RECOMMENDED READING

In his recent post Matt Stoller observes that a common theme at The Commons thus far is “the reemergence of the state as the key locus of legitimacy for the exercise of power” and urges conservatives to think about corruption and statecraft. What’s needed, he says, “is a vision of how to structure such a state without succumbing to corruption.”

Corruption is, of course, a serious threat to our liberties, and Stoller’s piece is deeply thought-provoking. (Particularly striking is his treatment of the American Revolution as a response not only to a corrupt government but to the corrupt economic power of the East India Company; also, his framing of large corporations as “private governments in control of public infrastructure.”)

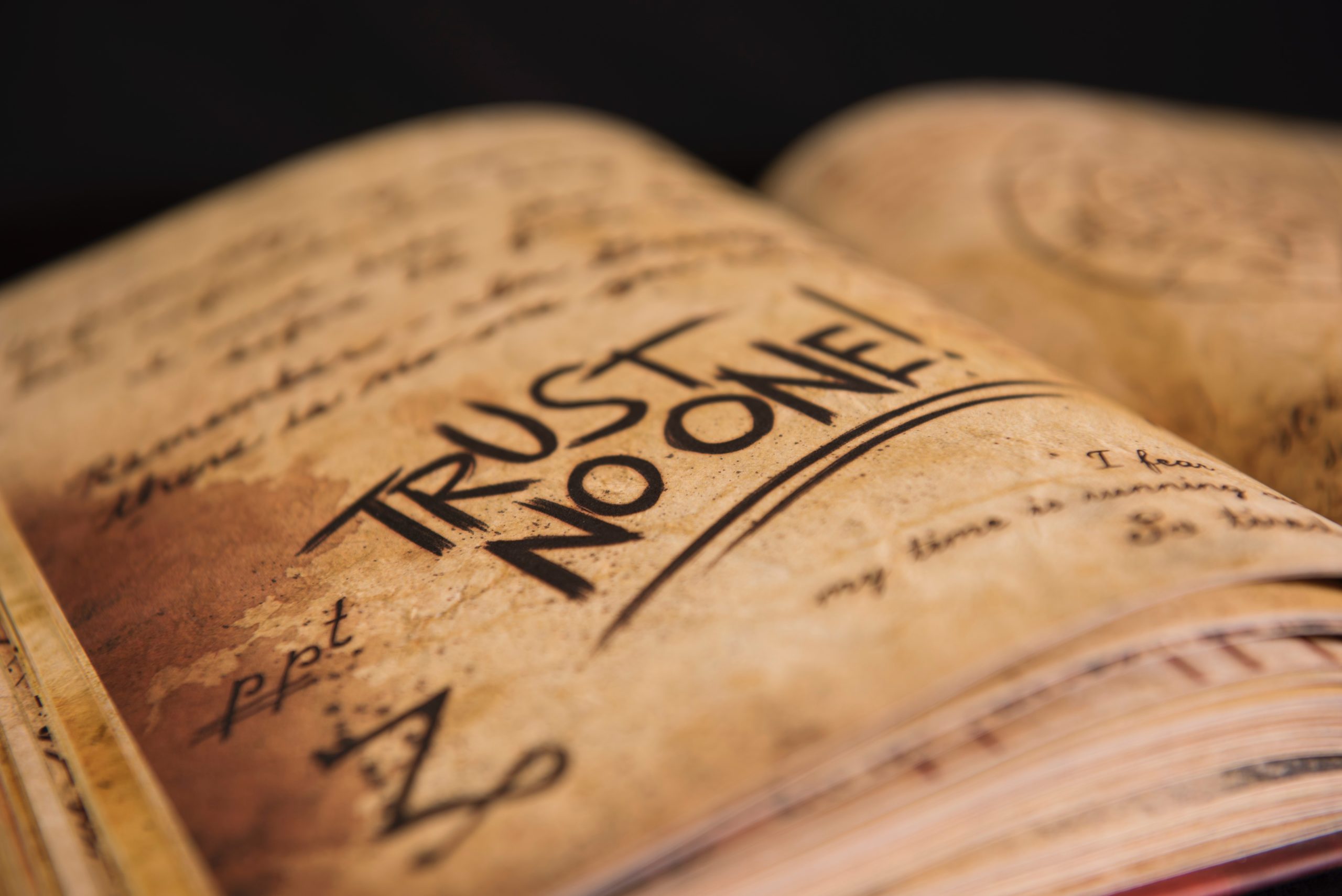

The post made me reflect on the spillover effects of corruption, the way that corruption in the government or market initiates trickle-down distrust. Though its origins may be specific (a particular instance of corruption), the effects are more akin to general anesthesia: an IV in one vein that spreads its effects to the whole body, corruption in one person or institution that leads to a more general social distrust of people and institutions of all kinds, the disorienting sense that nothing is as it seems and no one can be trusted.

This lack of solidity is a hallmark of our age, and something that I’ve heard many young adults, particularly those who are working-class, describe in the interviews my husband David and I began a decade ago. We’ve written before about Mike, a young man who told us that he wanted “to find a place where I can be at peace and have some structure and solidity to my life” but that trust issues had a way of interfering. As he explained, “everyone has to watch their ass all the time.” “No one,” he said, “is going to assume, ‘Hey, everyone has character.’ The first thing you’re going to assume is that person is probably wanted.” Or put more starkly by another young man, “I don’t trust nobody.” It was a refrain we heard unsolicited and verbatim from multiple interviewees.

Though our research focused on distrust within romantic relationships, I’m fascinated by the possible connections between intimate distrust and public distrust, the way that distrust seems a shape-shifting orientation to the world. I was not surprised, for example, to hear the man who was skeptical of Big Pharma and upset about its connections to the opioid epidemic talk also of the ways he’d been hurt and cheated on by women, and the woman who was sexually abused as a child tell me that she was convinced that the government was purposely spreading Zika and lacing heroin with fentanyl as a means of population control. (And we wonder why civic participation is so meager?)

Distrust conditions us to assume the worst, look for the worst, and find the worst. The effects of corruption, then, are damaging, multidimensional, and long-term—affecting even a person’s psyche and way of interacting with others.

Because of this it stands to reason that anti-corruption measures—like the antitrust scrutiny that Senator Josh Hawley calls for and Stoller mentions, or perhaps the 28th Amendment proposed by American Promise to get big money out of politics—could help to rebuild trust in government and the corporate world and thereby lessen the debilitating cynicism that leads to political apathy. It’s also possible that restoring trust in high places could have a positive effect on social trust elsewhere in civil society—maybe even affecting the way we are with our neighbors, friends, and family members. That would be a welcome development.

Recommended Reading

Whither Corruption and Conservatism?

Oren Cass invited me to contribute to this site not as a conservative but as a lefty and Democrat who is fascinated by the project of intellectual revival in which this network of thinkers is engaged.

Toward a New Anti-Corruption Statecraft

Matt poses some important questions below about how conservatives must defend anti-corruption statecraft against (tellingly) American libertarians and Chinese communists. I think it is right to suggest that the founders and their generation generally shared a robust sensibility that opposing, combating, and defeating corruption was properly political activity at the regime level.

Why the Free Trade Debate Needs the Real Adam Smith

Oren Cass is right to note that modern economists largely misunderstand Adam Smith. But the misunderstanding runs deeper and traces even further back than editorializing in 20th-century textbooks. For more than two centuries, scholars have ignored the relationship between Smith’s political philosophy and economic analysis.