RECOMMENDED READING

I read “Searching for Capitalism in the Wreckage of Globalization” with more frustration than surprise. Oren Cass’s argument consists, roughly speaking, of two parts. The substance of both parts unfortunately reflects a number of fundamental misunderstandings.

The first part of Mr. Cass’s argument is that the entire economics profession has either misread or misinterpreted a sentence in Adam Smith’s An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, and that it has built the case for free trade from that alleged misreading or misrepresentation. This is simply and fundamentally not true.

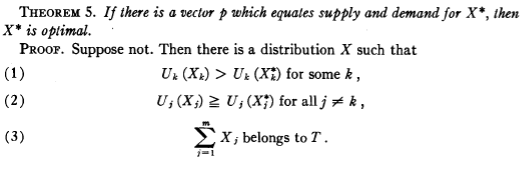

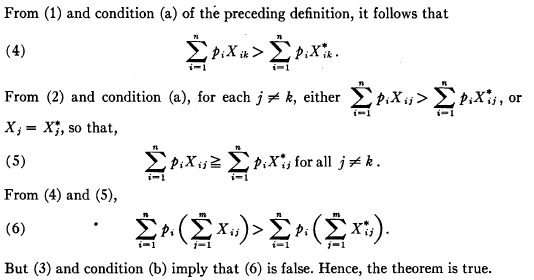

Modern economic theory in general, and trade theory in particular, is not built on quotations from 18th-century books. In fact, a typical proof of the first fundamental theorem of welfare economics—the closest thing to a formalization of Smith’s invisible hand—looks as follows:

The thing to note here: No Smith or Ricardo quotes to support the optimality of the free-market equilibrium. The role their works play for modern economists is that of sources of both inspiration (rarely) and rhetorical flourish (more frequently). Now, I agree that history of thought is interesting even in the absence of current applications, but it does highlight how completely unrelated Mr. Cass’s arguments are to the typical modern case for free trade.

(And in fairness to the economics profession, surely you wouldn’t expect mathematicians to master their craft by reading Leibnitz, or biologists by reading Darwin.)

Now, the optimality result above relies on assumptions that may not be realistic. But those assumptions are explicitly spelled out in the article I took the exhibit from, and much modern work in microeconomic and trade theory has gone into exploring the consequences of relaxing them. For example: In the absence of retaliation, a sufficiently small tariff increase starting from a situation of free trade will improve national welfare.

The second part of Mr. Cass’s article then takes the allegedly misread or misrepresented phrase by Smith (“By preferring the support of domestic to that of foreign industry…”), and claims that it not only undermines the case for free trade, but also justifies a system of capital controls. This attempt misses the point on various levels.

First, the typical modern case for free trade does not rely on even the existence of capital or production, and it holds (more trivially, in fact) in a so-called endowment economy.

Second, free movement of capital and labor can lead to even better outcomes than free trade alone, as Ricardo, ironically, understood and explained in a section quoted by Mr. Cass. This can happen through risk-sharing, through learning by importers and exporters, from the ability of workers to find their niche in a foreign land. I say “can,” because of course many people like to live and invest where they were born, surrounded by familiar faces, smells, streets, and sounds. And a system of relatively free movement of capital and labor obviously allows that!

In fact—and this is the third important misunderstanding I was surprised to encounter—a classic result in modern international economics is that investors disproportionately choose to invest in their home countries. This runs counter to the claims in Mr. Cass’s article that capitalists are forced to invest abroad under our regime of relatively free capital flows. To the extent that Smith and Ricardo believed home-bias investment was a necessary requirement for the case for free trade to hold—which again, I would not concede—they need not fret!

Fourth and finally, much of the second half of the article suggests that American capital has fled Ohio for China. In fact, the U.S. net investment position is deeply negative. This means that overseas residents have invested more in the U.S. than U.S. residents have invested overseas—70% of GDP more. If anything, this means that the U.S. capital stock would be smaller under Mr. Cass’s preferred policies, rather than greater, because overseas residents currently finance a good chunk of it. That in turn completely undermines his central argument even if we accept his theoretical premises, which we should not.

As a closing thought, I will say that the substance and tone of the article make me even more concerned than I already was about the national-conservative intellectual climate. Let me explain.

First, on substance: It is worrisome that the national-conservative movement is now so isolated from America’s mainstream intellectual life that its leading thinkers struggle with relatively well-known facts about economics and the economy in the manner highlighted here.

Second, the discovery Mr. Cass thought he had made led him to consider a potential “global conspiracy.” What he thought he had discovered was, so he claimed, “enough to send one searching for the meeting minutes from whichever Illuminati subcommittee had jurisdiction.” This is not a normal response. The normal response would have been to assume he must be missing something, and to read a book on the intellectual history of free trade like Doug Irwin’s Against the Tide (which includes the full quotation Mr. Cass believes to have uncovered, for what it’s worth), or to reach out to someone with advanced training in economics. It is not a normal response, but it is an all too common one.

Recommended Reading

It’s Time for a Neoclassical Economic Reckoning

Oren Cass’s essay demonstrates how the advantages of industrial policy, apparent to some of the founders of economics and foundational to the success of the United States, were carefully airbrushed out by advocates of free trade in the 20th century.

Weighing In

Commentators and policy analysts respond to our analysis of globalization and proposals to restore balance to the American economy

Globalists Finally See Reality

When the former high priests of globalization admit it’s not working, the time has come not only to ask why they’ve changed their minds, but also why they were so wrong for so long. Oren Cass’s exposé of the abuses of classical economic theory offers a valuable starting point. But the problems lie even deeper and extend much further.