RECOMMENDED READING

No particular worldview or ideology is necessary to see the reality of our political situation today. Due to the reshaping of our psychological and social environment by digital technology–a process laid bare by the unfolding coronavirus pandemic–our “map” of America is now out of date. Deep-seated economic and cultural transformations that began decades ago have burst through the terrain we knew, throwing up strange and vast new features and breaking up or plowing under long-familiar ones.

This process has only just begun. Many Americans, including at the highest levels of leading pre-digital institutions like academia, media, entertainment, and the administrative state, struggle to make sense of the new topography rising all around (and, indeed, within) them. Some strongly refuse to recognize that anything fundamental has changed: perhaps the speed or the complexity of our problems has increased, they suggest, but so have our potential solutions.

This is a mistake. The task facing today’s and tomorrow’s practitioners of American statecraft is to quickly and fully come to a reconciled understanding of what has already happened–a point conveniently lost on those apt to hawk ostensibly cutting-edge forecasts or prognostications about the future. Plenty of roads lead to the Rome of recognizing the new America rising up into the foreground. Some are more readily apprehensible than others. Here are a few that leap into sharp relief.

Deindustrialization

To the deepening chagrin of the more nationalist or populist Right, the America of today is one that has, for generations on end, aggressively deindustrialized. With good reason, blame is characteristically laid at the feet of various globalist elitists and the institutions they (now rather shakily) control. Without question, the deindustrialization of America became a prominent theme for policymakers who understood it was necessary to retool our economy for optimization in the globalized western system built in the first decade after the end of the Cold War. With that system now in all but a shambles, yet its officer class more unwilling than ever to relinquish power, the ambition on the Right to correct for the failures of globalism by putting reindustrialization at the center of contemporary statecraft is, to a great degree, natural and salutary.

But there is a complication: the main driver of deindustrialization has been innovation itself, in the form of the development of digital technology from its first online stirrings in the 1970s and the advent of the personal computer in the 1980s. There is no going back to a time when mass industrial employment by human laborers can function technologically, economically, or socially like it did in the decades following America’s world triumph in the production of goods after World War Two. Reindustrialization today will involve more automation than in the past and a serious emphasis on the production of digital or digitized goods, which typically condense formerly broad lines of physical products into components–often disincarnate–of much narrower lines. We are just beginning to size up the implications of these changes for employment, economic output, trade, standard of living, and interpersonal arrangements such as family formation.

Deconsumption

Digital technology should incline us toward throwing out the map of America’s pre-digital production patterns and the socioeconomic assumptions around them. But because the new digital environment is comprehensive, both here and around the world, we should be prepared to do the same when it comes to the map concerning our consumption patterns too. The work of Milton Friedman is vulnerable to being lumped in with standard or stereotypically liberal theory. But one of his unwisely neglected ideas–that economic theory should focus on modeling consumption instead of production–deserves a renewed focus. It is plain to see that consumption, which once drove and defined American economic dominance and the flourishing of the American people, is well on its way to cratering. Access now matters more than ownership. No one can consume all the content on offer today, but more importantly, no one wants to consume anything but a diminishing sliver. Only the best commands respect, and the culture of curatorial snobbery and obtuse “references” has become cringey. Ad revenues continue to decline, even though ad spend, rushing into the online space, spiked in recent years. Americans don’t want to watch and don’t trust ads, or, increasingly, the people they see in them. One does not have to go full Silicon Valley Minimalist to experience and embrace a deep loss of interest in the endless clutter of material possessions and conspicuous expenditures that once typified Americans and their homes virtually regardless of economic class.

Again, while worldview or ideology has some clear influence, in the form of guilt-ridden environmentalism, woo-woo detachment, or a cosmopolitan devotion to the mid-century modern aesthetic, the far greater determinant is the digital medium that now suffuses how we live, how we communicate, how we think, and how we see the space around us. Policymakers must accept that the task of American statecraft now includes responding to persistent and irreversible declines in consumption as we knew it before the rise of digital–and, most likely, consumption as such.

Decompetition

For decades in the run-up to the triumph of digital, academic political theory was consumed by a debate between relatively more libertarian and relatively more communitarian liberals. These debates reflected a broad anxiety over the politics of competition, with Americans craving on the one hand a “sense of personal empowerment” and on the other a “sense of togetherness.” Under digital conditions, the underlying conditions that gave rise to the long-familiar politics of economic and psychological competition have shifted dramatically. Capitalism in America was once defined by the interplay of millions and millions of mature adult fathers entering marketplaces with reasonably well ranked preferences ordered around maximizing the security and felicity of their households. At the same time, American politics was defined by the “marketplace of ideas,” where various notions and plans contended more or less openly for the attention and support of those men. Already, in the age of television, economic and psychological competition shifted into a mode of rival fantasies, where dad’s longing for a second honeymoon did battle with the kids’ demands for Disney World, and where the marketplace of ideas was supplanted by a global theater of propaganda war.

Now the terrain has shifted again. Digital life is a realm where identity matters more than idea and memory more than fantasy. The rewards for enduring the rigors of competition are losing their savor at the same time that the costs of exposing oneself to competition are sharply increasing. Generations of young Americans have learned the hard way why not to chase relentlessly after one’s “dream,” which so routinely turns out to be somebody–or some entity–else’s. While we and all humans remain resolutely imitative creatures, and mimicry can sow a certain kind of competitive spirit, unintentional imitation is often even more socially powerful than intentional imitation, and leads even more toward outright enmity or harmony than toward competition. Competition exists in the experiential and perceptual realm between us and them. Digital experience is driving us to increase identitarian loyalty while decreasing our desire to interact with the other. It is less and less “worth it” to engage those unlike you, to argue, explain, persuade, cajole, and pressure another to change or come to agreement. Whole economies and industries built around monetizing those activities, and encouraging people to be drawn into general society to engage in them, are now coming into serious question. Policymakers must accept the responsibility of working out the implications in this area too.

* * *

Our uncertain political fortunes will doubtless be improved by the return in thinking on the Right to the importance and legitimacy of sound planning as a feature of statecraft. While we cannot be expected to do everything at once, much less do it well, incorporating a full reckoning with the realities of our digital life into the plans to come should be an immediate priority.

Recommended Reading

How Technology Has Changed Our Jobs, Our Privacy, and Our Brains

American Compass research director Wells King discusses the wide-ranging effects of the digital revolution in an adaptation of Lost in the Super Market: Navigating the Digital Age.

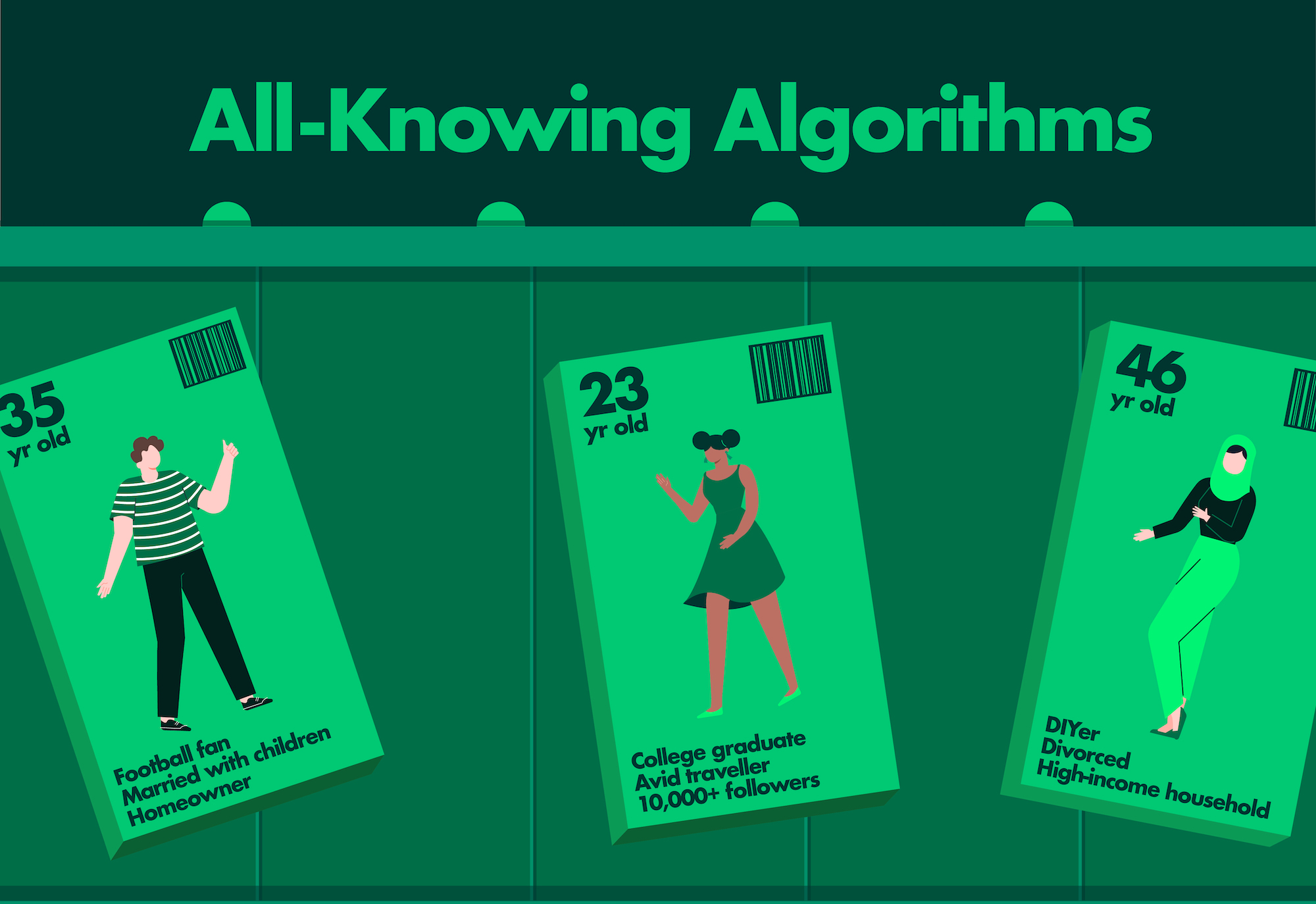

Selling the Digital Soul

The use and abuse of personal data pose a collective challenge that cannot be solved by individuals.

New Collection Calls on Policymakers to Rethink Governing in the Digital Age

PRESS RELEASE—Modern technology has reshaped markets fundamentally, requiring new policy responses to protect our values, institutions, and relationships.