RECOMMENDED READING

Japan has announced newly defined restrictions on foreign investment, which at face value, seem to violate the provisions of the World Trade Organization agreement. Of course, Tokyo has crafted these restrictions on the vague grounds of “national security”, which is likely to take on a substantially different meaning in light of the coronavirus pandemic. Hence, the country is unlikely to face any serious challenge from other WTO members.

Nor should it. Traditional supporters of the old globalized world order, notably the Financial Times, have predictably criticized the Japanese government’s framework as “protectionist”, as if this charge in itself constitutes grounds to discontinue the policies. But historically, Japan has never allowed national interest to be defined by market fundamentalist/neoliberal considerations alone.

Even the FT has conceded that COVID-19 has “bludgeoned the comforting assumption that the market will always find a way to deliver whatever is needed. It has distended the list of which businesses — from makers of paper masks and rubber gloves, to biotech start-ups and producers of specialist chemicals — might, from now on, need to be ringfenced as a matter of policy.”

What kind of market cannot ramp up toilet paper production, for instance? Not to mention more serious things like personal protective equipment (PPE) and test swabs? Didn’t the champions of market fundamentalism tell us that the consumer always gets what he/she wants? Put another way, if an industrialized country is unable to supply itself in an emergency, is it truly industrialized? National security dimensions of economic planning that have receded and were dormant for decades are therefore back in play in Japan.

From Tokyo’s perspective, the silver lining of the coronavirus is that it is enabling its government to reorient policy in a direction to which the country has long been culturally and historically predisposed. Before they were “tutored” by their counterparts in Washington, policymakers in Tokyo took the view that a viable industrial ecosystem represented something beyond a mere corporate profit & loss statement. Rather, they saw the economy in more holistic terms, comprising the sum of its companies, its tangible assets, intellectual property, but also the well-being of the labor force, and broader social cohesion. Even after undertaking US mandated reforms under considerable pressure from the American government in the 1980s, Japan never fully embraced the “downsize and distribute” regime of American shareholder capitalism, in which the labor force is downsized, domestic operations are discontinued, and the cash retrieved from these processes is distributed rather than retaining and reinvesting in developing the economy’s productive capabilities.

Hence, the Japanese government’s plans today to prioritize domestic reinvestment, and reduce key supply chains that currently depend on China. The endpoint evokes the older “Toyota City” model, characterized by suppliers clustered in a tight geographical area to supply product, as opposed to companies that span far-flung parts of the globe, weakly connected by unpredictable logistics and supply chain links.

Likewise, in prioritizing domestic industries and investment, Japan’s policy makers understand that there is little point in devising an economic reconstruction plan if there is nothing domestic left to reconstruct. Absent local content requirements, the benefits “leak” to the rest of the world.

The US is particularly vulnerable in this regard, given the extent to which its industrial ecosystem has already been denuded. Absent a viable domestic manufacturing capacity, a public works program for the US risks becoming a public works program for the rest of the world with minimal benefit accruing to the average American worker. Japan wants to avoid this scenario by tightening the investment screening regime around a dozen vital sectors (e.g., power generation, military equipment, computer software, high tech).

No doubt the high priests of free trade and globalization will argue that there are significant cost premiums associated with prioritizing domestic production, redomiciling sources of supplies or carrying more safety inventory. Many allege that such inefficiencies will recreate the conditions of the stagflationary 1970s. But the champions of globalization have persistently failed to acknowledge the substantial social and economic costs that our workforces have been experiencing for years even before the onset of COVID-19. The brutal consequences of these policies have been particularly laid bare today and are worsening daily. Ignoring them, or working to reconstruct a status quo ante, is a policy dead end. Happily, Japan is moving in a different direction via a combination of domestic content, regionalism, and cohesive industrial policy. This is a very compelling policy matrix that the rest of the world would do well to emulate.

Recommended Reading

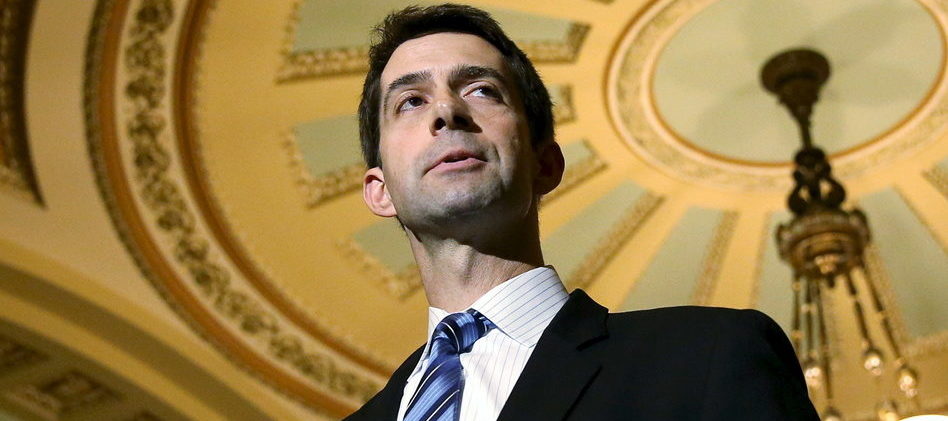

America Cottons on to Industrial Policy Again

Recently, I suggested that the United States would do well to emulate some aspects of China’s economic development model, largely on the grounds that this still constituted the optimal route to reindustrialization. If done correctly, reindustrialization can provide a key means of generating high quality jobs in the U.S. and a corresponding break from today’s prevailing market fundamentalist model characterized by precarious employment prospects, wage stagnation and the loss of many of the attributes long associated with a prosperous and stable middle class.

Coalition Letter: Outbound Investment Restrictions

As the FY2024 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) moves through conference committee, we write to urge Congress’s support for security-related restrictions on outbound investment of American capital to the People’s Republic of China (PRC).

American Compass and Heritage Foundation Lead Coalition Letter Urging Outbound Investment Restrictions

FY24 NDAA should maintain disclosure requirements and restrict U.S. capital flows to China