An overview of the hedge fund, private equity, and venture capital industries and the implications of their recent performance.

RECOMMENDED READING

Investing and deal-making occupy an outsized role in popular depictions of “business” like HBO’s Succession and Showtime’s Billions. They also occupy an outsized share of our elite: Over the last five years, the nation’s top business schools have sent nearly thirty percent of their graduating classes into finance.1American Compass analysis for “Magnificent Seven” business schools (Harvard, Stanford, Wharton, Booth, Kellog, Columbia, and MIT Sloan), employment reports (2015-19). But the buying and selling of companies, the mergers and divestments, the hedging and leveraging, are not themselves valuable activity. They invent, create, build, and provide nothing. Their claim to value is purely derivative—by improving the allocation of capital and configuration of assets, they are supposed to make everyone operating in the real economy more productive. The practitioners are rewarded richly for their effort.

Does this work, or are the efforts largely wasted? One might default to the assumption that an industry attracting so much talent and generating so much profit must be creating enormous value. But the elaborate financial engineering of the 2000s, which attempted an alchemy-like conversion of high-risk loans into rock-solid assets, and then placed highly leveraged bets against their performance, led to the collapse of some established Wall Street institutions, massive bailouts for others, and a global economic meltdown. Mergers and acquisitions, meanwhile, appear largely to be exercises in wheel-spinning: “M&A is a mug’s game,” explains Roger Martin in the Harvard Business Review, “in which typically 70%–90% of acquisitions are abysmal failures.”2Roger L. Martin, “M&A: The One Thing You Need to Get Right,” Harvard Business Review (June 2016). See also: “Why Do So Many Mergers Fail?” Knowledge @ Wharton (March 30, 2005); Scott A. Christofferson et al., “Where Mergers Go Wrong,” McKinsey Quarterly (May 1, 2004); and Richard Carr et al., “Merging the Miraculous: Mastering Merger Integration,” Business Strategy Review (Summer 2005).

Still, annual M&A deal value has risen by $1 trillion over the last decade,3Hugh MacArthur et al., Corporate M&A Report 2020, Bain & Company (February 24, 2020). and bankers continue to collect their “success fees,” which totaled $30 billion in 2019.4Eric Platt, “Wall Street M&A Fees Drop by More Than $500M in 2019,” Financial Times (January 17, 2020).

In the most lucrative yet opaque corner of high finance sit private equity and hedge funds. Their business model is to raise large pools of capital from “qualified investors”—high-net-worth individuals, pension funds, university and foundation endowments, and so on—and then pursue complex investment strategies that deliver returns superior to traditional, public equity and bond markets. For their trouble, they charge their investors a flat, annual management fee regardless of their performance—traditionally 2% of the amount invested—and also keep a share of any profits—traditionally 20%. Over a ten-year investment horizon, then, a typical $1-billion fund will consume $200 million in management fees alone, leaving just $800 million to be invested—and that’s assuming it achieves no profit. Globally, these funds contain more than $6 trillion.5Figures are global; Total hedge fund AUM is $3.194T as of Q4 2019 (BarclayHedge); Buyout fund total AUM is $2.067T as of H1 2019 (McKinsey); Venture capital total AUM is $988B as of H1 2019 (McKinsey).

“In other words, most fund managers are generating the results that one might expect from an elaborate game of chance—placing bets in the market with odds similar to a coin flip.”

Hedge funds pursue any number of investment strategies. Some attempt to generate positive returns regardless of how the market and broader economy perform, often taking long and short positions in a variety of publicly traded assets. Some take substantial stakes in companies and then seek to force different actions from management teams. Some take positions in more exotic assets, speculative insurance claims, sovereign debt of developing countries, or even lawsuits. Private equity funds acquire stakes in private companies, most commonly by borrowing heavily to purchase them outright (“buyout” funds), or else by making early-stage investments in start-ups (“venture capital” funds). Both are celebrated as uniquely potent: buyout funds are “creative destruction on steroids”6Kevin Hassett and Steven J. Davis, “Private Equity Is a Force for Good,” The Atlantic (January 16, 2012). and “a superior form of capitalism,”7“A Conversation with David Swensen,” Council on Foreign Relations (November 14, 2017). while venture capital is “where the ordinarily conservative, cynical domain of big money touches dreamy, long-shot enterprise.”8Nathan Heller, “Is Venture Capital Worth the Risk?” The New Yorker (January 20, 2020). The most successful fund managers earn billions of dollars and achieve semi-celebrity status.

The evidence does not support this enthusiasm. Hedge funds and venture capital funds appear to badly underperform simple public market indexes, while buyout funds have performed roughly at par over the past decade. Of course, some funds deliver outsized returns in a given timeframe; even a random distribution has a right tail. And there are managers whose strong and consistent track records suggest the creation of real value.9Eric Uhlfelder, “In Tough Times for Hedge Funds, These Are the Ones That Stand Out,” The Wall Street Journal (May 5, 2019); Amy Whyte, “These Private Equity Managers Are the Most Consistent Top Performers,” Institutional Investor (August 15, 2019). But generally, even the best performing funds in one period have shown little ability to replicate that success in the next.

In other words, most fund managers are generating the results that one might expect from an elaborate game of chance—placing bets in the market with odds similar to a coin flip. With enough people playing, some will always find themselves on winning streaks and claim the Midas touch, at least until the coin’s next flip. Except under these rules of “heads I win, tails you lose,” they collect their fees regardless.

Still, the picture is not straightforward. Disagreements persist over how returns should be calculated, which benchmarks are best for comparison, and which timeframes are most relevant. Should hedge funds be thought of as a form of volatility-combatting “fixed income” and compared in performance to bonds, or are they in fact much riskier? How to account for the fact that a stock can be sold at a moment’s notice, while money invested in a private equity fund might be inaccessible for a decade or longer? What about the inherent difficulty of estimating the value of private equity assets?

Even where agreement exists on what has happened, forecasts diverge. In 2018, Verdad’s Daniel Rasmussen observed in American Affairs that “since 2010, private equity has, on average, underperformed the public equity market.”10Daniel Rasmussen, “Private Equity: Overvalued and Overrated?” American Affairs (Spring 2018). Likewise, in its Global Private Equity Report 2020, Bain & Company noted that for the past decade “U.S. public equity returns have essentially matched returns from U.S. buyouts,” which (to put it mildly) “is not what PE investors are paying for.”11Bain & Company, Global Private Equity Report 2020. But while Rasmussen and Bain share a diagnosis—that rising asset prices have squeezed potential returns—they reach opposite conclusions. Rasmussen worries that deals in recent years, done at the highest valuations and not yet factored into reported results, “are likely to return close to zero percent per year.” Bain celebrated “another great year for PE” and predicted that “competition from the public markets will surely ease off.”

“A robust, competitive financial sector that allocates capital efficiently is vital to a well-functioning market economy. One that devolves into coin-flip capitalism has large costs and poses serious dangers.”

The unprecedented market volatility caused by the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020 may also reshuffle the deck. The S&P 500 fell by 34% from February 19 to March 23 and then erased 60% of those losses by mid-May. This should have been the moment for hedge funds to shine, though preliminary reports indicate many of the most prominent funds may still have underperformed12Mark Hulbert, “Hedge Funds Are Now Delivering as Promised, but the Winners are Tough to Find,” MarketWatch (April 29, 2020); Nishant Kumar and Bei Hu, “Hedge Fund Hotshots Suffer Humbling Losses in Coronavirus Chaos,” Bloomberg (April 16, 2020). and that funds managing to limit losses will come nowhere near compensating for the gains missed in recent years.13Eric Uhlfelder, “Hedge Fund Defensiveness Finally Pays Off,” The Wall Street Journal (April 5, 2020). For buyout funds that load portfolio companies with the high fixed costs of heavy debt, and venture capital funds betting on start-ups nowhere near profitability, a lengthy economy-wide shutdown could spell Armageddon.14William Louch and Laura Cooper, “Coronavirus Unravels Private Equity Playbook for Some Retailers,” The Wall Street Journal (May 10, 2020); “Pandemic Set to Disrupt a Boom Time for Venture Capital,” PitchBook (April 14, 2020).

These issues are far from academic. A robust, competitive financial sector that allocates capital efficiently is vital to a well-functioning market economy. One that devolves into coin-flip capitalism has large costs and poses serious dangers:

- Rewards out of proportion to value creation can misdirect talent away from vital economic sectors toward ones that merely extract rents;

- High fees and underperformance can erode the socially vital savings of pension funds and non-profit endowments;

- Long investment horizons and “lock-up” periods can prevent access to needed capital in the event of crisis;

- Pressure to make ever-riskier investments in pursuit of ever-evasive returns can embed excessive risk throughout the financial system;

- Overreliance on investment models that demand rapid scaling with minimal capital can narrow opportunities for entrepreneurship;

- Floods of capital intent on “disruption” can dismantle established industries while failing to build sustainable businesses in their stead; and

- Leveraged strategies not only increase risk, but also can force operating companies to prioritize short-term cash flow over investment and growth.

The problems of coin-flip capitalism and the potential remedies have received too little attention from an American political system divided between a left-of-center happy to attack finance without reference to its actual characteristics and a right-of-center equally happy to stipulate that whatever the market produces must surely be desirable. Instead, careful scrutiny is warranted. How much do these investments really cost to access, who pays the cost, and who earns the profit? On what basis do the prospective investors evaluate these funds and choose to participate? What is the source of value that the fund managers claim to capture and how do they create it? What risks do these investments create that are borne elsewhere in the economy?

The Returns Counter

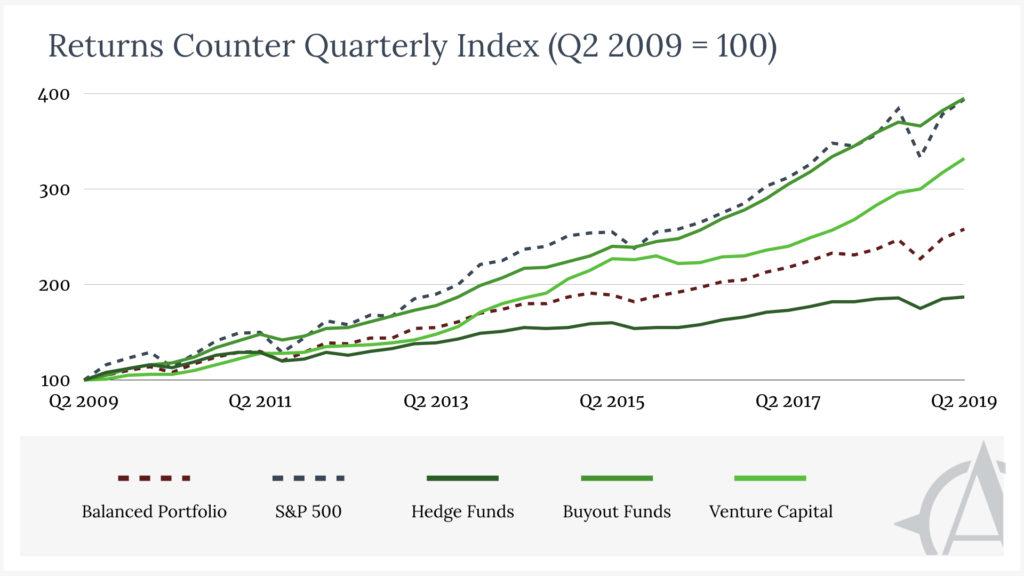

As a first step, American Compass has created the Returns Counter to track the performance of hedge funds, buyout funds, and venture capital. The Counter aggregates performance data and compares them to conventional public market benchmarks. The figures represent what an investor could expect to earn quarterly or annually from a comparably sized investment in each asset.

Data for buyout and venture capital funds are usually reported one year later—the latest data available in Q2 2020 are those from Q2 2019. All returns are net of fees and carried interest paid to fund managers.

Benchmarks

S&P 500 Total Return

The S&P 500 Index is a conventional benchmark for assessing the performance of the U.S. stock market. It includes the stock of 500 large companies traded at NASDAQ and the New York Stock Exchange and represents approximately 80% of available market capitalization.15For more information, see: S&P Indices The “Total Return” index accounts for both the appreciation of stock prices and the value of cash distributions, such as dividends, which it assumes are reinvested into the index. This most closely approximates the treatment of capital investment for long periods of time in alternative asset classes.

Over the past ten years, the S&P 500 Total Return index has returned 294%, or 15% compounding annually. In other words, $100 invested in mid-2009 would have been worth $394 in mid-2019.

Vanguard Balanced Index Fund

Some analysts argue that investments intended to “hedge” should not be expected to outperform the growth in risky equities during bull markets but rather to protect against losses. In this telling, investors regard hedge funds as akin to a balanced portfolio and their performance should be compared to a benchmark that includes lower-yielding but less volatile assets like bonds.16Donald A. Steinbrugge, “Index Comparisons Are Misleading,” The Hedge Fund Journal (April/May 2014). The Vanguard Balanced Index Fund (VBIAX), which offers a balanced portfolio allocated 60% to a broad U.S. stock market index and 40% to a broad U.S. bond market index, reflects performance of a balanced portfolio with broad exposure to the U.S. equity and bond markets.17For more information, see: Vanguard

Over the past ten years, the index has returned 158%, or 10% compounding annually. In other words, $100 invested in mid-2009 would have been worth $258 in mid-2019.

Any reader can move their savings into or out of investments like these at will, typically paying a management fee of roughly one-tenth-of-one-percent annually.

Hedge Funds

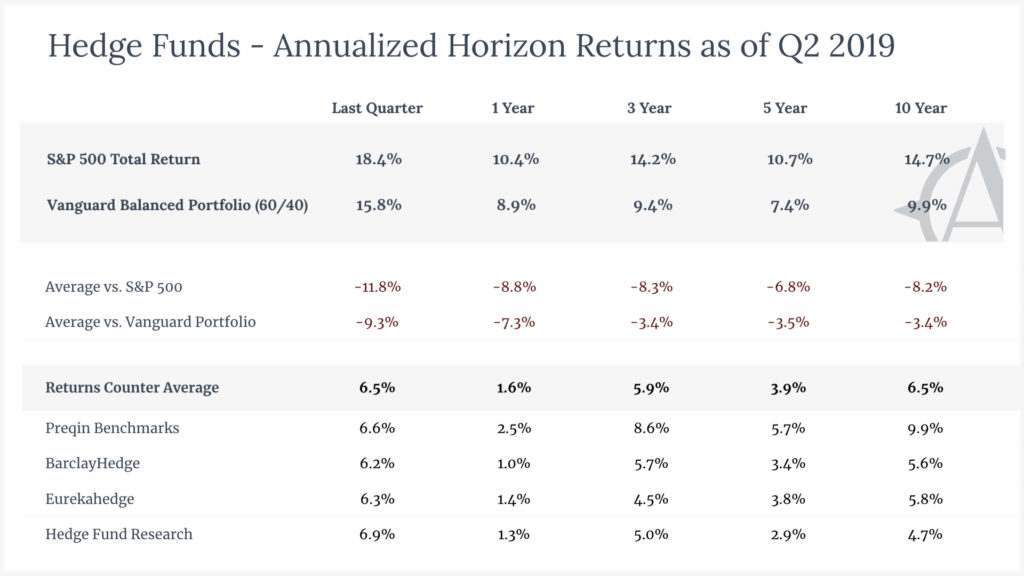

Hedge funds report their performance monthly, allowing the straightforward tracking of an index’s performance over time. Multiple research firms construct indexes that strive to capture the performance of hedge funds across the breadth of the industry and account for their relative sizes.

Returns

- 10 Years vs. Stocks – Over the past ten years, hedge funds have consistently underperformed the S&P 500 by a large margin—on average, by nearly 8 percentage points per year. An investment of $100 across hedge funds in mid-2009 would be worth $187 in mid-2019, less than half the value of an investment in the S&P.

- 10 Years vs. Balanced Portfolio – Over the past ten years, hedge funds have underperformed a balanced portfolio (60% stocks and 40% bonds)—on average, by nearly 3.5 percentage points per year. An investment of $100 across hedge funds in mid-2009 would earn $70 less, by mid-2019, than the same investment in Vanguard’s Balanced Index Fund.

- More Recently – Trends in hedge fund performance have been relatively consistent over the decade, trailing the S&P by anywhere from 7 to 9 points annually over one-, three-, and five-year horizons. Performance relative to the balanced portfolio has worsened with annual underperformance remaining steady at 3.4% annually over the three-, five-, and ten-year time horizons, and then falling further negative to 7.3% over the most recent year.

Volatility

While hedge funds do forsake the upside of equities to protect against risks of a market downturn, they also exhibit much greater volatility than domestic bonds and experience occasional meltdowns. For instance, Long-Term Capital Management, a hedge fund led by a successful bond arbitrageur and Nobel-laureate economists, lost nearly 95 percent of its capital in less than a year after generating annual returns upwards of 40 percent.18Stephanie Yang, “The Epic Story of How a ‘Genius’ Hedge Fund Almost Caused a Global Financial Meltdown,” Business Insider (July 19, 2014). Paulson & Co. collected an industry-record $5 billion in fees in 2010 after its bet against the U.S. housing market paid off. But the fund struggled thereafter and suffered consecutive double-digit losses throughout the 2010s.19Alexandra Stevenson and Matthew Goldstein, “John Paulson’s Fall from Hedge Fund Stardom,” The New York Times (May 1, 2017); “John Paulson Mulls Shutting Down His Hedge Fund,” Financial Times (January 22, 2019).

Hedge funds have always had a high failure rate. The average fund life-span fund is just five years, and one in three funds fail every year.20Dan McCrum , “Most Hedge Funds Fail,” Financial Times (July 31, 2014); Mitch Tuchman, “Warren Buffett: Why Hedge Funds Fail,” MarketWatch (October 27, 2015).

Bottom Line

Should hedge funds be evaluated against stocks or a balanced portfolio? The answer is probably that it depends. A balance of 60% stocks and 40% bonds might better approximate the kinds of risk/reward balance that the hedge fund manager attempts to improve upon, but strategies vary widely within the industry. Regardless, as noted above, hedge funds have underperformed. Indeed, one would have to set the hedge-fund benchmark at less than 20% stocks and more than 80% bonds to create a portfolio that the fund managers outperformed. Such a comparison is unreasonably conservative.

The market’s recent turmoil will provide a useful test. Hedge-fund managers might wish to claim so conservative a benchmark during a bull market, but that would hold them accountable for avoiding losses like the bond market did in early 2020—as the S&P 500 was falling 34%, the balanced portfolio fell by 23%. A 20/80 allocation would have fallen by less than 8%.

Private Equity – Buyout Funds

Private equity performance is published less frequently and with a significant delay (at most once per quarter, typically one year later) and their returns are traditionally evaluated with two different metrics. The “internal rate of return” (IRR) is the conventional metric used by private equity firms to calculate the returns delivered to investors over a period of time.21For more on IRR, see: Amy Gallo, “A Refresher on Internal Rate of Return,” Harvard Business Review (March 17, 2016); and Timothy Spangler, “Returns Drive Fees in Private Equity and Hedge Funds,” Forbes (July 30, 2014).

Because a fund will typically add and distribute capital throughout its life, investing in one is not quite equivalent to placing a dollar in the stock market and leaving it there. Analysts also use “public market equivalent” (PME) as an alternative performance metric designed to account for those cash flows, but their methodologies can vary widely and prevent aggregation.22For more on PME, see: “What Is the Difference Between IRR and PME?” PitchBook blog (March 23, 2020); and Rüdiger Stucke et al., “An ABC of PME,” Landmark Partners Private Equity Brief (March 2014). The Returns Counter uses IRR as its primary metric.

Returns

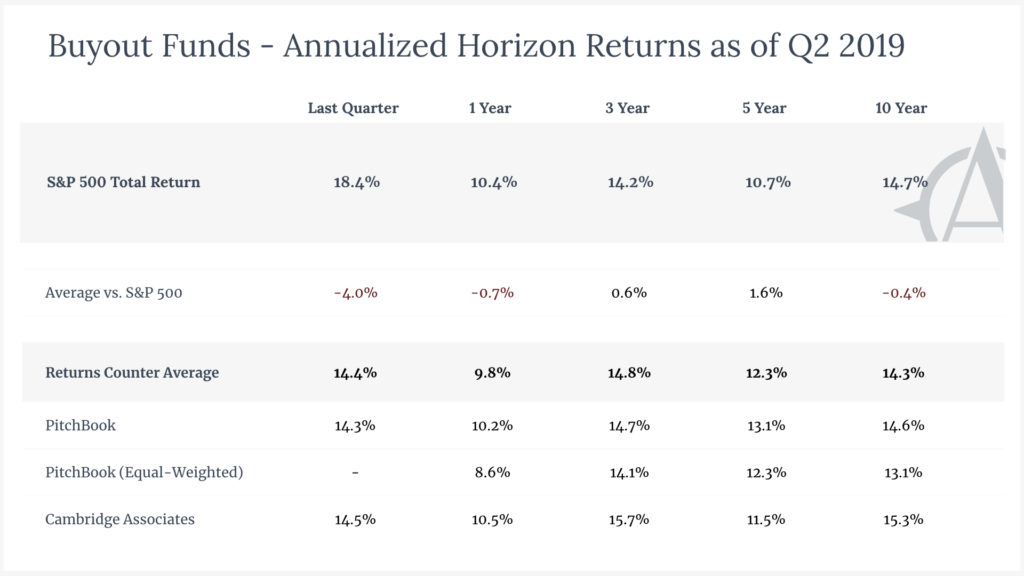

- 10 Years vs. Stocks (IRR) – Over the past ten years, buyout funds have delivered performance similar to the S&P 500. Aggregating the quarterly performance of buyout funds, an investment of $100 in mid-2009 would be worth $395 in mid-2019, 51 cents more than an investment in the S&P. The most recently reported ten-year “horizon” figures, meanwhile, show buyout funds generating an annual return 0.4 percentage points lower than the S&P.

- More Recently – Trends in buyout fund performance have fluctuated slightly over the last decade, beating the S&P by 0.5 to 1.5 percentage points annually over three- and five-year horizons but trailing it by 0.7 points over the one-year horizon.

Volatility

Since 2000, private equity firms with a bottom-performing buyout fund were just as likely as those with a top-performing fund to produce a subsequent top-performing fund.23Robert S. Harris et al., “Has Persistence Persisted in Private Equity? Evidence from Buyout and Venture Capital Funds,” Darden Business School Working Paper No. 2304808 (2014). Past performance, in other words, is not a reliable predictor of future success. Moreover, just as leverage can boost private equity returns, it can also exacerbate losses. A recent study of leveraged buyouts of public companies (i.e., private equity firms taking public companies private) found that one-fifth of the acquired companies went bankrupt—ten times the rate of similar companies that remained public.24Brian Ayash and Mahdi Rastad, “Leveraged Buyouts and Financial Distress,” SSRN (July 22, 2019).

Caveats

Measuring buyout-fund performance is complex, particularly given the unique risks associated with such assets:

- Cash flows – Investors in private equity must deal with unpredictable cash flows. After committing capital to a buyout fund, investors have little-to-no control over the timing or rate at which that capital is invested in target companies or returns are distributed. Instead, investors must find other uses for their capital when the fund is not using it, but this can also mean better returns during the period when the capital is actually invested.

- Illiquidity – Unlike public equities, investments in private equity are illiquid. An investor cannot simply sell assets or divest at will. Investment horizons can extend beyond ten years.

- Leverage – Private-equity firms finance their deals with high debt-to-equity ratios, and in recent years buyout deals have not only increased in value, but also become considerably more leveraged. Leverage ultimately constrains an operating company’s ability to invest strategically in long-term projects and increases the risk of the investment. But it also distorts buyout fund performance relative to the public markets. An investor who had been willing to accept similar risk by investing borrowed money in an S&P index fund would have easily outperformed the buyout investor.

- Valuation – Estimating the value of private equity assets is more art than science and the funds themselves have wide discretion, creating a so-called “mark-to-make-believe” problem for would-be buyout investors.25Matthew C. Klein, “Private Equity’s Mark-to-Make-Believe Problem,” Financial Times (April 16, 2016). Some research suggests that firms often employ financial reporting and accounting methodologies designed to understate volatility, overstate diversification, and boost returns.26Kyle Welch, “Private Equity’s ‘Diversification Illusion’: Economic Comovement and Fair Value Reporting,” (January 14, 2014). These methods create a “diversification illusion” to hide underlying volatilities.

These risks pose considerable trade-offs for which investors would typically demand a higher return as compared to the public markets. Some advisors and pension funds, for instance, discount private equity returns by 300 basis points when comparing them to public equities.27Eileen Appelbaum and Rosemary Batt, “Update: Are Lower Private Equity Returns the New Normal?” Center for Economic and Policy Research (February 2017). Bloomberg’s editorial board, reporting in 2018 on analysis by managers of the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority and Canadian Pension Plan Investment Board that sought to account for the risk of private-equity investments,28Jean-François L’Her, “A Bottom-Up Approach to the Risk-Adjusted Performance of the Buyout Fund Market,” Financial Analysts Journal 72 (4) (2016). concluded that “private-equity investments of recent vintage have actually lagged public markets” and had in fact done so every year from 2006 to 2014.29Editorial Board, “Where Have All the Public Companies Gone?” Bloomberg (April 9, 2018).

Bottom Line

In their early years, buyout funds generated enormous returns. Beginning around 2006, outperformance dwindled as more capital chased each deal, causing valuations to rise and funds to pursue larger targets. A consensus holds that returns over the past decade have been no better than in public equity and worsened over the period, even before considering the particular risks of private equity investments. Because of the subjectivity inherent in determining the value of recent investments, reported returns are a lagging indicator. Whether deals made in the late 2010s can reverse the trend, despite being made at record-high valuations, remains to be seen.

Private Equity: Venture Capital Funds

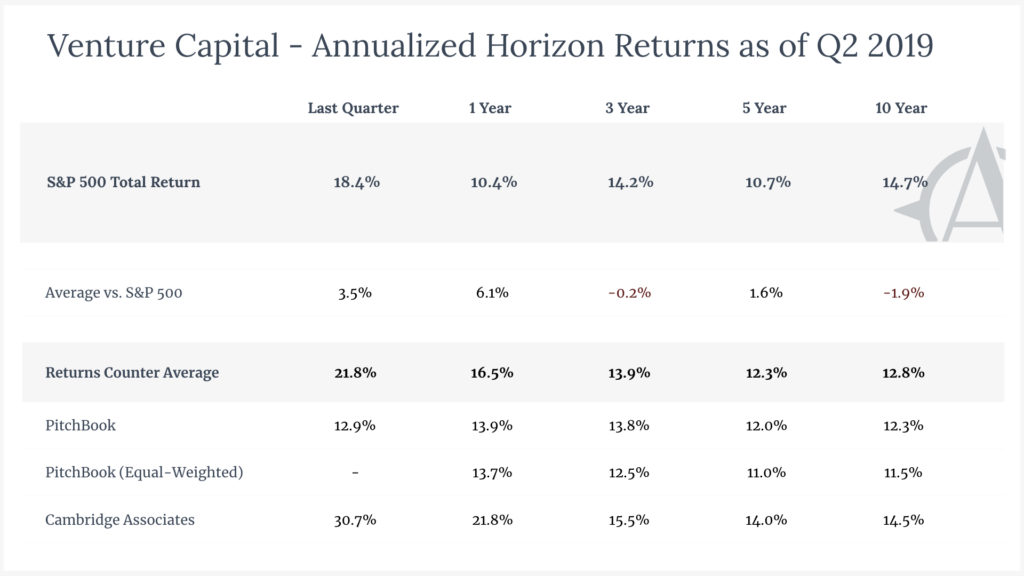

Venture capital is another form of private equity, which makes early-stage investments in start-ups. As noted above, private equity performance is reported less frequently and can be evaluated using two different metrics: “internal rate of return” (IRR) and “public market equivalent” (PME).

Returns

- 10 Years vs. Stocks (IRR) – Over the past ten years, venture capital funds have lagged the S&P 500 by 2.6 percentage points per year. An investment of $100 across venture capital funds in mid-2009 would be worth $332 in mid-2019, about $60 less than an investment in the S&P.

- More Recently – Trends in venture capital performance have fluctuated slightly over the last decade. Despite trailing the S&P by nearly 2 points annually over a ten-year horizon, venture capital has performed well during the one- and five-year horizons, beating the S&P by annual averages of 6.1 and 1.6 points respectively.

Volatility

Occasional vintages perform well, and particular funds generate impressive returns. But most funds fail, and only a tiny fraction generate the lottery-style returns that dominate headlines.30Diane Mulcahy et al., “’We Have Met the Enemy… and He Is Us’ Lessons from Twenty Years of the Kauffman Foundation’s Investments in Venture Capital Funds and The Triumph of Hope over Experience,” Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation (May 2012). It is estimated that only 5 percent of funds achieve the “venture rate of return” considered the baseline for success by investors. An estimated half of funds, meanwhile, are said to be losing money, while 35 percent are just breaking even.31Tomer Dean, “The Meeting That Showed Me the Truth about VCs,” TechCrunch (June 1, 2017).

Caveats

As a form of private equity, all the caveats listed above for buyout funds apply to venture-capital funds as well. But the focus on providing seed capital to start-ups also makes the industry unique. Such investing is particularly risky and investors should demand higher returns. In this respect, the industry’s performance is especially disappointing.

Venture capital also plays a vital role in a dynamic market economy, with the potential to create public value far beyond what its funds capture, but also to impose costs that its funds never bear. Whereas the typical buyout deal seeks to generate excess returns from an already-operating business, venture capital helps to create countless businesses—and even entire industries. Where and how venture capitalists choose to invest has an outsized influence on where and how the economy grows. If those choices deliver subpar returns, their consequences should be seen less as the inevitable result of a well-functioning market and more as a contingent outcome whose causes and effects invite the attention policymakers.

Bottom Line

Venture capital has been a perennial underperformer. As a whole, venture capital funds have struggled to meet standard performance benchmarks. In the last twenty-five years, there have been only two multi-year periods in which it outperformed public markets: the 1990s tech bubble and the 2007-09 global financial crisis.32“The Lure of Venture Capital,” Verdad (July 30, 2018).

Recommended Reading

Coin-Flip Capitalism

Coin-Flip Capitalism aims to help policymakers and the public better understand how the hedge fund, private equity, and venture capital industries function, what social and economic value they create or destroy, and how policy should respond.

Critics Corner with Steven Kaplan

Oren Cass is joined by private equity expert Steven Kaplan to discuss leveraged buyouts, bankruptcy, and the effects on workers.

Coin-Flip Capitalism: Q3 2020 Update

Commentary on developments in private finance and the Coin-Flip Capitalism debate as of Q3 2020