Reforms to Public Policy and Employer Practice for the Benefit(s) of Homemakers

Recommended Reading

Executive Summary

American family policy is long overdue for a revolution. For decades, politics, economics, and culture have undervalued homemakers and put tremendous pressure on families with young children to have two working parents. This is backward. Of course, families that want to have both parents work should have that option. But those that would prefer to have one breadwinner and one homemaker caring for children should be able to do so—indeed, in recognition of its high social value relative to its economic reward, public policy should put a thumb on the scale in favor of homemaking.

This paper focuses on two related areas where public policy places homemakers at a significant disadvantage: access to social insurance systems and employer benefits. Both are built around an assumption of labor force participation. This passes a test of formal neutrality, but it fails to advance a goal of promoting and supporting homemaking as a different but equally worthy vocation. Robust family policy should “lean in” to ensure that families with one homemaker and one breadwinner can make the same use of social insurance and employer benefits as families where both parents work.

Public Programs

The federal government should provide robust social insurance for homemakers, in recognition of their importance to both families with young children and the broader social fabric. This support should accommodate homemakers moving in and out of the workforce; typically working before children are born, and then returning to the workforce as children become teenagers or adults.

- Social Security has changed little in its treatment of female, married homemakers since the 1930s and is poorly adapted to modern homemakers who work sporadically or with large gaps. Homemaker spouses caring for young children should receive “Caregiver Credits” that provide:

- Better social insurance at retirement through Social Security Retirement payments;

- Larger Social Security Disability Income payments in the event they become disabled; and

- Better access to Medicare later in life.

- Congress should also reform the Affordable Care Act to address the “Family Glitch” that prevents some families from accessing affordable health insurance on Marketplace Exchanges.

Employer Benefits

Unlike many other OECD countries, working American families rely on employers for benefits including retirement, disability, and health insurance. Families with homemaker spouses need:

- A family equivalent of an IRA (Family Retirement Account, or “FRA”), providing more tax-sheltered space for parents moving in and out of the workforce;

- Prioritization in employer-provided group health plans of affordable health coverage for spouses and children;

- Disability coverage for homemaker spouses; and

- Reforms to regulations covering employer-paid education expenses that would allow employers to pay for loan reimbursement for homemaking spouses.

Employers have always tailored benefits packages to meet social needs. What’s needed now is a focus on meeting the needs of families with a homemaker.

I. Why Homemaking?

As a sign of solidarity and protest, Democratic Congresswomen dressed in all white for President Donald Trump’s 2019 State of the Union Address. But they joined in a rare, bipartisan standing ovation when the president declared, “All Americans can be proud that we have more women in the workforce than ever before.” Left- and right-of-center policymakers in the U.S. don’t agree on much, but they do seem united in their determination to get both parents of young children to join the workforce.

On the left-of-center, politicians and thinkers focus on providing paid leave and subsidized childcare to promote two-income households. Such policies are based on the assumption that families, including working-class and low-income families, do better when children are cared for in institutional settings with professional staff who provide academic and other formal instruction, while parents are free to pursue paid work. Many left-of-center politicians also believe having both parents in the workforce is an important driver of economic growth. President Biden, for example, set a goal of ensuring that “the approximately two million women who left [work] due to COVID . . . [would] rejoin and stay in the workforce.” The Biden administration explained its goal as follows:

Our nation is strongest when everyone has the opportunity to join the workforce and contribute to the economy. But many workers struggle to both hold a full-time job and care for themselves and their families. [emphasis added]

In pushing for government-funded universal preschool, the Biden administration similarly argued that “[i]n addition to providing critical benefits for children, preschool has . . . been shown to increase labor force participation among parents—especially women—boosting family earnings and driving economic growth” [emphasis added]. Likewise, Secretary of the Treasury Janet Yellen mourned the dropping labor force participation of mothers: “Even before 2020, the percentage of working women was near its 40-year low, and then, COVID-19 dropped it to its nadir.” Secretary Yellen recommended using “the powerful tools at the federal government’s disposal” to encourage mothers’ workforce participation, including supporting publicly funded childcare.

On the right-of-center, meanwhile, organizations like the American Enterprise Institute (AEI) have led the charge for paid leave for the same reasons. In 2019, for example, AEI’s Aparna Mathur explained: “Access to paid leave has been shown to promote labor force attachment, especially for women, which is vital for economic growth. This is critical because research shows that the proportion of working women in the U.S. has fallen behind that of other countries, partially due to a lack of paid leave.” In 2021, the Republican National Committee tweeted: “1.5 million U.S. mothers have fallen out of the workforce, and many are staying home to take care of their children because schools have not re-opened. Biden is proving to be a detriment to getting mothers back to work.”

A. The Value of Homemakers

This bipartisan determination to supplant homemaking with outsourced childcare is misguided. Families may boost economic growth and GDP by sending both parents into the workforce, but sometimes only at significant cost to themselves and their communities.

Parent Preference

Most families with young children would like to have a stay-at-home parent. Those homemakers are likely to be women—while the number of families with homemaking fathers has risen in recent decades, it is still much more common for mom (not dad) to stay home with the kids. This, too, is what parents—both moms and dads—say they prefer.

A Gallup poll, for example, found that 56% of mothers with children under 18 would like to stay home, including 54% of mothers who were working at the time. Similarly, a Pew poll found that most Americans believe that children are better off with a parent at home, including 63% of men and 55% of women. A 2021 American Compass survey found that a strong plurality and nearly an outright majority of working-class parents preferred to have one stay-at-home parent taking care of young children and one working parent over any other arrangement. Indeed, that survey found that the most popular choice among lower-class, working-class, and middle-class adults was to have a homemaker. Only upper-class parents preferred to have two full-time, working parents and their children in full-time, paid childcare.

The preference for homemaking is particularly strong for lower- and working-class families, and for ethnic groups whose culture and traditions reinforce it. Lower- and middle-income Hispanic families, for instance, are particularly likely to benefit from policymakers’ support for homemakers. As the Institute for Family Studies observed:

Rather than maximizing each adult’s own career outside the home . . . one parent at home caring for children while the other parent works outside the home is an indicator of what can be described as “Hispanic familism.” Hispanic familism emphasizes the family as a single economic and social unit where all household members make some sacrifices for the good of the whole. Hispanic familism is also associated with the belief that children are essential for happiness, which may change the calculus that Hispanic parents have about the relative value of caring for children versus working outside the home. In particular, when it comes to child care, . . . Hispanics are more likely than other American parents to prefer that parents or kin take care of young children and to follow through on this orientation by having family members care for their infants and toddlers.

Child Welfare

Looking beyond mom and dad’s own preferences, evidence strongly suggests that for many kids and babies, depriving them of the care of a dedicated homemaker and placing them instead in institutional childcare is the wrong choice. Numerous studies have shown that extensive, early daycare use can have significant and long-lasting negative impacts. For example, a landmark study on universal childcare in Quebec found that it increased long-term negative behavior, including aggression, depression, and even criminality. Boys were especially likely to struggle, as were children who already had behavior issues. Similarly, one recent study conducted by researchers at Vanderbilt University found that children participating in a state-funded public preschool program ended up worse off over the long term than a comparison group of peers. The preschoolers in the studied Tennessee program went on to have worse test scores and more disciplinary problems. Although there are also studies showing early, government-funded childcare can be beneficial to a child’s long-term development, many parents are right to be dubious about whether their young child will do better in institutional childcare than at home.

In general, the dividing line seems to be that high-quality daycare can have a beneficial impact on kids and babies, especially when the alternative would be an unstable home environment—but low-quality daycare has negative long-term impacts, especially when the alternative would be a supportive home environment. Policymakers may try to improve daycare quality through various measures, but that is a tremendously difficult problem they have shown little capacity to solve. Making it easier for babies and little kids to stay with family, by contrast, has a track record many millennia long.

Family Welfare

Support for homemaking is also likely to benefit the family as a whole. This author interviewed several current homemakers (as well as parents who wished they could stay home) and quotes from these interviews, which included moms in Ohio, Oklahoma, and upstate New York, are incorporated throughout this paper. Mothers who stayed home with their kids found their role as homemaker to be the cornerstone of their family life—benefits included eating dinner at home together, flexibility to manage kid sick days and school closures, and lower stress without trying to manage two full-time jobs with young children. They also noted that it allowed for closer connections with in-laws, and more time to care for elderly parents or relatives.

Most importantly, for many families the primary beneficiaries of a homemaker were the kids. The interviewed mothers reported that it allowed for a more relaxed lifestyle for their children, including more time to play, less time in the car (e.g., no shuttling between daycare and home), and more one-on-one time with family members. For some mothers, it also offered the opportunity to homeschool children, or the opportunity to provide extra educational support to children who needed it. One mother who had previously worked in manufacturing noted her family made extraordinary sacrifices for her to stay home with their children (including living with her parents)—but that it was worth it. She said: “I am my kids’ primary caregiver and I am not ready to not be available whenever they need.”1Interview with V.F., stay-at-home mom in upstate New York, conducted Feb. 2, 2022. Another mom made the case even more simply:

Question: What is the big benefit of staying home for your kids?

Answer: They get to stay little.2Interview with E.M., stay-at-home mom in Ohio, conducted Jan. 31, 2022.

The belief that a homemaker allows children more time for childhood is supported by research. Most early childhood experts—while certainly not opposed to play-based preschool—stress that little children benefit from orderly routines allowing for enough time to sleep and play, as well as plenty of time to explore the natural world and self-directed interests. By contrast, a worst-case scenario for a busy two-working parent family could include spending upwards of an hour a day shuttling kids between home and full-time daycare, eating Pop-Tarts for breakfast and McDonalds at night, because there is no time for anything else.

For a scenario of what a two working-parent family can entail, consider the resignation email of a Clifford Chance law firm associate—who was also a mother—which briefly went “viral” in 2012 for describing “A Day in Her Life”.

A day in the life of Ms. X (and many others here, I presume):

4:00am: Hear baby screaming, hope I am dreaming, realize I’m not, sleep walk to nursery, give her a pacifier and put her back to sleep

4:45am: Finally get back to bed

5:30am: Alarm goes off, hit snooze

6:00am: See the shadow of a small person standing at my bedroom door, realize it is my son who has wet the bed (time to change the sheets)

6:15am: Hear baby screaming, make a bottle, turn on another excruciating episode of Backyardigans, feed baby

7:00am: Find some clean clothes for the kids, get them dressed

7:30am: Realize that I am still in my pajamas and haven’t showered, so pull hair back in a ponytail and throw on a suit

8:00am: Pile into the car, drive the kids to daycare

8:15am: TRAFFIC

9:00am: finally arrive at daycare, baby spits up on suit, get kids to their classrooms, realize I have a conference call in 15 minutes

9:20am: Run into my office, dial-in to conference call 5 minutes late and realize that no one would have known whether or not I was on the call, but take notes anyway

9:30am: Get an email that my time is late, Again! Enter my time

10:00am: Team meeting; leave with a 50-item to-do list

11:00am: Attempt to prioritize to-do list and start tasks; start an email delegating a portion of the tasks (then, remember there is no one under me)

2:00pm: Realize I forgot to eat lunch, so go to the 9th floor kitchen to score some leftovers

2:30pm: Get a frantic email from a client needing an answer to a question by COB today

2:45pm: postpone work on task number 2 of 50 from to-do list and attempt to draft a response to client’s question

4:30pm: send draft response to Senior Associate and Partner for review

5:00pm: receive conflicting comments from Senior Associate and Partner (one in new version and one in track changes); attempt to reconcile; send redline

5:30pm: wait for approval to send response to client; realize that I am going to be late picking up the kids from daycare ($5 for each minute late)

5:50pm: get approval; quickly send response to client

6:00pm: race to daycare to get the kids (they are the last two there)

6:30pm: TRAFFIC with a side of screaming kids who are starving

7:15pm: Finally arrive home, throw chicken nuggets in the microwave, feed the family

7:45pm: Negotiate with husband over who will do bathtime and bedtime routine; lose

8:00pm: Bath, pajamas, books, bed

9:00pm: Kids are finally asleep, check blackberry and have 25 unread messages

9:15pm: Make a cup of coffee and open laptop; login to Citrix

9:45pm: Citrix finally loads; start task number 2

11:30pm: Wake up and realize I fell asleep at my desk; make more coffee; get through task number 3

1:00am: Jump in the shower (lord knows I won’t have time in the morning)

1:30am: Finally go to bed

REPEAT

As Erika Christakis explained in her influential book, The Importance of Being Little, a “fuller assessment of child development” should include the following questions:

Does the child have room to make independent choices and take risks? Can he find ways to slake his natural curiosity? Is he talked and listened to? Do we give him the space to be quiet with his own thoughts and experience life at a child’s pace? And on a more-down-to-earth level: do little children get enough sleep and time to play?

For many families, having a parent at home would make it easier to answer “yes” to these questions.

Making it easier for American families to have a homemaker may also help alleviate anxieties among women and men considering whether to have a child (or whether to have another child). For example, a 2013 Pew poll indicated that: “Roughly three-quarters of adults (74%) say the increasing number of women working for pay has made it harder for parents to raise children.” Similarly, an extensive study conducted by the Institute for Family Studies found that in developed countries, the more families prioritized career over families, the fewer children they were likely to have. The same study also found that individuals who believed strongly that one parent should not work outside the home had higher fertility ideals than those who prioritize careers.

National Welfare

Finally, an increase in homemaking would have wider effects on social cohesion. For instance, homemakers build closer connections with neighbors and have greater capacity to volunteer. As David Brooks observed in The Nuclear Family Was a Mistake, much of the “togetherness” of the 1950s and early 1960s was made possible by having a mother at home. While rightly criticizing the many downsides of that period’s gender norms, Brooks shows how social cohesion relied upon mothers running coffee hours and arranging community barbeques, while children were free to play throughout the neighborhood because parents could be sure of a watchful eye by whatever neighboring mother happened to be around. Contrast these busy, lively residential neighborhoods of the past with what happens in many American suburbs these days: families drop their children off at daycare, remain outside the house all day, and come home only in the evening, too exhausted to do anything but prepare for doing it all again the next day.

Encouraging homemaking does not mean returning to a 1950s-style society in which mothers generally are expected to stay at home throughout their adult lives, and fathers are solely responsible for earning a family’s income. To the contrary, it means updating policy to reflect how many families already choose to organize their lives and many more say they want to. For instance, in 21st-century America, both men and women may be homemakers, although statistically women are far more likely to stay home to care for children. In many families, both parents will work, and nothing should prevent them from doing so. In some cases, homemakers will have advanced degrees or professional certifications; many will transition in and out of the workforce depending on caregiving needs. Increased lifespans mean greater opportunity for careers after homemaking, but also that special attention should be paid to preparing homemakers for their own retirement or times in which they themselves will need to be cared for.

B. Situating the Homemaker

Crafting coherent and equitable policy to support homemakers requires a political conception of what the homemaker is doing. Caring for children, home, and a family is certainly work, of a type requiring significant skills and personal qualities, including: time management, empathy, appropriate child discipline, dedication, and creativity. But homemaking is fundamentally an act of love and cannot be valued economically on the basis of a price, willingness to pay, or the cost of inputs. Homemakers do not earn a wage, pay taxes on wages, or directly contribute to social insurance programs. And homemaking is viable only as a complementary function within the larger economic unit of the family. One cannot simply put out one’s shingle as a homemaker, nor support a family through homemaking alone. Likewise, what a homemaker does “produce” is “consumed” by the family, akin to a gardener growing vegetables for the dinner table rather than a farmer bringing a crop to the market.

This paper therefore rejects the position that homemaking should be thought of as market labor, treated as part of the larger formal economy, or compensated through a “caregiving wage”—that is, a direct wage from the government to mothers and fathers who stay home to care for children. It also ignores the debate over child allowances or other family benefits, which may have merit, but are connected to the economic wellbeing of the family unit, without reference to the presence or status of the homemaker.

Likewise, questions about how best to support single-parent families and people engaged in other types of caregiving are outside the scope of this paper. Public policy doubtless has a useful role to play, but the goals and tradeoffs will be different ones. Failure to recognize the homemaker as unique, and deserving of unique support, is exactly what has led to the present problem and what policymakers should seek to redress.

II. Government Entitlement Programs and Regulations

A number of different government entitlement programs fail to serve homemakers adequately and require reform. These include: (1) Social Security retirement benefits; (2) Social Security disability coverage; (3) Medicare; and (4) Affordable Care Act Marketplace subsidy rules for one-income families. The first three failures emerge from Social Security’s model for earning credits, which overlooks homemakers in an era when many homemaking moms and dads go in and out of the workforce over the course of their lifetimes.

A. Credit Toward Social Security Benefits

Under the current Social Security program, a worker earns “credits” based upon yearly earnings. For example, in 2022, a worker may earn one credit for every $1,510 in eligible earnings. No more than four credits can be earned each year. A worker must have at least 40 total credits—that is, ten full years of eligible work history—to qualify for Social Security retirement benefits. In addition, the total Social Security benefit at retirement is based on a worker’s highest 35 years of earnings. Put another way, a worker is entitled to a higher Social Security retirement benefit payment the longer he or she works and the more he or she earns—but must work for at least ten years to receive any benefit based on his or her own work history.3There is also a maximum Social Security benefit, but that is unlikely to be relevant for most stay-at-home parents.

As a result, homemakers without a work history do not receive any Social Security benefit at retirement based on their own work. The Social Security system does, however, have a spousal retirement benefit—meaning a homemaker might receive a benefit based on a spouse’s work history. The maximum that a homemaker may receive is half of a spouse’s retirement benefit. The benefit is for married couples, but a divorced spouse may also receive a spousal benefit payment from Social Security if the marriage lasted at least ten years.4Specifically, there are no credits available to couples who are not married/are not in a civil union (the rules for civil unions are complex, and outside the scope of this paper). There is no Social Security benefit available to couples that have children together but never married. In the event of a working spouse’s death, the homemaker spouse will be entitled to a widow/widower benefit. However, that benefit cannot be received in combination with the spousal benefit.

To illustrate this, take an example of two married parents, “Mom” and “Dad.” If Mom stays home to take care of their children (and has no work history), and Dad has a $1,000 monthly Social Security benefit at retirement, Mom may be entitled to up to $500 per month at retirement age as her spousal benefit, giving the family a joint monthly benefit of $1,500. If Dad dies before Mom, Mom may receive a $1,000 monthly benefit at his death as her “widow benefit.” However, she will not receive her own $500 spousal benefit in addition. This means at Dad’s death, the monthly family benefit will drop from $1,500 (when Dad was alive) to $1,000 (when Mom is a widow).

Unlike many other OECD countries, the United States has no system of “caregiver credits” for parents who stop working for a period of time to care for children at home. The format of these caregiver credits varies significantly by country. For example, in France, parents can receive:

- A credit at minimum wage for the homemaker for the first three years of a child’s life (which is particularly designed to benefit working-class mothers who drop out of the workforce entirely for some number of years to care for children, and then return to work);

- Reduction of the total number of quarters a caregiver must work to qualify for a government retirement benefit (designed to benefit mothers of all incomes who return to the workforce after caring for young children); and

- A pension bonus for multiple children (designed to benefit parents who have three or more children).

Germany and Sweden also offer caregiver credits for parents caring for very young children at home. These “caregiver credits” are structured differently based on policy goals. In general, they accrue only during the first few years of a child’s life, not only to allow a mother or father to stay home when children are very young, but also to encourage parents to re-enter the workforce once their children are no longer infants or toddlers. However, a pension bonus for parents who have a third or fourth child may be designed to increase fertility rates by encouraging families who already have children to have another.

In the United States there is no system of retirement caregiver credits—nor any bonus in government retirement benefits for having additional children. While the Social Security spousal benefit does in practice provide a retirement benefit for married mothers who stay home to raise children, it was adopted in 1939. The current structure of the benefit is poorly calibrated to workforce patterns in 2022, in which many homemakers move in and out of the workforce based on their caretaking responsibilities. The current Social Security retirement benefit system seems to envisage a society in which the breadwinner works full-time until retirement, and the homemaker never works at all—which is generally not the case today.

To illustrate this point, let’s return to our example of Mom and Dad. Instead of saying Mom never worked, let’s now say that Mom does have ten years of work history, because she worked for a few years before having children and then re-entered the workforce after her kids left the house. Based on those ten years of work, Mom would be entitled to her own Social Security Retirement benefit. However, because she has not worked the full 35 years on which Social Security is calculated, her own retirement benefit is relatively low. She may be better off taking her spousal benefit—which means she gets no benefit (under Social Security) from having worked and paid into the Social Security system. (She can only receive the larger of her spousal benefit or retirement benefit). The 1939 Social Security framework ends up disadvantaging Mom. A system of “Caregiver Credits” would recognize that homemakers today play different roles over time and provide extra support for those who have gone in and out of the workforce.

Changes to the Social Security retirement benefit system could be means- or income-tested. Changes could be particularly targeted to low- or middle-income homemakers, who would significantly benefit from increased Social Security payments after retirement. For instance, a homemaking credit could be tied to a relatively low hypothetical wage rather than to the wage a particular homemaker earned during years in the labor market. Reforms could also ask families or employers to help bear the cost of changes. For example, a working spouse or employer could have the option to voluntarily contribute to the stay-at-home spouse’s Social Security credits.5For example, say Dad earns $85,000 per year in the commercial shipping industry. As a part of his job responsibilities, Dad is away from home for long periods of time. The couple recognizes Dad’s ability to grow in his career is made possible by Mom, who may handle childcare, house cleaning, and other tasks during Dad’s long, required job absences. However, Mom and Dad are not able to voluntarily decide to contribute to Mom’s Social Security credits out of their household income to ensure a secure retirement for them both. Put another way, there is no way for Dad and Mom to pay both Social Security Credits for Dad and then Social Security Credits for Mom. Nor can Dad’s employer agree to match the social security payments to ensure a secure retirement for Mom. In general, the United States in 2022 lacks a comprehensive way for an employer to help support families with a stay-at-home parent prepare for retirement. This point is discussed further below.

B. Disability Coverage

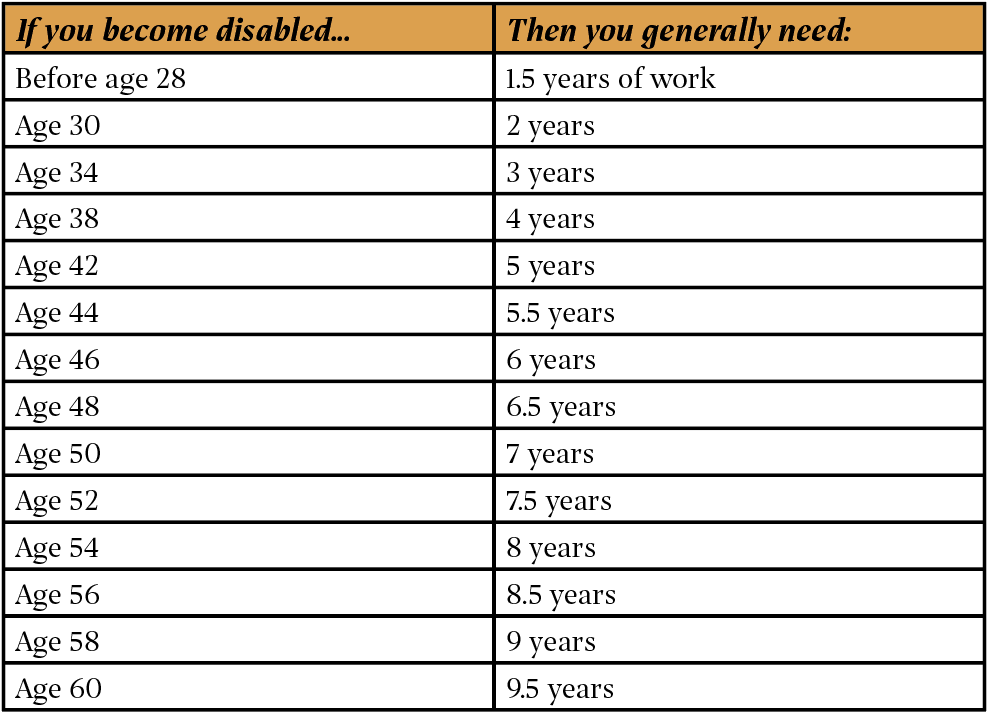

The Social Security credit system also underserves homemakers who become disabled. The federal government provides Social Security Disability Income (“SSDI”) to disabled workers who: (1) have the required number of work credits; and (2) have met the “Recent Work Requirement,” which mandates that an SSDI applicant have recently been in the workforce.

Homemakers may not be eligible for SSDI if they become disabled, due to a lack of work credits. The credit requirement is as follows:

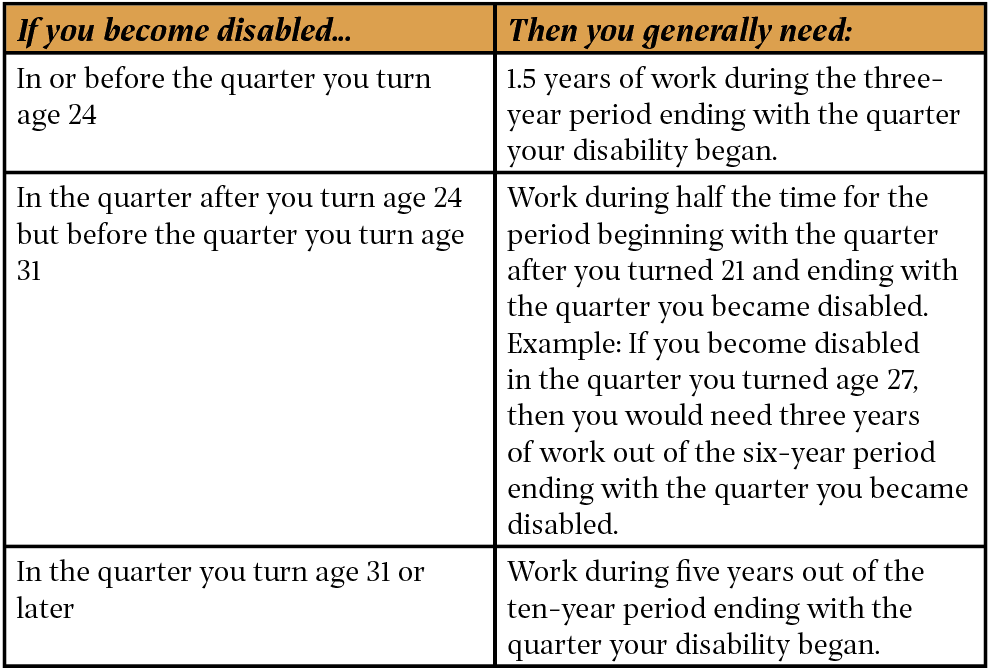

Even parents who have worked in the past may not qualify if they are not working at the time of their disability, because of the Recent Work Requirement. The Recent Work Requirement varies by applicant based on age, but generally requires that the disabled worker have participated in the workforce during the majority of the past ten, six, or three years (depending on the age of the applicant). The Recent Work Requirement is as follows:

For example, say Mom worked full-time for two years between ages 19 and 21 (paying into Social Security during that time), and then left the workforce to care for her young children between ages 22 and 29. She would not be eligible for SSDI if she became disabled at age 31 due to the “Recent Work Requirement.” This is despite paying into Social Security for two years, and then spending years raising young children (who will almost certainly pay into Social Security themselves one day). In theory, Mom could be covered under an alternative program for disabled Americans, called the Supplemental Security Income program (“SSI”). SSI pays out a monthly allowance to disabled individuals who have very low incomes. In practice, unless the family was impoverished, a homemaker in a household with a working breadwinner would likely be unable to qualify for SSI coverage.

Private disability insurance policies also serve homemakers poorly, as they generally serve as income replacement policies. They are typically issued through an employer and are designed to replace a percentage of an employee’s paycheck. For example, an employer may offer a package of benefits to an employee that includes a short-term disability policy (designed to replace 80% of income), and then a long-term disability policy (intended to replace 60% after the short-term policy ends). This structure, obviously, does not cover homemakers who do not earn a wage. Some insurers do have disability policies for homemakers, designed to cover the extra costs a household will incur if a homemaker becomes disabled, but they are uncommon.

This leaves a doughnut hole of coverage for homemakers who become disabled, which ultimately originates from the highly valuable but not market-valued nature of homemaking. Returning to our example, while the family would certainly incur extra expenses should Mom become disabled (including childcare costs, replacing Mom’s labor in other areas, and potentially to provide care for Mom), their household assets likely would be too large for SSI, and if Mom’s work history is not sufficient for SSDI, no government support would be available for this family—nor is it likely that Mom has a private disability insurance policy. The system of Caregiver Credits discussed above would help to address the SSDI issue. Further, as discussed below, private employers and insurers could also help by offering expanded benefits packages with insurance policies covering homemakers who become disabled.

C. Medicare

Most Americans become eligible for Medicare at age 65. To receive Medicare Part A without paying premiums—that is, to receive “premium-free” Medicare Part A—a participant needs a sufficient work history of paying Medicare taxes. As with Social Security, a participant usually must work about ten years to be eligible for premium-free Medicare Part A. Homemakers without a work history can be eligible for premium-free Medicare Part A when they turn 65 if their spousehas sufficient work credits. Just as with Social Security retirement, a homemaker can also be eligible through the work credits of a divorced spouse.

However, the working spouse must be at least 62 to access this benefit. As a result, if the homemaker is more than three years older than the working spouse, the homemaker may not be eligible for premium-free Medicare Part A at age 65, and the cost of purchasing Medicare Part A without a work history can be hundreds of dollars per month. One solution to this problem would be coverage under employer health plans for homemakers in this situation (if the breadwinner spouse is still working). As discussed below, employers should be strongly encouraged to provide comprehensive health coverage for spouses, including when a homemaker spouse is not eligible for premium-free Medicare Part A. The federal government could also close this doughnut hole by allowing a homemaker spouse in this situation to be eligible for premium-free Medicare Part A or alleviate the problem through Caregiver Credits.

Issues also arise if the homemaker is younger than the working spouse. Specifically, if the homemaker has not yet turned 65 at the time of a spouse’s retirement at age 65, he or she may lose health care coverage under the spouse’s former employer’s group health plan. Some employers have retiree health benefits for spouses—but many do not.

Take the example of Dad, a homemaker who is five years younger than Mom. When Mom retires from employment at 65, the family may have a five-year window in which they must purchase an individual health insurance policy for Dad. Such policies can be very expensive and may cover fewer services than would be available on Mom’s health insurance plan when she was working (or through Medicare, if Dad were eligible). This can result in families staying in the workforce longer than they desire, with Mom continuing to work until age 70 (when Dad turns 65 and becomes Medicare-eligible) just to ensure Dad has good health insurance coverage. Better retiree health coverage from employers could help close this gap, as could changes to Medicare eligibility rules, or a more generous subsidy in the Affordable Care Act (ACA) Marketplace for someone in this situation.

“My husband makes $52k/year which in our state puts us over the income threshold for Medicaid. His job was charging us $600/mo just for me alone to put me on his health insurance, which is not nice or fancy insurance by any means. Certainly not worth $600/mo for a single person. We don’t qualify for discounts on the Marketplace because they only consider the price for HIS insurance, not spouse or family insurance. I finally settled on having 2 different insurances, husband and baby on job insurance, myself on Marketplace insurance. Which is not really ideal because now we have 2 deductibles to meet, but it was the only way to stay under $500/mo for health insurance. It’s called The Family Glitch: single income but too rich for Medicaid, job doesn’t offer affordable family insurance, don’t qualify for tax credits on the Marketplace.” —M.C., mom in a single-earner family

D. The ACA Marketplace’s “Family Glitch”

Beyond the Social Security program, other public subsidies also disfavor families with a homemaker. Most notable is the structure of ACA Marketplace subsidies, available for those who have no employer-sponsored health insurance and who are ineligible for Medicare or Medicaid. A subsidy is available for workers who do have access to employer-sponsored health insurance if the premiums for that insurance are deemed too high to be affordable. Under current rules, a worker who would have to pay more than about 10% of household income for the premium on an employer-sponsored plan is eligible for a subsidy in the ACA Marketplace.

The problem is that this calculation is based only on the premium for insuring the individual worker, not the entire family. Many single-earner families thus face what is called the “Family Glitch,” which largely impacts middle- or working-class families with one employed spouse. These families have a household income that is too large to qualify for Medicaid but are left unable to afford health insurance for the whole family. Let’s say Dad works at ACME Shipping, which offers a health insurance plan to its employees. Under the ACA, Dad can qualify for a marketplace subsidy if the cost of ACME’s health insurance plan is so high that it requires Dad to spend more than 10% of his income on the premium. But if his own coverage would only cost 5% of his income, while covering his whole family would cost 20%, he is out of luck.

The Family Glitch may be addressable by rulemaking at the U.S. Department of Labor, rather than requiring new legislation. The Biden administration has proposed a regulatory change that would help to address this situation by allowing a family to receive a marketplace subsidy unless the employer offers “affordable” health insurance to the entire family. But because the Biden administration’s interpretation would be at odds with the Obama administration’s prior interpretation (which created the “Family Glitch”), the proposed rule could face legal challenge—or subsequent reversal by a future administration. Congressional action is preferrable. And, as discussed further below, encouraging employers to offer affordable health insurance to the entire family should be an important goal for policymakers.

III. ERISA and Related Employee Benefits Issues

In recent years, employers have—voluntarily or as required by law—modified employee benefit offerings to respond to modern social concerns. Examples include: adding Environment, Social and Governmental (“ESG”) indices to retirement plans in response to climate change concerns; requiring welfare benefit plans to allow naming members of a same-sex couple as beneficiaries; providing coverage of health care benefits for transgender surgeries; and requiring health care benefits for certain types of IVF or other similar fertility treatment.

Policymakers should modify federal regulations so that employers can likewise expand their employee benefits offerings to better protect families with a homemaker. This should be in the interest of both employees and employers. Many jobs are so demanding that they essentially require a homemaker spouse if the couple has children. Jobs with significant travel requirements and long required periods away from home are obvious examples: long-haul trucking, military deployments, offshore oil drilling, and so on all place such significant demands on employees that families with small children may struggle without a homemaker. Similarly, jobs that require 24/7 availability from their employees may also require a homemaker spouse to appropriately care for small children. Offering jobs that are attractive to families with a homemaker might also be a useful recruiting strategy for employers, and breadwinners should have the opportunity to negotiate with their employers for appropriate family support. Employers could advertise themselves as “a great place to work for families with a homemaker,” just as many of them currently take pride in advertising themselves as “a great place for working moms” or “a great workplace for parents.”

This paper proposes modifying relevant statutes and regulations so that employers may offer expanded benefit packages to families with a homemaker in the following areas: (1) retirement benefits, (2) health care benefits, (3) disability benefits, and (4) student loan repayment programs.

“Knowing what to do when you get close to retirement . . . is an issue for a stay-at-home [parent] . . . You are kind of winging it.” —B.C., stay-at-home mom in Oklahoma

A. Retirement Benefits

Under the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA) and the current Internal Revenue Code (“IRC”), most contemporary private retirement savings plans are “defined contribution plans,” typically either 401(k) or IRA plans, into which a worker and an employer can contribute tax-advantaged funds. A 401(k) plan is offered by a company, while an IRA is an individual retirement account.6Somewhat confusingly, a small employer can also offer what is called a “SIMPLE IRA plan,” which has aspects of both a 401(k) and a traditional IRA. These plans are designed for workers earning income in the labor market, to the disadvantage of homemakers and their families.

A 401(k) or IRA account is held in a worker’s name. The worker can contribute $20,500 (or up to $27,000 with so-called “catch-up contributions” at or after age 50) to a 401(k), or $6,000 to an IRA ($7,000 with catch-up contributions). A homemaker has no access to a 401(k). A working spouse can contribute to a “Spousal IRA” for a homemaker spouse, but the annual limit is currently $6,000 (or $7,000 with catch-up contributions at age 50 or older) and there are income phase-outs for Spousal IRA availability.

As a result, working families with one breadwinner and one homemaker do not have as much tax-sheltered space available to them in retirement accounts as families with two working parents. Let’s say Dad earns $150,000 at the peak of his career when he is 55 and Mom is 50. He has access to a 401(k) plan through his job. The family can therefore save $27,000 annually in his 401(k) and then also put $7,000 into a Spousal IRA for Mom, for total tax-sheltered retirement savings of $34,000. However, if Mom and Dad were both working at jobs with 401(k)s, and each earning $75,000, they would each have $27,000 of tax-sheltered space, for a total of $54,000 for the family.

The current system also disadvantages Mom and leaves her vulnerable in the event of a divorce. Under the current system, Dad’s 401(k) is held in his name—and Mom only holds the title to her own Spousal IRA. This means that Mom will have less money in her own name as she faces retirement. ERISA creates a procedure for a court to issue a Qualified Domestic Relations Order (“QDRO”) in the event of a divorce, which could entitle a non-working spouse to half the retirement assets of the working spouse. But the QDRO process is cumbersome, not least because the relevant rights need to be vindicated through the courts and require an experienced attorney to navigate the process.

In addition, ERISA requires a spousal waiver form to name a beneficiary other than the current spouse for any retirement or other plan benefit (such as a life insurance policy). Consequently, former spouses may need to pursue litigation to obtain their share of retirement or life insurance benefits even if they are entitled to those benefits under a QDRO or divorce decree, particularly if the policy holder has remarried and both an ex- and current spouse are claiming the benefit. Much of the benefit may be eaten up by parties’ attorney’s fees (including attorney’s fees of the insurance company or plan sponsor, which often can be deducted from the policy principal under court rules).

Policymakers should establish a “Family 401(k)” or a “Family IRA.” This would be a jointly held retirement account—similar to a jointly held bank account or house—that allows the family to save for retirement together. A Family Retirement Account (or “FRA”) would provide more tax-sheltered space for families with a homemaker and ensure that in the event of divorce or separation the retirement benefit would have to be distributed equally between the former spouses. An FRA might also simplify matters for widows or widowers, who could simply maintain the funds as invested (depending on plan rules), without having to take a distribution and rolling funds into another account.

An FRA would also offer a number of administrative benefits. A homemaker who goes in and out of the workforce depending on the family’s needs would maintain all retirement savings in the same account, rather than dealing with multiple individual accounts or frequent rollovers. Allowing couples to combine their retirement savings into one account could allow for more efficient savings, including:

- Savings on Administrative Fees: Most retirement plans have an administrative fee that is assessed on each plan. For example, Dad left the workforce to take care of the kids but maintains his 401(k) with his former employer. That 401(k) is likely subject to an annual administration fee. Mom, still in the workforce, also maintains her 401(k), with an annual administration fee. Allowing them to combine their accounts into a single Family 401(k) would enable the couple to pay only one administration fee.

- Saving on Expense Ratios: Similarly, most Plans have lower expenses ratios for larger investment amounts. For example, a Fund may offer ordinary shares for an investor with less than $10K invested, at an expense ratio of 0.10%, but superior shares for an investor with more than $50K invested, at an expense ratio of 0.04%. Allowing couples to combine their savings into one Plan may allow them to save on expense ratios.

Establishing an FRA might also allow employers to better attract and retain talented workers by contributing to the homemaker’s savings and ensuring that homemaker spouses are protected at retirement age. Employers could explicitly recognize the value that a homemaker spouse adds to a working parent’s ability to grow in his or her career, and the fact that the household income is made possible by the entire household (including the stay-at-home parent). An employer match for a Family 401(k) could allow the employer to commit to supporting the entire family, rather than just the breadwinner. In many ways, a Family 401(k) would have many similarities with the old private employer pension system (now uncommon), which usually made explicit provision for an employee’s spouse in the event of the employee’s death.

B. Education Benefits

Recent legislation has authorized employers to repay employees’ student loans as part of employee benefits packages. Previously, an employer could create an “Educational Assistance Plan,” or a Section 127 Plan, that provided for tuition payments for an employee.7I.R.C. § 127(a). Under the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (“CARES”) Act—and extended in the 2021 Consolidated Appropriations Act—an employer can expand a Section 127 Plan or create a new one that reimburses the employee for up to $5,250 paid towards an employee’s student loans, without counting that reimbursement in the employee’s gross income. There are additional special rules that can (in some circumstances) allow private employers to pay tuition for an employee’s spouse—but as yet, no special rules allowing loan repayments for the employee’s spouse. Student loans are often a major barrier to a family choosing to have a homemaker; extending an employer’s ability to help a worker’s spouse repay such loans might be a valuable fringe benefit.

C. Disability Benefits

As discussed above, homemakers encounter a doughnut hole in disability coverage that employers could help to address. While existing law does nothing to preclude insurance companies from offering homemaker coverage or employers from assisting families in finding such coverage, in practice such options rarely exist. Employers should ask insurance companies to develop products that addressing this gap and in turn offer them to employees.

D. Health Care Benefits

While the ACA requires employers to provide health coverage to an employee’s dependents up to age 26, there is no spousal coverage requirement. As a result, some employers offer no health coverage to their employees’ spouses, and others offer extremely poor or expensive coverage. Employers can choose to subsidize the cost of health insurance premiums for their employee, but not for the employee’s family. Researchers have found that employers are far less likely to subsidize family health care than employee health care, especially for low-income workers:

Covered workers on average contribute 17% of the premium for single coverage and 28% of the premium for family coverage[.] The average monthly worker contributions are $108 for single coverage ($1,299 annually) and $497 for family coverage ($5,969 annually) . . . Covered workers in firms with a relatively large share of lower-wage workers (where at least 35% of workers earn $28,000 a year or less) have a higher average contribution rate for family coverage than those in firms with a smaller share of lower-wage workers (35% vs. 27%).

The end result can be that the family would be better off—for health insurance purposes—if the homemaker were not married to the working parent, since he or she would then be eligible for Medicaid.

Problems also occur with employer-sponsored coverage at retirement. Some employers offer retiree health benefits for former employees, but it is less common for employers to offer retiree health benefits for spouses.8KFF, 2021 Employer Health Benefits Survey, at pg. 175. As discussed above, this can leave a homemaker spouse without coverage depending on his or her Medicare eligibility.

Employers should offer comprehensive family health insurance. Unions and employees should bargain for such coverage, and the government should consider both carrots and sticks to advance this goal. Fixing the “Family Glitch” would help, but it does so by taking employers off the hook and providing more government subsidies. Policymakers should also consider mandates requiring employers to provide comprehensive family coverage, including through modifying or better enforcing current non-discrimination tests for family health insurance.

Conclusion

The single-minded pursuit of rising GDP has led policymakers of the past generation to place an emphasis on pushing homemakers into the workforce, abandoning vital elements of their non-market labor and outsourcing other parts to commercial providers whose work gets counted as GDP, too. Unsurprisingly, then, the nation’s structures of social insurance and employment benefits have ignored homemakers’ needs or outright disadvantaged families opting to go that route. As part of a recommitment to family policy that recognizes homemaking’s unique value and places a thumb on the scale in its favor, policymakers should pursue reforms to Social Security, ERISA, and related laws and regulations to support parents making that choice. Employers should recognize that no form of “corporate social responsibility” is more important than helping their workers build the family lives that they want.

Recommended Reading

Home Building

Public Policy for the American Family

Home Building Survey Part II: Supporting Families

American attitudes about family structure vary widely, but most families see a full-time earner and a stay-at-home parent as the ideal arrangement for raising young children.

The Family Income Supplemental Credit

This paper presents the case for a per-child family benefit that would operate as a form of reciprocal social insurance paid only to working families.