RECOMMENDED READING

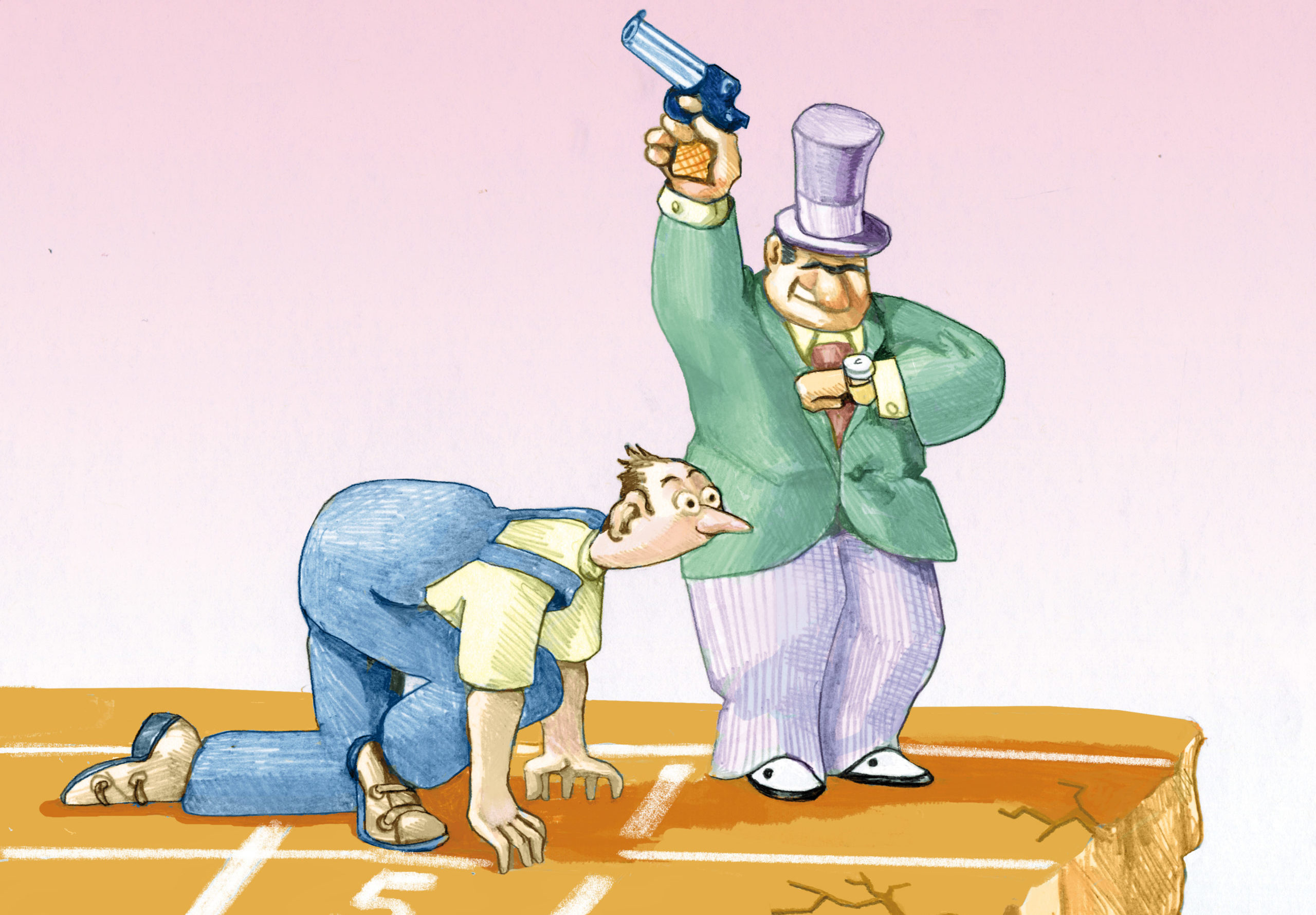

The “gig” may soon be up for Uber. A San Francisco judge’s ruling that ride-sharing services must treat their drivers as employees has both Uber and Lyft threatening to discontinue service in California, seemingly conceding that their money-losing business model relies not only on the subsidy of endless investor capital but also the legal arbitrage of ignoring the labor laws followed by others. But earlier this week, Uber CEO Dara Khorowshahi published a New York Times op-ed conceding the point that Uber treats drivers poorly and arguing for a different path forward.

Khorowshahi proposed a new employment status for gig workers that would maintain flexibility and independence while guaranteeing certain employee-like benefits and protections. In his plan, all gig companies would pay into portable “benefits funds” that workers could use for a range of benefits – from health and disability insurance to paid time off. In addition to the op-ed, Uber published a call to action for lawmakers and the industry to pursue further.

It’s a good first step. We ought to commend Uber for seeking accountability by placing constraints upon itself as well as seeking constraints from the outside – much as Oren Cass proposed in his essay last week.

But tellingly, Uber’s call for industry to “come together with government to raise the standard of work for all” includes no formal representation for workers or role for any form of organized labor. Instead, Uber has committed to helping its drivers register to vote in the upcoming election. Petitioning the government should not be the only pathway for addressing our economic challenges.

If gig employers like Uber wish to remain nontraditional employers, they should seek nontraditional ways for labor organizations to augment or even replace roles otherwise reserved for business or government.

The R Street Institute’s President Eli Lehrer and former SEIU President Andy Stern have proposed ways that states and industries might use waivers from federal labor law to experiment with new organizing models and enable existing labor unions to “unbundle” their services for members. Elsewhere, Lehrer has proposed new legal classifications for the gig economy – “flexible workers” and “job platforms” – that would guarantee basic employee protections, like anti-discrimination, and freedom from non-compete and “closed shop” restrictions for collective bargaining.

Such legal reforms could carve out the space for Uber and other gig employers to establish formal representation for their workers and a role for organized labor in:

- Benefits administration: Uber could devolve the management of its proposed portable benefits system to organized labor. There are already several models for union-administered portable benefits in other industries and countries. Uber could seek to create room in the industry for worker organizations to replicate Taft-Hartley Multiemployer Plans that exist in unionized industries or the Ghent system prevalent in some European countries, in which trade unions administer unemployment insurance.

- Codetermination: Uber has committed to giving workers “a stronger voice in our democracy,” but seems open to only one mechanism of worker voice: the ballot box. While essential, worker participation in the democratic system is unremarkable. Creating avenues for worker voice in the workplace, Uber might consider incorporating models of “codetermination,” such as letting workers vote for representatives on the company’s board or creating a works council system so that management may consult with drivers’ representatives.

- Sectoral bargaining: Uber and the gig industry might also experiment with ways to incorporate workers in negotiation over their basic terms of employment, moving the debate over labor standards from the public square and the state legislature to negotiations between the affected parties. Sectoral bargaining has the potential to expand worker power in the gig economy more tolerably than conventional bargaining. By broadening the scope of negotiation to encompass multiple firms, entire regions, or even the entire gig economy, sectoral bargaining could provide a less adversarial and more efficient framework for Uber and other gig companies to secure the input and buy-in of their workers.

Khorowshahi’s op-ed in The New York Times was an important step toward corporate responsibility in the gig economy, and Uber’s call to action and proposed constraints are promising models for corporate accountability. But gig companies must also recognize that outside constraints need not—indeed, should not—come from the state alone. Organized labor could offer a means of positive, countervailing power for workers in an industry where “flexibility” and “independence” have come at the expense of collective action and solidarity.

It is easy to offer workers promises for the future, but it takes a genuine commitment to corporate responsibility to give workers a proper stake in what those promises are and whether they are kept.

Recommended Reading

The Gig Economy is Paving the Road to Serfdom

The tech industry buzzword “gig” has distracted society from important questions about the gig economy that are surprisingly traditional: whether a business has employees or contractors, and how it can avoid payroll taxes and legal liability. Countless Silicon Valley business models have been built under the guise of gigs.

Freedom from Market Frictions

Digital platforms are but the latest innovation to empower workers and unburden consumers.

Remaking the Modern Market

Gig workers deserve fair labor markets that private platforms cannot provide.