RECOMMENDED READING

As I was reading sociologist Sarah Damaske’s new book, The Tolls of Uncertainty: How Privilege and the Guilt Gap Shape Unemployment in America, I was struck by a realization: though I’ve spent a good deal of the past 11 years interviewing working-class young adults in Ohio, I have met relatively few who have received unemployment insurance (UI).

Instead, I more often hear stories of people being denied or disqualified from UI, like fast-food manager Gina who says she was denied UI in 2020 when her employer said her leave was voluntary (her children’s daycare closed during the pandemic). Or Mark, a contract laborer for a construction company, whose work dried up but who was ineligible for UI because of his status as self-employed. Without health insurance, work, or any other benefits, an injured knee that required surgery left him with thousands of dollars of medical debt he was unsure if he’d ever be able to pay.

For those I’ve interviewed who do qualify for UI, the system’s clunkiness often renders it unhelpful. Dan filed for unemployment after losing his job as a union stagehand. “I filed for unemployment, and as soon as it went through I got work. So, I didn’t even get an unemployment check.” For such low-wage workers, for whom a week without work can be the difference between a place to live and an eviction notice, but who can find new work relatively quickly in the service sector, the existing UI system is nearly irrelevant.

The unprecedented strain of the COVID-19 lockdowns and economic recession have only reinforced these challenges. Far from the intentions of its Depression-era origins, the existing UI system is not working for America’s most vulnerable workers. A July 2020 report from the Congressional Budget Office found that, among the unemployed, the least educated were the least likely to receive unemployment benefits “because a relatively large fraction of people in that group will not qualify for such benefits.”

Given this state of affairs, The Tolls of Uncertainty is a timely inquiry into our unemployment system, how it fails many Americans and exacerbates class divides.

Drawing on interviews with 100 unemployed Pennsylvanians, Damaske concludes: “Unemployment is an institution—like workplaces, families, or schools—that both generates and reproduces inequalities.” Benefits are calculated based on income, giving the most to those who make the most (and coincidentally those who are also most likely to have substantial savings and to get severance pay—typically middle-class men). Meanwhile, low-wage workers, many of whom were below the poverty line even while working full-time, receive benefits that plunge them further into the kind of poverty and debt out from which it is difficult to climb.

But particularly striking are the ways in which the working and middle classes navigate the rules and regulations of unemployment differently—and how this exacerbates inequalities. We see this especially as people are looking for work, and in the outcomes of their searches.

Some job-seekers took a “deliberate” approach. Three-quarters of the middle-class women and nearly half of the middle-class men, Damaske found, sought work “quickly and methodically,” as if it were a job itself. These job-seekers felt they had the right to be somewhat selective about the jobs they applied to in the first place and to turn down a job offer that was not suitable. Damaske alleges that this is a “bending” of the rules since Pennsylvania law requires that benefit recipients must accept almost any offer of “suitable work,” defined as “any work you are capable of performing.”

Meanwhile, others opted to “take time”—half of the middle-class men in Damaske’s panel—and intentionally stalled their searches, often saying that they first needed a break. Pennsylvania regulations require UI recipients to actively search for work and to apply for at least two jobs a week, but there are simple ways to bend the rules—for instance, by applying only to positions for which you’re unqualified and unlikely to be hired. Typical of this approach was Neil, a hotel manager and avid fly-fisherman who lost his job during prime fishing season and decided to enjoy his hobby before beginning a job search. “I’ve been enjoying the past few weeks of not having much responsibility because it’s been 25 years of more than most normal people would work, and the stresses. So, I’m like gosh, darn, it’s my time.” A more extreme example was Dean, who used his severance pay to take a vacation to Europe and then returned home to collect unemployment.

The working class, however, could afford no such luxury, save for a few who considered a career change or a return to school. Two-thirds of working-class men and a quarter of working-class women took an “urgent” approach to their job search. Though they were the most likely to be chronically unemployed, working-class men were also the most likely to begin applying immediately to every available job, whether it was something they’d done before or not, within a 45-minute commute (the state requirement).

Tight finances and a strict interpretation of unemployment law often mean that the unemployed working class feels that they cannot turn down a “bad job.” For example, Anthony, a skilled electronics technician whose work in the past had earned enough for his wife to stay home full-time, worked for a year stocking shelves at a grocery store making $8/hour because he felt obligated to accept any job he could find. Work is approached as a means to an end—the end being family—unlike the more middle-class tendency to extract high levels of meaning from work outside the home.

According to Damaske, such divergent attitudes and approaches underscore research findings that, from a young age, the middle class learns that rules can be bent—even broken—whereas the working class learns a more literal adherence to authority. And in the case of the unemployment system, those who adhere strictly to the rules are at a disadvantage. One year later, most of the middle-class men in Damaske’s sample, including those who had taken time, were employed and either maintaining or almost maintaining the lifestyle they had before the job loss. Some even found better jobs than they’d had before. Almost everyone else was falling behind.

But it is working-class women, in particular, who found themselves “doubly disadvantaged” by the financial instability of unemployment and, in Damaske’s account, “those pesky traditional gender beliefs” associated with parenting. While they often needed to work, working-class mothers were “diverted” and lacked the basic resources—like child care or transportation—to begin and sustain a job search. Poor and working-class women, particularly single moms, echo these challenges in my own interviews. Earlier this year, some told me that a monthly child benefit could help unemployed parents get back to work by allowing them to fix a broken vehicle, have gas money, or pay a babysitter.

But the barriers to employment can be less tangible for these women. One interviewee told Damaske that the thing preventing her job search was “just stress.” Unemployed women, she found, often describe “feeling guilty” and then connect that sense of guilt to their decisions about health and housework:

It was striking to me that unemployed women attempted to make up for losing their jobs by doing more household chores, but the unemployed men did not. The women and men did not simply talk about guilt differently. Rather, guilt was a regular part of women’s language surrounding their unemployment as well as their household labor and childcare, but it was almost entirely absent from men’s talk.

The unemployed women in Damaske’s sample were more likely than men to give up their health insurance, to go without necessary medical care or doctor’s visits, and to stop eating healthy foods. Women often described these decisions as a way to make sacrifices so that their children and partners didn’t have to.

I have no doubt that the experience of this pervasive “guilt gap” is a disproportionately female burden. Though the context is different, in the past year since the birth of my fifth child I became aware that I was living in a state of near-constant guilt, thinking that, no matter what I was doing, I was not doing enough. I’m thankful to Damaske for highlighting the guilt gap and giving a name to realities many women experience but that are rarely acknowledged or poorly understood.

And yet, self-sacrifice comes with the territory of motherhood. Tolls of Uncertainty, which can descend into tedious tit-for-tat accounting of household chores, ultimately loses this larger vision: “We must continue to interrogate the ideals behind expectations of mothering—specifically those that suggest mothers should place their families at the center of their lives and do anything for them.” What if many, women included, find aspects of these beliefs not pernicious but grounding?

The least we can do for moms who are sacrificing sleep and autonomy is to honor them by ennobling their sacrifices with some sort of shared cultural script that acknowledges the work they are doing. Without that, mothers risk living in the no man’s land between warring narratives—one that lionizes women’s paid work outside the home but dismisses unpaid work within it, the other that treats paid work as a potentially irresponsible distraction from a woman’s real work of raising children.

With this in mind, family policy conversations become, somewhat unexpectedly, relevant to the conversation about unemployment as one part of the solution. Damaske arrives at a similar conclusion, arguing that one important solution to the inequalities of unemployment is an expanded child care credit. While parents do need more support as they seek to combine work and raising children, I think that a solution that only helps families with all adults in the workforce disregards the preferences of the working class—even if they reflect “those pesky traditional gender roles.”

In my own interviews, I’ve found that working-class young adults are quick to distance themselves from the rigid gender roles in the home that they sometimes ascribe to their parents’ generation. “I’m not the barefoot and pregnant kind of guy,” one man said when describing why it wouldn’t bother him if his wife made more money than him, emphasizing that he sees himself and his wife as “equal.” At the same time, these couples are more likely to say that their ideal arrangement when kids are young is for one parent to stay at home—sometimes referencing their own memories of long hours in daycare as kids. An at-home parent—whether it’s mom or dad—is often seen as an obvious good, if one can afford it.

A more universal child allowance or some alternate family support would honor this diversity of preferences and, rather than being a disincentive to work, could increase labor force participation. Such supports could be complemented by reforms to help the UI system better meet workers’ needs—like greater clarity about rules and eligibility in the handbook and orientation for newly unemployed, increased federal support of career and technical education (Damaske notes that, among the working class, those with specialized vocational training were more likely to rebound after employment), and new benefit calculations that match minimum wage workers’ incomes at 100% and tier replacement levels for everyone else.

But such an approach requires a different set of values, a renewed appreciation of the work of the home as more fundamental than the marketplace, and of the family as, in Erika Bachiochi’s words, “that person-oriented island in a market-driven sea.” In the economy, a person may be moved about in the chess game of corporate mergers, or replaced in the chase for short-term profits, but in the family no person is interchangeable. And though the market may deal its impersonal blows, we ought not to lose sight of the personhood of the unemployed, nor the families to whom they are bound.

The Tolls of Uncertainty: How Privilege and the Guilt Gap Shape Unemployment in America, by Sarah Damaske (Princeton University Press, 336 pp. $28)

Recommended Reading

Time to End the Race-to-the-Bottom on Unemployment Insurance

While the unemployment rate had fallen to 6.9 percent in October, the employment-population ratio was 3.7 percentage points lower than in February. 6.7 million workers were no longer looking for work and 3.6 million workers were unemployed for 27 weeks or more.

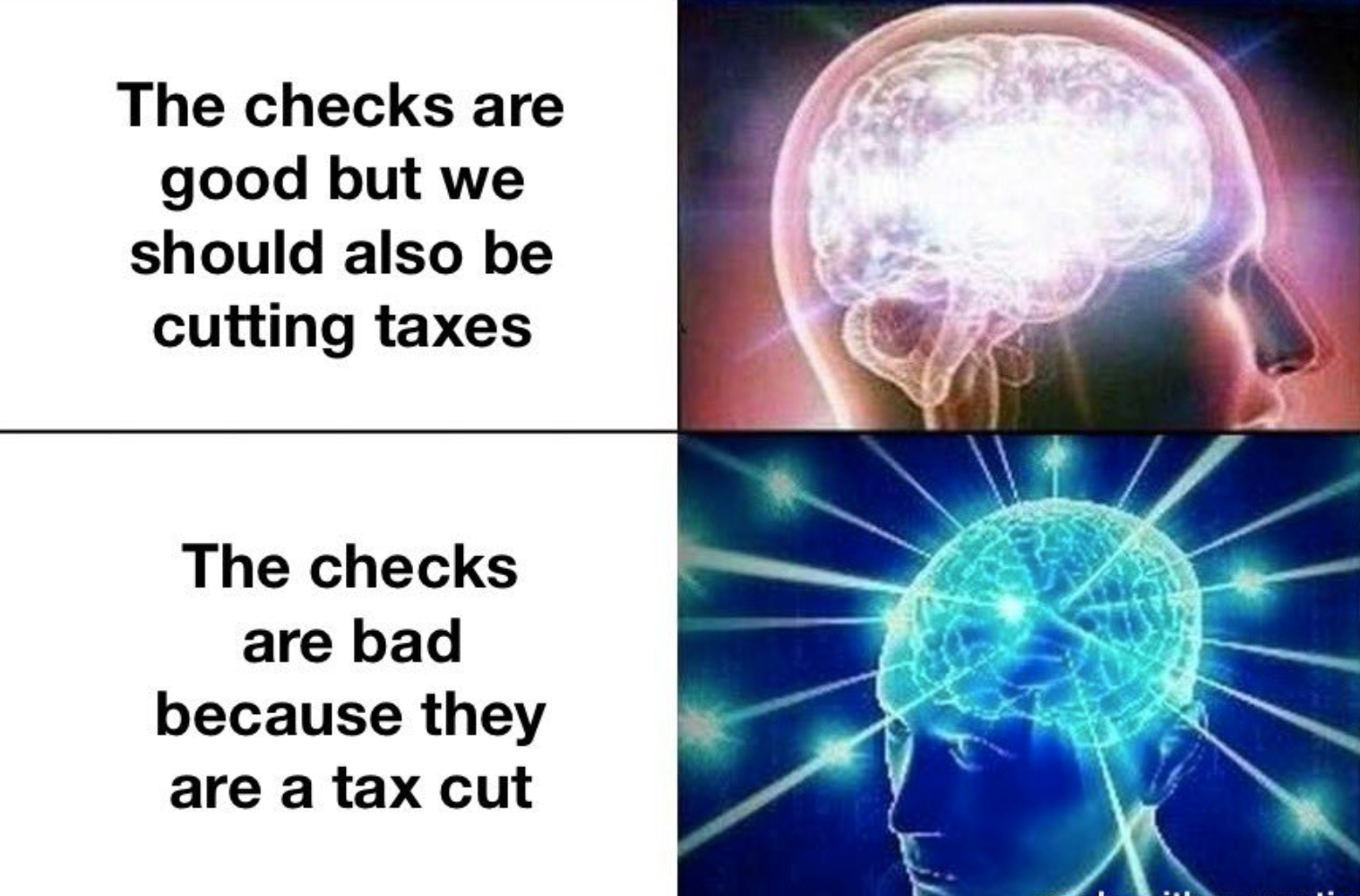

“It’s My %$!#ing Money” and the Hollow Populism of Stimulus Checks

“Checks” risks becoming the rallying cry for a hollow form of populism, one that seeks to merely extract value for the masses rather than build something new and permanent.

The Social Meaning of Family Benefits

No-strings-attached cash through a child allowance does not sever social ties or lead to the commodification of parenthood. It maintains expectations and parents will earmark for their child’s needs.