RECOMMENDED READING

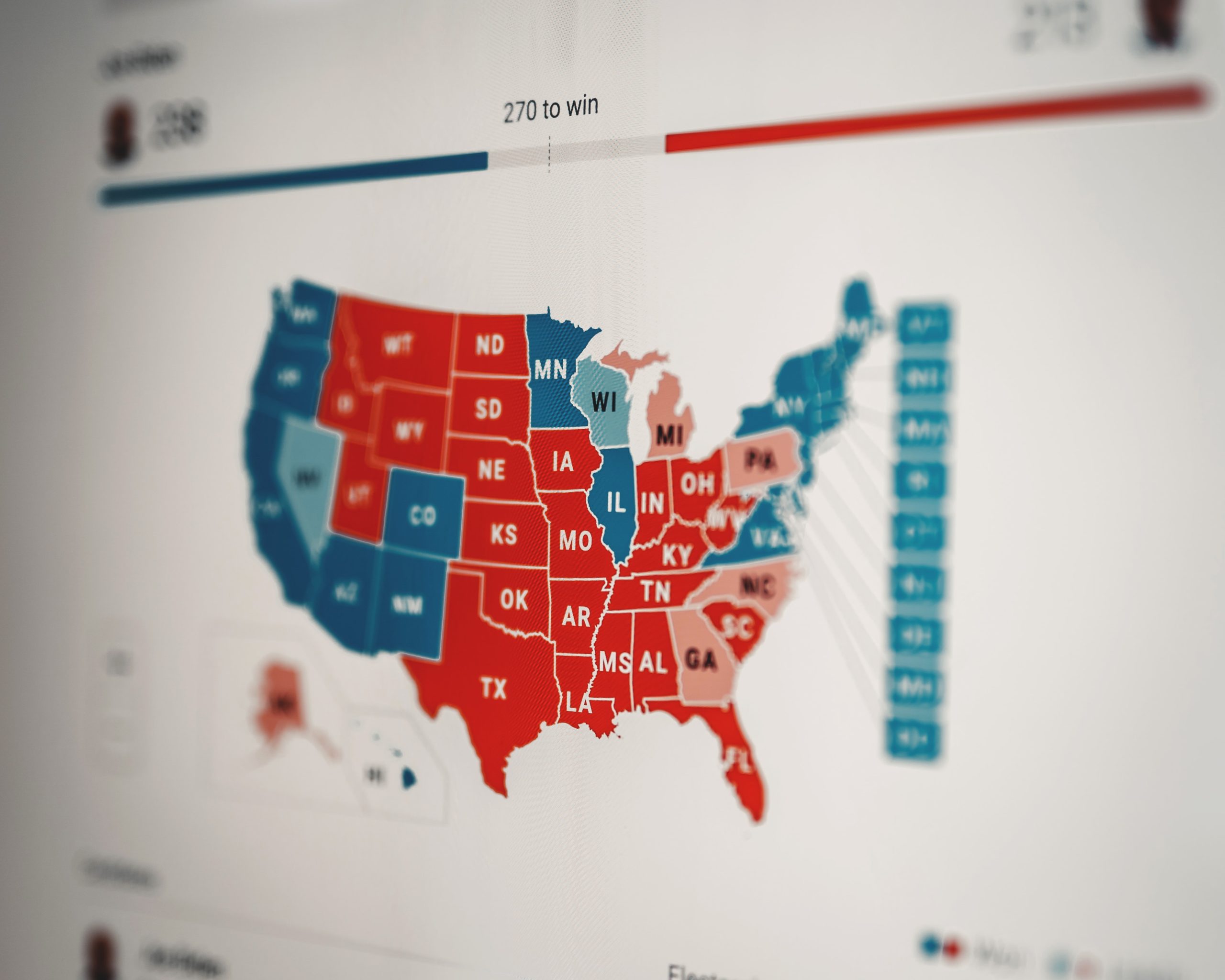

In the unlikely event Trump ekes out a victory in November, it will be because the electoral college let him win without the popular vote, and the democratic imprimatur it carries. Cognizant of this reality, Trump’s opponents have intensified their attacks on the electoral college itself—preemptively invalidating a second term and justifying, in the words of one leftwing group, “mass public unrest,” for which it and its affiliates have been preparing.

These attacks are obviously dangerous insofar as they heighten the risk of a contested election. But more to the point, they misunderstand what the Atlantic’s Shadi Hamid calls “the rules of the game.” The electoral college is itself the result of democratic processes, Hamid notes—and unless “it violates the constitution, what the democratic process produces … is legitimate,” whether or not it is Platonically fair. If Trump loses the popular vote, but wins the electoral college, he’ll have won, period; those who do not acknowledge his legitimacy will be courting just the sort of constitutional crisis they’ve accused him of engineering, with the uncertainties of mail-in ballots adding fuel to the fire.

Should the Reichstag burn down, this argument suggests, Trump won’t be its primary arsonist. Rather, the real threat to the Republic is anti-Trump backlash, of which popular vote fundamentalism is just one expression.

Like most contrarian arguments in the Trump era, this one captures some important truths. Trump is not the only threat to the Republic; his opponents have their own disdain for its distinctives, cultural and constitutional. Nor is Trump the only one with a partisan incentive to contest the election; as Hamid noted in a recent Atlantic essay, “Liberals have convinced themselves that Republicans are, in one way or another, cheating,” which means that even if Biden loses fair and square, he could face pressure not to concede. And after the summer streetfights in liberalism’s urban bastions, you’d be forgiven for fearing Antifa more than Trump’s ontologically dubious stormtroopers, who had not burned down any police stations last time I checked.

But in capturing these truths, the contrarian argument can obscure a more obvious one: Trump’s attacks on mail-in ballots have themselves delegitimized the rules of the game—and the example of the electoral college offers a simile for why.

Like the electoral college, mail-in voting is not standardized across state lines. Oregon has conducted all elections by mail since 1998 with the rubber stamp of the state legislature. In Pennsylvania, by contrast, an ad hoc mix of executive, legislative, and judicial actions have complicated the absentee system, leading to a major lawsuit.

Like the electoral college, mail-in voting currently seems to favor one party over the other, though under different conditions (those of the 2012 election, say) that could change. Also like the electoral college, mail-in voting is arguably unfair: Beyond creating ample opportunity for fraud and miscounts, absentee ballots get filled out before regular ones, which necessarily creates two classes of voters—those who have until election day to gather info and take last minute bombshells into account, and those who do not. (Requested absentee ballots, which in some states require an excuse, cut down on opportunities for fraud and enjoy official GOP support. Ballots mailed to all voters, whether they asked for them or not, are more the issue—though the rhetoric rarely reflects this distinction.)

And—like the electoral college—mail-in voting is democratically legitimate. The constitution lets states set up their own voting procedures, including absentee ballots, just as it lets them revise or abolish the electoral college if enough state representatives wish to do so. Since those procedures are themselves the result of a democratic process, they are democratically legitimate by definition. So even if mail-in voting generates bad outcomes, such as the administrative nightmares the Right is warning about, to reject the legitimacy of mail-in votes is in some sense to reject democracy itself. The rules of the game advantaged Republicans in 2016; if they advantage Democrats in 2020, that is no reason to ignore the rules.

Absentee ballots do differ from the electoral college in an important respect: While the unfairness of the latter is thought to inhere in the rules themselves, the unfairness of the former is thought to inhere in states’ inability to enforce the rules. “I’m not against mail-in ballots per se,” Trump implied (sort of) at last night’s debate. But fraudulent ballots break the rules almost tautologically. If we lack a reliable way of identifying such ballots, we also lack a reliable way of enforcing the rules—which means even if mail-in voting is democratically legitimate, many mail-in votes might not be. For better or worse, America is about to pick its next leader using a very error prone process. In that much, its current leader is correct.

But the constitution permits error-prone rules, and Trump swore an oath to uphold the constitution. Fulfilling that oath means doing everything in his power to minimize errors, not positing their existence before they’ve occurred. It means accepting the possibility of undetected error—present to some degree in all electoral regimes—and pledging to respect the results in spite of it. Anything less merits a simple, three-word response, familiar to any friend of the electoral college: them’s the rules.

Recommended Reading

Realignment Politics with Jerry Seib, Michael Brendan Dougherty, and Tim Chapman

What does the right-of-center’s economic debate mean for political leaders and how is it being translated into electoral politics in 2024 and beyond?

The Left of the Right

Matthew Continetti on the New Right and American Compass’s role in the realignment

The Future of the Biden and Trump Coalitions

While Joe Biden will be the 46th President of the United States and Donald Trump will join the small club of incumbents who could not get re-elected, it’s fair to say that Biden’s triumph was not so overwhelming that it even begins to settle the question of which party will dominate the 2020s.