrial policy to be in the sole service of climate change, with the lion’s share of any funding going to things like EV charging stations, home insulation, clean energy research, and high speed rail. For example, Mariana Mazzucato advocates a green industrial policy that focuses on “innovative transformations across all sectors, one of the largest shifts ever attempted by humans.” While we need clean energy innovation, and any competitiveness-based policy would include some clean energy technologies like batteries and EVs, focusing principally on “green” would mean ceding U.S. competitiveness to China.

Social goods industrial policy: Some want to focus on technologies to improve quality of life. Weller, Farooque, Govani, and Kaplan would reorient the Endless Frontiers Act to support “hybrid learning tools and pedagogies to broaden access to high-quality education…, energy technologies.. that align with communities’ values and priorities and [technology for] neglected and hazardous infrastructure.” They note that they are not pushing these goals, “just for the sake of not losing scientific leadership to China” which they see as some kind of jingoistic corporate competition. “What does outcompeting China in new technologies—as Senators Schumer and Young seek to do—mean if we fail to advance American ideals of equality, justice, and opportunity?” Likewise, Fred Block, a scholar who once forcefully advocated for a competitive-based industrial policy, now seems to have switched, advocating for an industrial policy focused on affordable housing and expanding small business financing. The reality is that strong and competitive advanced industry sectors make achieving all these goals easier.

Worker opportunity industrial policy: Some would go further and orient an industrial policy to principally help workers. Cassandra Lyn Robertson and Darrick Hamilton write in the American Prospect that “By reframing policies that benefit the worker as industrial policy, we can imagine new ways of intervening in the economy that directly benefit the worker and the economy overall.” Among the industries they would prioritize for assistance are “child care, elder care, health care, and housing,” in part because “these jobs that cannot be outsourced or automated.” But the U.S. does not face a jobs shortage (or at least won’t once the COVID crisis is over); it faces a good jobs shortage, and overall these sectors do not provide good jobs. Moreover, we don’t need to compete globally for jobs that cannot be outsourced – child-care jobs are not going to Mexico or China, but semiconductor and auto jobs might.

Economic Inclusion Industrial Policy. A version of worker-oriented industrial policy would focus particularly on women and minorities. For example, the Roosevelt Institute argues that, “Industrial policy… can and does encompass every industry, including service sector ones like care work, convenience stores, cosmetology and barber school, and home health-care services. Any industrial policy regime worth its salt would spend at least half of its energies on the service sector.” This is because “Work in the service sector is disproportionately female,” and “The service sector is also where we see higher shares of people of color.” But as above, we face no shortage of low wage jobs in these sectors; they aren’t subject to foreign competition. Rather, any focus should be on boosting traded sector competitiveness and ensuring that more women and people of color gain opportunities in these sectors.

If America is to regain its technology leadership, create good jobs, and ensure national security a new U.S. industrial policy needs to be focused on advanced industry competitiveness. That doesn’t mean that other goals cannot be made part of that. For example, any competitiveness-focused industrial strategy should include a strong focus on clean energy technologies like small module reactors, next-generation solar, batteries, and electric cars. And any strategy should work to ensure that workers, including women and people of color, benefit.

U.S. economic policy is at a major crossroads. After 50 years of the dominance of the neo-liberal, neoclassical economics paradigm we appear to be finally moving to a world where a smart, interventionist role for government is not only not just rejected out of hand as the musings of some misguided economic equivalent of a chiropractor, but actually seen as a core part of U.S. economic policy. As such, it would be a tragic mistake to use opening of the “Overton window” to craft an industrial policy focused on goals other than restoring U.S. global economic, technological and manufacturing leadership.

Recommended Reading

No, Adopting an Industrial Policy Doesn’t Mean We’re Emulating China

There is a continuum of state involvement in industry and technology policy that spans from doing nothing to picking particular firms and technologies.

Policy Brief: A Domestic Development Bank

Financing American industrial development

Issues 2024: Industrial Policy

A strong industrial base is vital to workers and their communities, the rate of technological and economic progress, and national security.