RECOMMENDED READING

For liberal America, the projection that Joe Biden would win the presidential election prompted euphoric relief. After four years of shame for their nation, the president-elect would, in his own words, “restore the soul of America”. As if to accentuate their irrationality, raucous crowds gathered mid-pandemic and passed around champagne, carefully removing masks to place their mouths on shared bottles.

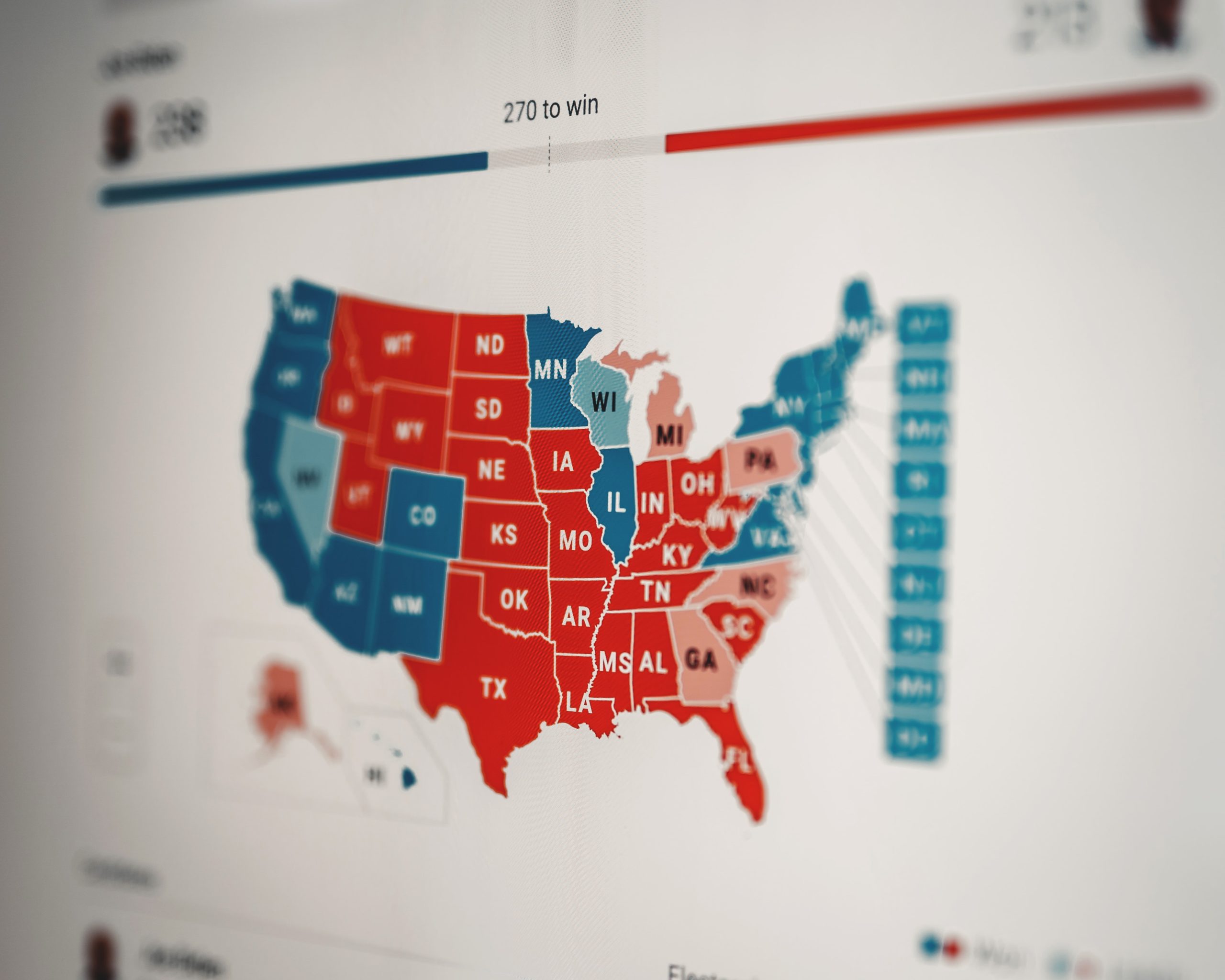

Election results determine who governs us. They do not tell us who we are. The US elected George W Bush in 2000 but could just as easily have elected Al Gore. After making Barack Obama a two-term president, a similar electorate chose Donald Trump, though with a few tweaks in a few states Hillary Clinton’s first term might have been concluding.

Understanding the US as an Obama or Trump or Biden nation allows everyone to feel proud when their side is in power and appalled when it is not. People imagine that those with whom they disagree are a solvable problem, just one blue or red “wave” away from disappearing for good. Victory becomes a “mandate” to impose an agenda on the roughly half of the country that does not support it, while a loss necessitates a “resistance” to fend off that same fate.

In reality, the US is an Obama-Romney-Clinton-Trump-Biden nation all at once. A substantial share of the country will disagree with any particular set of views. According to Michelle Obama, “tens of millions of people” voted this month “for the status quo, even when it meant supporting lies, hate, chaos, and division”, but most were also Americans in 2008 when her husband’s success in the Democratic primaries led her to declare that, “for the first time in my adult lifetime, I am really proud of my country”. Some fellow citizens whom she now condemns once rallied to the Obama message of “hope and change”.

Fortunately, America’s republican system of government does not see-saw power back and forth across the political divide depending on who has captured the most recent majority. Instead, it grants legitimacy to the political leaders who attain those majorities but then forces them to acknowledge fundamental disagreement and govern in a way that allows people of conflicting views to coexist peaceably.

“Whilst all authority in [the US] will be derived from and dependent on the society,” explained James Madison in Federalist No. 51, “the society itself will be broken into so many parts, interests, and classes of citizens, that the rights of individuals, or of the minority, will be in little danger from interested combinations of the majority.”

Arriving with plans by the binder-full, and able to accomplish few of them, winners invariably complain of “gridlock”. This misunderstands the nature of political progress. At the margin, gridlock appears endemic. But look backward, and widespread agreement springs forth. Both parties support entitlement programmes such as Social Security. Both agree roughly on what tax rates should be. Both support the basic structures of environmental laws, civil-rights protections and public schools. Each was hard-fought for. Comparable achievements will require enormous creativity, powerful persuasion and painstaking coalition building.

Will President Biden attempt actual progress? Ironically, his most enthusiastic supporters are likely to be the angriest if he tries. They won, so why talk of compromise? Republicans, too, would have to choose the hard work of governing over grandstanding in opposition. But perhaps there is reason for hope.

Alongside the unresolved polarising fare, new issues have been bubbling towards the surface. Members of both parties, for instance, now acknowledge that abandoning the nation’s industrial base was a mistake and a policy that could support the return of national supply chains is desirable. Recent legislation targeting the domestic semiconductor industry, co-sponsored by the Arkansas Republican Tom Cotton and Chuck Schumer, a New York Democrat, passed the Senate by a vote of 96-4. It has also passed in the House.

Likewise, both parties’ obsession with university for every student is changing to a recognition that many would be better served by other career pathways. Some conservatives acknowledge that the financial speculation of private equity and hedge funds is out of control. Some liberals acknowledge that a dying trade-union system needs reform. Where an issue has only recently emerged, such as the market power of tech goliaths, the sides may not find agreement, but then again maybe they will.

The art of governing is not in erasing division, but in helping a nation to live with it and thrive.

Recommended Reading

Don’t Kid Yourself About What Elections Reveal About America

American Compass’s Oren Cass argues that elections tell us simply who will govern us, not who we are, and it is critical to understand our fellow Americans who voted differently.

A Major Question Still Remains for Biden’s Campaign

American Compass’s Oren Cass reviews Joe Biden’s acceptance speech for the 2020 Democratic presidential nomination.

The Future of the Biden and Trump Coalitions

While Joe Biden will be the 46th President of the United States and Donald Trump will join the small club of incumbents who could not get re-elected, it’s fair to say that Biden’s triumph was not so overwhelming that it even begins to settle the question of which party will dominate the 2020s.