RECOMMENDED READING

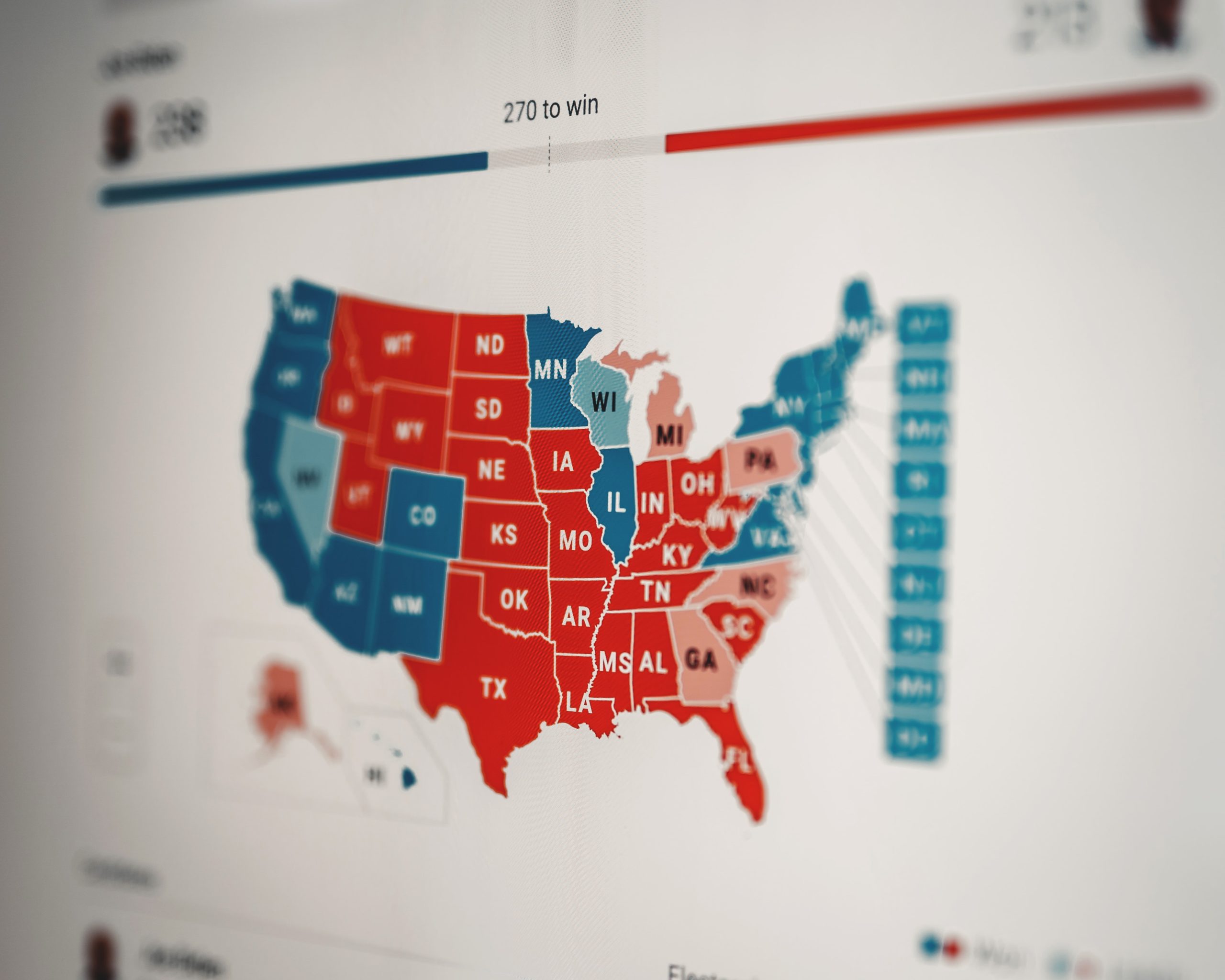

While Joe Biden will be the 46th President of the United States and Donald Trump will join the small club of incumbents who could not get re-elected, it’s fair to say that Biden’s triumph was not so overwhelming that it even begins to settle the question of which party will dominate the 2020s.

Biden will likely end up with a roughly 4 or 5 point popular victory, but his electoral vote advantage (306-232) simply replicates Trump’s advantage in 2016 and similarly includes several states taken by only the narrowest of margins. The GOP actually made gains in the House of Representatives and state legislatures. And the Senate likely remains out of reach for the Democrats.

These mixed results reflect both strengths and weaknesses in each party’s coalition. The Biden coalition continued to dominate the rising demographic constituencies at the heart of the party’s support base but underperformed with some of these voters relative to 2016. The Trump coalition retained strong support from its key white noncollege constituency but still saw significant defections of these voters to the other side, particularly in the suburbs, where there was also a surge toward Biden among white college voters. Neither party is in a secure position; both need to expand their support bases by winning back voters they have lost and retaining new voters whose aspirations may differ from their core constituencies. Here are the daunting challenges each party coalition faces.

The Democratic coalition

The Biden coalition may be summarized this way. Looking across available survey data, he carried nonwhite voters by a wide margin (though less than Clinton’s in 2016), ran up a modest advantage with white college voters and reduced Clinton’s 2016 disadvantage among white noncollege voters (particularly in suburban areas where most of these voters actually live). He carried young voters by a solid margin, as did Clinton in 2016, and made substantial improvements among senior voters, nearly breaking even with them.

This coalition bears some similarity to the popular understanding of what John Judis and I called, in our 2002 book, an emerging democratic majority. That argument has usually been reduced to the observation that demographic groups that lean Democratic are growing and those that lean Republican are declining and therefore the political landscape of the future is set: With time, the GOP will be overwhelmed, especially if Democrats can increase nonwhite and youth turnout.

But our argument in the book was actually that growing demographics simply provided an opportunity for political dominance—an opportunity that depended on maintaining a solid, though not majority, share of the white working-class vote and adopting a philosophy of “progressive centrism” that could weld a broad coalition together and prevent attrition among Democratic constituencies (e.g., Hispanics).

In that regard, the Biden coalition corresponds closely to the emerging Democratic majority coalition as properly understood, as it includes not just the growing constituencies but also an improved share of the country’s most important declining demographic, white noncollege voters, as well as more senior voters. And Biden’s purposive moderation is certainly in the vein of the progressive centrism we advocated in the book.

That said, the election results suggest some huge challenges for the Biden coalition going forward. Latinos are driving the growth of the nonwhite population in the country and, while still strongly Democratic as a whole in this election (63-35), that figure still represents a serious decline of Democratic support from 2016, particularly in Florida and Texas, but also in states like Arizona and Nevada.

Shoring up support among these voters is key to the future of the Biden coalition. The coalition also needs to retain the support it gained among both white college and noncollege voters and then make additional gains to insulate the coalition from populist backlash.

This will entail a Biden administration that cleaves closely to its implicit philosophy of progressive centrism and resists pressure to pursue unpopular causes. Above all, the administration must succeed in what it is surely its central task—containing the coronavirus and rebuilding the economy—by any means necessary. If that means priorities of the activist left must be deferred to accomplish this central task, Biden cannot hesitate to deliver the bad news.

As the early years of the Obama administration demonstrated, if voters do not see the main task as successfully accomplished, the potential for electoral backlash and coalitional fragmentation is vast. We can assume that skepticism about Biden’s ability to actually “build back better” is at least partially responsible for the decline in Latino support in 2020 and failure to gain even more support among white noncollege voters. Overcoming that skepticism can only come from effective governance which, in turn, could provide the basis for a dominant political role in the 2020’s.

The Republican coalition

The flip side of the Biden coalition’s vulnerabilities is the potential for a GOP revival. The Trump coalition at this point is manifestly not a majority coalition. But it does have a large core of support, built above all on strong support from white noncollege voters. The party will no doubt have a vigorous debate now about how to expand beyond that core in future years. The logical approach would be to seek additional support from white noncollege voters, but not to rely on that, given the unfavorable demographic trends. Latino working class voters would seem to provide a tempting target, given their burgeoning numbers and flagging support for Democrats.

Accomplishing this coalition-broadening will be not be easy for a Trumpified Republican party. While Trump’s confrontational and racially-tinged rhetoric has great appeal to his hardcore supporters, a broad GOP coalition would have to borrow the populist part of Trump’s appeal and join it to a focus on working class economic problems and a softer cultural approach to stop the bleeding among white college voters in the suburbs. Such an approach would risk, on the one hand, alienating some of the voters Trump has attracted through cultural extremism and, on the other, angering the party’s business and wealthy supporters whose interest in economic policy is generally confined to tax cuts and deregulation.

But Trump’s approach of combining cultural extremism with service to right-wing business interests has been a failure for a party aspiring to majoritarian dominance. It is likely time to try something new if the GOP is to take advantage of whatever missteps the Democrats may make.

Which coalition is in the better position for a future majority? At the moment, the Biden coalition corresponds closely to the emerging Democratic majority coalition as originally envisioned — it includes not just strong support among growing demographic constituencies but also an improved share of white noncollege voters as well as more senior voters. That could be a winning formula to build on for the rest of the 2020’s.

But as we know, demography is not destiny. The Trump coalition showed surprising strength in this election and chipped away at some constituencies the Democrats are counting on for future strength. More of the same could undermine the Democrats’ potential winning formula and possibly fuel a Republican resurgence as the decade unfolds.

Recommended Reading

A New Coalition, if You Can Keep It

As the pundits, campaigns, and lawyers continue to unpack this election, there are a few things we know for certain.

US Election: The Working Class is Up for Grabs

It’s now clear that Joe Biden will be America’s next president. While Democrats will undoubtedly celebrate this fact, the overall election results should give little comfort to them, given their failure to re-establish the party’s historically successful New Deal coalition, especially the working-class component.

On Buy American: Trump Should Listen to Steve Bannon, Not Steve Moore

A 2020 presidential contender unveiled a 700 billion dollar ‘Buy American’ plan today to rebuild America’s manufacturing sector devastated by the coronavirus.