American labor law has become worse than useless: a lower share of the private-sector labor force is organized today than before the National Labor Relations Act was passed in 1935. The time has come for an entirely new model.

RECOMMENDED READING

America’s system of organized labor is a failure. The 6.2 percent of private-sector workers represented by unions today is not only a shadow of the one-third represented in the mid-20th century, but also a decline from the level of representation before the passage of the National Labor Relations Act in 1935. The American legal framework for labor relations has failed workers, employers, and taxpayers alike, creating a vicious and unsustainable cycle of waning worker bargaining power, falling wages, and growing state-administered redistribution.

What Killed the American Private-Sector Union?

What accounts for the steep decline of unionization?

Labor arbitrage is routinely offered as a reason for organized labor’s decline, and in certain sectors, like manufacturing, geographic labor arbitrage has been an important factor. For instance, firms may transfer production to jurisdictions hostile to unionism either in the U.S., like the anti-union “right to work” states, or abroad, like China, Vietnam, and Mexico. The movement of entire manufacturing supply chains to the American South or overseas has forced many formerly unionized workers and their descendants into low-wage, non-union service sector jobs.

Firms also practice labor arbitrage by importing legal and illegal immigrants or guest workers as substitutes for American workers with labor rights, including the right to organize. Employers in low-wage sectors like agriculture, construction, meat-packing, hotel maid service, and fast-food restaurants, as well as some high-wage sectors in Silicon Valley, have used illegal immigrants or legally authorized guest workers to evade U.S. labor laws and weaken unionization.

The long decline of American organized labor is also often blamed on the Taft-Hartley Act of 1947. Among other obstacles to unionization, the Taft-Hartley Act authorized state right-to-work laws that allow workers to refuse to join a union or pay dues to a union, as a condition of employment at a unionized business. Today twenty-seven states, concentrated in the South, have right-to-work legislation.1“Right-To-Work Resources,” National Conference of State Legislatures.

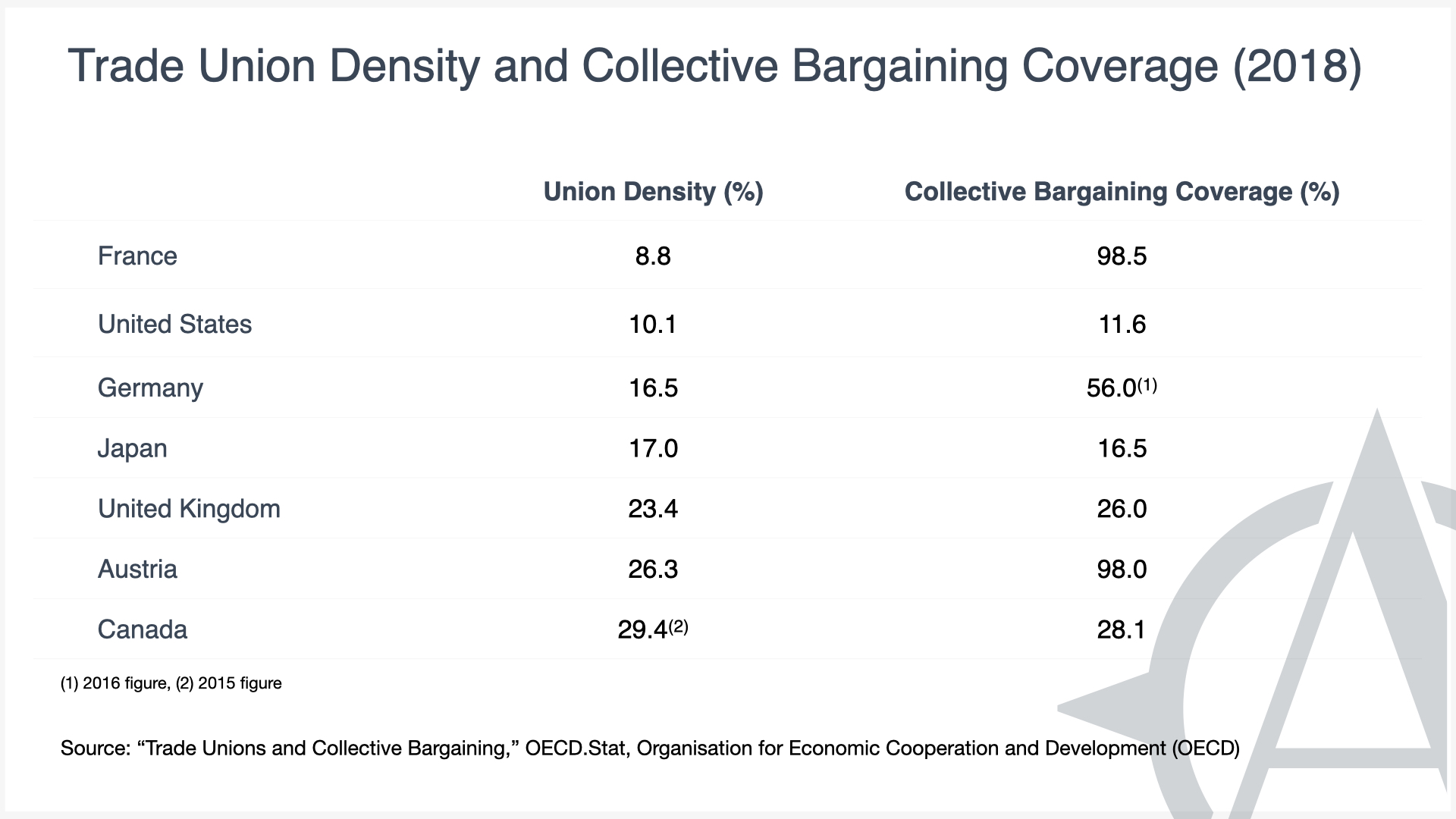

But labor arbitrage and right-to-work laws, while important, cannot be the predominant factor in union decline. After all, offshoring and high levels of immigration have taken place in other Western democracies with voluntary union membership without producing comparable declines in labor union membership (union density) or the percent of the workforce covered by union-negotiated agreements with employers (collective bargaining coverage). Trade union density and collective bargaining coverage vary dramatically among countries, depending on national labor laws.

The main difference among national labor systems involves the presence or absence of “sectoral” bargaining, in which one or more unions negotiate with multiple employers to determine wages, benefits, and/or working conditions for an entire industry or profession. Low levels of union membership can be accompanied by high numbers of workers covered by union-negotiated agreements, as in France, where 98.5 percent of workers are covered by sectoral agreements even though only 8.8 percent of French workers belong to unions.

The alternative to sectoral bargaining is “enterprise-based” bargaining, in which unions attempt to unionize a single firm or sometimes only one of several workplaces within a single firm. The enterprise-based system creates a number of destructive incentives. In the absence of industry-wide standards, individual firms have incentives to avoid unionization, to prevent being undercut by rival firms that can charge lower prices because of their cheaper, non-union labor. From the perspective of workers, unionizing a single company or a single worksite can be a Pyrrhic victory if it incentivizes the company to close the site or to go out of business altogether.

The decentralized, enterprise-based system also creates opportunities for corruption that would be easier to expose and punish in a more centralized system. As the late Robert Fitch observed:

Like feudal vassals, local leaders get their exclusive jurisdiction from a higher-level organization and pass on a share of their dues. The ordinary members are like the serfs who pay compulsory dues and come with the territory. The union bosses control jobs — staff jobs or hiring hall jobs — the coin of the political realm. Those who get the jobs — the clients — give back their unconditional loyalty. The politics of loyalty produces, systematically, poles of corruption and apathy. The privileged minority who turn the union into their personal business. And the vast majority who ignore the union as none of their business.2Michael D. Yates, “What’s the Matter with U.S. Organized Labor? An Interview with Robert Fitch,” Monthly Review(March 30, 2006).

The Road Not Taken

A case can thus be made that the seeds of destruction of organized labor in the United States were present in American labor law itself, which favors bargaining at the level of the individual enterprise over multi-employer collective bargaining. With a few exceptions, the American labor system is enterprise-based, with low union density and correspondingly low collective bargaining coverage.

The existing American system of enterprise-based bargaining is an accident of history. In 1933, Congress passed the National Industry Recovery Act (NIRA), modeled on tripartite business-labor-government arrangements during World War I. The main purpose of the NIRA was to allow what became the National Recovery Administration (NRA) to oversee the establishment of industry-wide codes of fair competition, as long as these did not encourage monopoly, and to formulate industry-specific wages and hours laws. Section 7(a), which allowed workers to unionize and engage in collective bargaining, triggered a wave of labor organizing.

Claiming that it represented an unconstitutional delegation of power from Congress to the executive branch, the Supreme Court struck down the National Industrial Recovery Act on May 27, 1935.3A.L.A. Schechter Poultry Corporation v. U.S., 295 U.S. 495 (1935). As a partial replacement for the NIRA, Congress hastily passed the National Labor Relations Act (or Wagner Act) a few months later on July 6, 1935. The Wagner Act remains the basis of U.S. labor law. But had the NIRA system survived and evolved, tripartite bargaining in various sectors might be the norm today.

While multi-employer bargaining is permitted under the Wagner Act, both employers and unions must consent to it, making it rare in the U.S. outside of a few industries like professional sports and the hotel industry. To get a sense of what the condition of U.S. organized labor today might be in the absence of both labor arbitrage and enterprise bargaining, we can look at two labor law regimes outside of the Wagner Act system: the Railway Labor Act (RLA) and state wage boards.

Signed into law by Republican President Calvin Coolidge in 1926, the RLA, which today governs airline as well as railroad employees, sought to prevent strikes from disrupting the rail-based transportation system by putting in place an elaborate system of mediation and arbitration that included multi-employer collective bargaining.445 U.S. Code Chapter 8—Railway Labor. In the most recent 2020 national bargaining round in the railroad industry, the National Carriers’ Conference Committee, representing 37 railroads, including CSX and Union Pacific, negotiated with 12 rail unions that represent roughly 125,000 employees, including the International Association of Sheet Metal, Air, Rail, and Transportation Workers (SMART-TD). the Transportation Communications International Union (TCU), and the American Train Dispatchers Association (ATDA).5“Who Are the Parties? Thirty Seven Railroads and Twelve Unions,” National Railway Labor Conference.

The contrast between industries covered by the Wagner Act and those covered by the Railway Labor Act is striking, in terms of both union density and coverage. In 2018, 81 percent of subway, train, and rail workers were covered by union agreements, and 77 percent were unionized. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), even though the typical entry-level credential of a railroad worker is a high school diploma or equivalent, the median pay of railroad workers in 2018 was $61,480 per year. In contrast, in transportation and warehousing, defined by BLS as “private-sector industries with high unionization,” only 16.1 percent of workers were unionized. Truck drivers make $47,000 a year, and school bus drivers only $34,820.6“Transportation and Warehousing: NAICS 48-49,” Industries at a Glance, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

In addition to operating under a labor law regime that permits and encourages multi-employer bargaining, railroad and airline workers are protected from the threat of geographic labor arbitrage by their employers. Unlike factories, railroads and subways cannot be offshored, and for national security as well as economic reasons, the U.S. government maintains a domestic airline industry. While legal permanent residents can work in these industries, railroad and airline workers cannot be replaced by illegal immigrants – unlike many factory, agricultural, and service workers in the U.S. The same immunity to arbitrage helps to explain the relative success of public-sector unions. Their employers are geographically immobile and public sector workers in most cases are protected from being replaced by non-visa guest workers like H-1Bs, to say nothing of illegal immigrants.

Like the Railway Labor Act, state wage board laws provide an alternative to the enterprise-based bargaining of the Wagner Act. Wage boards are government bodies that bring together representatives of labor, employers, and government to set wages, benefits, and working standards for entire industries or occupations.

In the early twentieth century, in the UK and other English-speaking countries as well as the U.S., wage boards were devised as a supplement to trade unions, to be limited to so-called “sweated trades” like piece-work sewing that were low-wage, often dominated by female workers, and difficult to unionize.

A short-lived federal wage board system in the U.S. was created in 1938 by the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA), which established today’s minimum wage, maximum hours, and overtime laws. The FLSA initially created federal wage boards or “industry committees” with tripartite representation of unions, employers, and the public that were authorized to set minimum wages (though not working conditions or benefits) in particular industries. In 1949, however, during a backlash against pro-labor laws led by segregationist Democrats and anti-New Deal Republicans, the FLSA was amended to eliminate the tripartite federal wage boards, except in the cases of Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands.7Kate Andrias, “An American Approach to Social Democracy: The Forgotten Promise of the Fair Labor Standards Act,” The Yale Law Journal 128 (3) (January 2019).

A few states including New York, California, New Jersey, and Arizona have state statutes authorizing tripartite wage boards to set wages or regulations in specific industries that date back to the early twentieth century.8Kate Andrias, “Social Bargaining in States and Cities: Toward a More Egalitarian and Democratic Workplace Law,” Harvard Law School Symposium: 6, note 33. Other states allow the executive branch, following public hearings, to regulate wages or hours in specific occupations.9Ibid., 6, note 32. Using a law passed in 1933, for instance, the State of New York convened a wage board to raise wages in the fast-food industry to $15 an hour in 2015.10Katie Hope, “New York state to raise fast food minimum wage,” BBC (July 23, 2015). New York also authorized a wage board for farm workers in 2019.11Senate Bill S6578, The New York State Senate (2019). But most state wage boards have laid moribund for decades.

The Worst System, Except for All the Rest

Sectoral bargaining under the RLA and wage boards is the exception to the rule. The present U.S. labor law system is based on decentralized, enterprise-based bargaining that offers few real advantages to workers but grants employers many opportunities to resist coming to the bargaining table. While industries governed by multi-employer contracts have created stable employment, established living wages, and resisted arbitrage, those that fall within the Wagner framework have witnessed a near-extinction of organized labor and left workers with only the minimal, standardized government safety net.

In the place of union-negotiated agreements stands a federal regulatory regime governing minimum wage, maximum hours, and overtime rules that was never intended to be a stand-alone system. Its supporters assumed that standards would provide a floor, on top of which unions in various sectors could negotiate better deals with employers and that tripartite wage boards would be needed only in a few low-wage sectors that were difficult to unionize. But the difficulties of enterprise bargaining have made federal and state minimum standards the norm by default, rather than a baseline. As FDR’s Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins declared, “I’d rather pass a law than organize a union.”

So why not simply achieve the goals of collective bargaining through direct legislation?

To begin with, relying on legislation and regulation alone to protect workers is bad for the economy. A single set of one-size-fits-all rules for wages, hours, and benefits cannot reflect the diversity of occupations and working conditions in different sectors of the economy. And trying to legislate different standards for different sectors in detail would require a level of bureaucratic micromanagement that might give even the most ardent progressives pause. In contrast, organized labor and organized employers can negotiate standards appropriate to their respective industries, revising them as needed without additional legislation or regulation.

Moreover, members of Congress, executive-branch policymakers, and federal judges of both parties inevitably reflect the biases of business lobbies and the college-educated professional class from which almost all politicians, civil servants, and political appointees are drawn. Given an opportunity for collective bargaining in one or another form, representatives of American workers may have a better chance of cutting a good deal through direct negotiation with their employers than they do of out-spending and out-lobbying trade associations or megadonors in the hope of influencing Congress or regulatory agencies.

Collective bargaining among labor and employers in some form can also minimize the need for an excessive welfare state. Today, most public policy experts left and right take for granted a future of weak unions and low wages in which the American workers’ incomes can only be sustained by greater levels of direct, after-tax redistribution from “winners” to “losers.” As their preferred vehicles of redistribution, left-neoliberals opt for more public services and social insurance, while right-neoliberals propose vouchers and centrist neoliberals tax credits.

But higher wages and employer benefits achieved through collective bargaining can reduce the need for massive redistribution by an expensive welfare state. Instead, centralized wage bargaining that guarantees living wages and perhaps employer-provided benefits can be supplemented by a relatively small “residual” or minimal welfare state for the retired or unemployable at limited cost to taxpayers.12Herman Schwartz, “Social Democracy Going Down or Down Under: Institutions, Internationalized Capital, and Indebted States,” Comparative Politics 30 (3) (April 1998). Indeed, a version of this, without the centralized collective bargaining, was the American model in the prosperous post-1945 era, with a limited welfare state supplementing employer-provided health insurance and pensions.

Most important of all, organized labor gives workers voice and agency in their own workplaces. If democracy is to be more than casting a vote for a few candidates every few years, it should include giving the majority of citizens a say of their own and a seat at the table in the occupations in which they spend most of their waking hours as adults.

To paraphrase Winston Churchill on democracy, collective bargaining is the worst system of labor relations except for all the rest. As for its prospects in the U.S., in familiar or novel forms, another quote from Churchill may be relevant: “The Americans can be counted on to do the right thing, when they have exhausted the alternatives.”

Recommended Reading

Conservatives Should Embrace Labor Unions

Brad Littlejohn interviews American Compass’s Oren Cass about why conservatives should be interested in the future of America’s labor movement.

Would Sectoral Bargaining Provide a Better Framework for American Labor Law?

Labor leader David Rolf and American Compass’s Oren Cass discuss the potential for sectoral bargaining in America.

Give Workers Power to Boost Productivity, Reduce Inequality

It’s an approach that echoes themes of the recent American Compass statement: a well-functioning system of organized labor should both “render[] much bureaucratic oversight superfluous” and reinforce the benefits of tight labor markets “through economic agency and self-reliance, rather than retreat to dependence on redistribution.”