RECOMMENDED READING

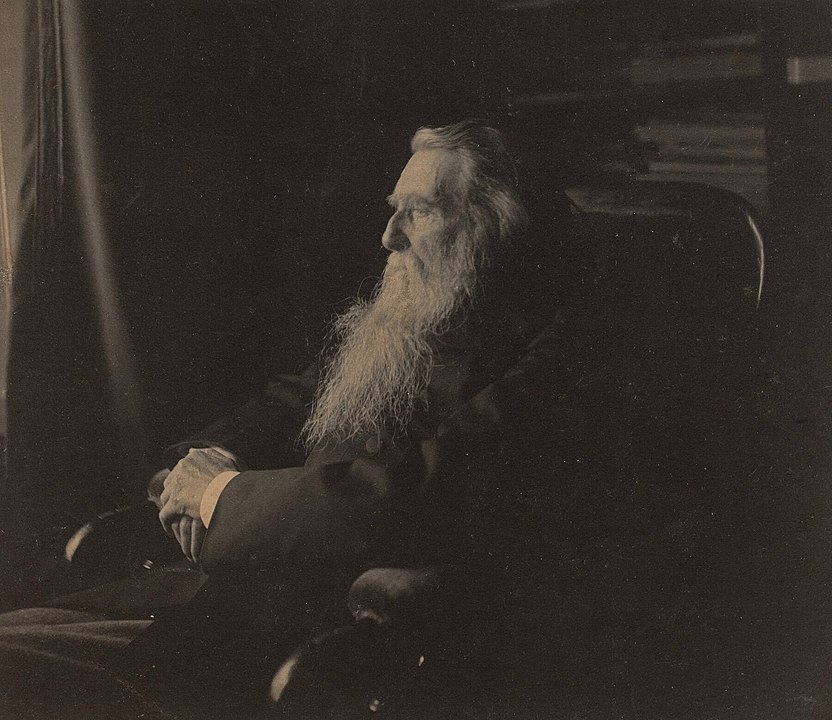

As we seek a realignment in American political economy we would do well to rediscover the thought of a 19th-century critic who did not like us very much. John Ruskin (1819–1900) found Americans obsessed with a liberty he considered license and naively committed to an ideal of equality he believed impossible: “also, as a nation, they are wholly undesirous of Rest, and incapable of it.” In her utilitarian preoccupation with commercial ventures, America had inherited Montaigne’s English vice of inquietude and seemed unlikely to recover. Despite this disdain, or perhaps because of it, we should attempt to learn from the man. Long-time readers and friends may find this me—if not beating—still massaging a dead horse, or rolling out a beloved soapbox battered with use, but I beg no excuse. Repetitio est mater studiorum.

While the skepticism of liberty and egalitarianism might suggest a man firmly of the right, it has been socialists who have kept Ruskin’s political memory alive. I recommend this essay on him from the left by Eugene McCarraher. Today, Ruskin is largely remembered for his early work, as an aesthetic theorist focused on painting and architecture. But by 1860, when he published Unto This Last, from which most of the quotes here are taken, he was writing and working almost exclusively on social issues in general and political economy in particular, though still very much with an eye for beauty.

The Industrial Revolution and the world it was forming was profoundly ugly in Ruskin’s gaze. The future looked to be one of anarchy or a base materialist oppression that would make the good life impossible for rich and poor alike. The European revolutions of 1848 had been an alarm, waking Ruskin to the plight of the working class and the fragility of social order. That year also saw the publications of Marx’s Communist Manifesto and Mill’s On the Principles of Political Economy. Mill’s utilitarian theories received significant attention from Ruskin.

[Mill] deserves honour among economists by inadvertently disclaiming the principles which he states, and tacitly introducing the moral considerations with which he declares his science has no connection. Many of his chapters are, therefore, true and valuable; and the only conclusions of his which I have to dispute are those which follow from his premises.

Mill, Ruskin believed, had often touched the truth, lightly, without recognizing it, and he enjoyed the opportunity to point this out. But he also feared that an ethical and moral dimension of political economy was being ignored by the politicians and theorists of his day, and this promised disaster.

Ruskin wrote that ruin, “can be arrested only, either by the repentance of that old aristocracy, (hardly to be hoped,) or by the stern substitution of other aristocracy worthier than it.” For those convinced that the troubles of today are ones of mismanagement and not material necessity, Ruskin’s concerns about the aristocracy still ring true. A selfish managerial elite has failed in its assignment to govern the country and global order with an eye to the common good, or even basic prudence. Despite our preoccupation with liberty and equality, Americans have discovered that our attempted meritocracy is no defense from bad aristocrats; they emerge anyway, no longer aristoi, but strivers among strivers. Ruskin offers a theoretical correction. Politics was to him, “the science of the relations and duties of men to each other,” and so political questions are questions of social duty, of enabling citizens to fulfill their responsibilities towards their fellows. We too must seek the other aristocracy worthier than our still unrepentant managers.

But this is still elitist, you might think. Yes. Ruskin believed class dynamics were unavoidable. This was not only a matter of necessity; he also believed that it was in the diversity of social position and personal abilities that the relations and duties of human beings, one to another, had fullest expression. His skepticism of egalitarianism was rooted in an ethical concern. There are no acts of charity one can owe one’s neighbor if all are the same. Fellow feeling is not enough; it is only a feeling.

But inequalities of wealth, justly established, benefit the nation in the course of their establishment; and, nobly used, aid it yet more by their existence. That is to say, among every active and well-governed people, the various strength of individuals, tested by full exertion and specially applied to various need, issues in unequal, but harmonious results, receiving reward or authority according to its class and service; while, in the inactive or ill-governed nation, the gradations of decay and the victories of treason work out also their own rugged system of subjection and success; and substitute, for the melodious inequalities of concurrent power, the iniquitous dominances and depressions of guilt and misfortune.

Of course the struggle here is what it has always been: How to ensure that the inequalities of wealth are justly established? By what measure should we judge the use of material resources and human labor?

As industry suggested the possibility of a post-scarcity future, Ruskin sought to set aside the simple material paradigm of wealth and poverty. It was not enough to measure having against having-not, rather, wealth should be that which is conducive to life and a life lived well, and its opposite should account for the misuse of resources.

I believe nearly all labour may be shortly divided into positive and negative labour: positive, that which produces life; negative, that which produces death; the most directly negative labour being murder, and the most directly positive, the bearing and rearing of children: so that in the precise degree in which murder is hateful, on the negative side of idleness, in that exact degree child-rearing is admirable, on the positive side of idleness.

This holistic idea of wealth, and this economic telos of life, led Ruskin to coin the term “illth.” “Illth” is un-wealth, the material possessions that do not contribute to fulfilling the responsibilities we owe to ourselves and our fellow citizens. A “Common-illth” exists alongside the “Common-wealth” of a nation.

It is in large part due to the influence of Ruskin on my own thinking, and especially this idea of “illth,” that I eagerly became a member of American Compass, and look forward to contributing to the Commons. Wells King’s introduction to “Coin-Flip Capitalism” is not just a primer on the national utility or non-utility of the hedge fund, private equity, and venture capital industries; it is a primer on “illth” in action (or non-action). Oren Cass’s “Cost of Thriving”, like Ruskin’s account of wealth, reminds us that production and consumption must be measured by a human scale, by people’s lives and by their ability to make new life and raise those children well. Ruskin wrote, with his very Victorian affection for capital letters, “THERE IS NO WEALTH BUT LIFE. Life, including all its powers of love, of joy, and of admiration. That country is the richest which nourishes the greatest number of noble and happy human beings.” So I say read Ruskin. And may those who, in whatever way, direct the use of our country’s riches take up their responsibility for the lives of their fellow Americans.

Recommended Reading

Realignment Politics with Jerry Seib, Michael Brendan Dougherty, and Tim Chapman

What does the right-of-center’s economic debate mean for political leaders and how is it being translated into electoral politics in 2024 and beyond?

Patrick Ruffini on Populism and the Realignment

On this episode, Oren Cass and pollster Patrick Ruffini discuss Trump’s reshaping of the GOP and the challenges ahead

Political Analysts from Left & Right Explain How Their Own Side Fails the American People

PRESS RELEASE—American Compass’s October collection explores how Democratic and Republican establishments have been co-opted by a ruling class with little connection to most Americans’ needs.