Few Americans realize how our system of organized labor is an outlier among Western nations. In some European countries, unions attract a greater share of workers and maintain less adversarial relationships with business. A better understanding of these alternative models can guide American policymakers as they address our labor policy challenges.

RECOMMENDED READING

The unionized share of America’s private-sector workforce has declined steadily for half a century and now stands at an all-time low of 6.2%. With this decline in “union density” has come the loss of benefits that once accrued to workers and their families.

Myriad explanations have been offered to explain labor’s fall. But the American structure of organized labor is itself much of the problem. Most of the decline in unionization is attributable to the decline of employment growth in unionized sectors and firms, a result not only of unions’ prevalence in stagnant or shrinking industries like manufacturing, but also the effect of unionization itself – raising labor costs for employers who then hire fewer workers and, with lower profitability, attract less investor capital. For instance, the labor market conflict endemic to the unionized manufacturing sector—namely work stoppages—contributed to the decline of employment in the Rust Belt. Overall, nonunion manufacturing employment was higher in 2019 than forty years earlier, while union manufacturing employment had fallen by more than 80%.

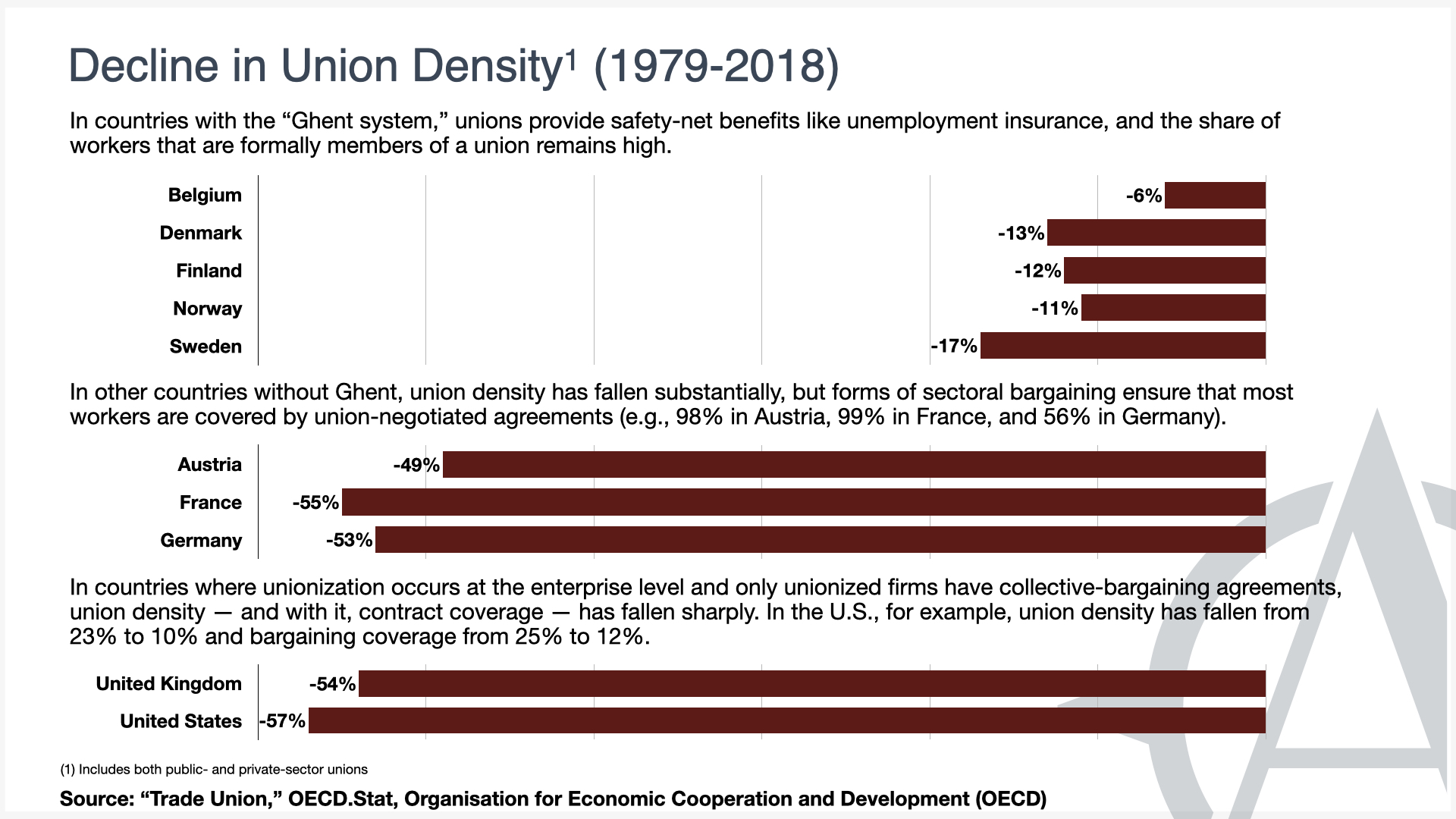

Other countries have witnessed declines in union density, too, but often to a lesser extent, suggesting that the decline of organized labor is not solely the consequence of economic development. The varied legal and social structures that shape and govern labor organizations play a significant role.

While debate in the U.S. has focused on how to get more workers to vote for a union, or give them ways to get out of one, a much richer variety of options is available. The last decade has seen a number of proposals from across the political spectrum to reform the legal structure governing labor unions: from universal worker representation and sectoral bargaining to federal waivers and new employee classifications. There has also been a great deal of experimentation outside of federal labor law with the rise of so-called “alt labor” as well as the revisitation of once-moribund state institutions, such as state wage boards, in an attempt to craft new functions for, and alternatives to, organized labor in the twenty-first-century economy. Developments like these could point the way toward a new labor law.

American workers support reform. Recent surveys show that workers want to have a wide array of organizations that give them a voice in the workplace, provide benefits and services to dues-paying members, and create avenues for advising and participating in employers’ decision-making. Their preferences underscore the potential for a renewed American labor movement, but they also highlight the limitations of the present American system of labor relations: the organizations hoped for do not exist, in large part, because legally they cannot.

American policymakers interested in pursuing genuine reform should begin by looking to countries in Europe where not only is union density stable and high, but also organized labor plays a constructive economic role. No other country’s model would be directly transferable to America, but familiarity with the alternatives and their tradeoffs can provide inspiration and a starting point for reforms to the American system.

The many variations possible for a system of organized labor exist along three dimensions, which correspond to the institutional roles that unions might play in democratic capitalism: as an association in civil society, an economic actor in the labor market, and a partner in workplace governance. This essay explores the varied forms and roles of organized labor in Europe and outlines possible considerations for U.S. policymakers seeking to reinvigorate the American labor movement in the twenty-first century.

Benefits & Services: Organized Labor in Civil Society

Well-functioning labor markets require the presence of benefits and services that help workers manage inevitable market frictions and that increase the value of workers to employers. Americans take for granted that government or employers should provide them. Our social safety net – including unemployment insurance and trade-adjustment assistance – is financed primarily by payroll-tax revenues and administered exclusively by the state. And our workforce development system consists of a hodgepodge of state-subsidized education programs and employer-provided training.

A more decentralized approach run through civil associations could be more flexible to local conditions and more responsive to workers’ changing needs. It could also create new incentives for participation in organizations that would otherwise struggle to attract members.

Labor unions are uniquely positioned and equipped to fill this role. Unions are themselves formed to facilitate mutual aid among workers and operate in concert with government and employers to advance workers’ interests in the workplace and wider labor market. In parts of Europe, labor organizations have adopted a leading role in providing services or administering benefits that state agencies or employers provide elsewhere. By carving out a space for labor in administering parts of the social safety net and leading workforce development efforts, these countries have managed to resist—or at least slow—declines in union density experienced in America. Labor organizations offer a value proposition to workers beyond the traditional benefits of representation and bargaining coverage and, in turn, attract and retain more members.

Unemployment Insurance

In European countries with the highest and most stable levels of unionization, unemployment insurance is voluntary and administered through unions in an arrangement known as the “Ghent system.” Ghent unions are prevalent throughout Northern Europe—namely Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, and Sweden. The generous benefits are offered to workers for modest fees and create effective incentives for workers to join and remain members of unions. Administering unemployment insurance is estimated to unionize an additional 20% of the workforce and rates of unionization where the Ghent model exists are among the highest in the world. The popular system relies heavily on state subsidization and employer contributions and operates a virtual monopoly in unemployment insurance. Even though workers have the choice to receive insurance either through a government agency or a union, most choose unions because they are more readily accessible and make it easier for workers to navigate the bureaucracy.

Roles for government and unions, and options for workers, vary by country. In Belgium, the birthplace of the Ghent union, the unemployment insurance system is mandatory, but unions are still heavily involved in its administration, running essentially a “de facto Ghent system” that has kept unionization fairly stable into the twenty-first century. In Scandinavian countries like Sweden, Finland, and Denmark, the Ghent system remains voluntary and attracts workers from across occupations and education levels. Beginning in the early 1990s, independent unemployment funds have been introduced in Nordic countries and have competed with the union-administered funds, offering the benefit without the requirement of union membership, and the member dues that come with it, which may explain some of the gradual erosion of union membership in those Scandinavian countries in recent years – particularly among new entrants into the labor market.

Worker Training

Labor unions improve and complement worker training programs in measurable ways. Union involvement in worker training has been shown to produce better outcomes in the workplace than training in which unions are not consulted or engaged. In the United Kingdom, union members receive more and better training than nonunion workers, while in Germany unions tend to increase training in existing apprenticeship programs. In the U.S. construction industry, joint-sponsored programs by unions and employers have higher program completion rates than those sponsored by employers alone.

Germany runs a robust vocational education and training system, including an apprenticeship program in which students seeking certification earn money and learn skills on the job. The national standards for such programs are established jointly by tripartite committees of experts from government, industry, and trade unions. In the course of collective bargaining (discussed below), trade unions also negotiate the salaries of apprentices. The administration of worker training is also handled by worker organizations. For instance, the examination bodies that oversee the creation and administration of tests for certification include worker representatives nominated by workers. Works councils (discussed below), which include worker representatives, oversee the local administration of vocational training programs at individual worksites.

Collective Bargaining: Organized Labor in the Labor Market

Collective bargaining is organized labor’s bread and butter, but in the United States its scope and effectiveness are quite limited. Workers are organized worksite by worksite into independent “bargaining units” that may then bargain collectively with their respective employers if a majority vote to unionize. While bargaining units may be voluntarily merged to expand the coverage of a collective agreement (if employers consent), they rarely extend beyond a single employer, much less to an entire region or industry.

This so-called “enterprise-based” bargaining framework creates a fragmented and decentralized pattern of unionization, in which fewer workers are covered by collective agreements and labor-management relations are aggressive and adversarial. The American legal framework for bargaining maximizes conflict and competitive pressures between not only labor and management, but also unionized and non-unionized firms. Employers resist unionization while labor pursues organizing tactics that force management to assent to elections and then squeeze as hard as possible in negotiations.

Lacking effective collective bargaining mechanisms, the terms and conditions of American employment are necessarily determined through a different system: federal regulation. Government agencies establish standards and protections for those things that collective bargaining could otherwise accomplish, from wages and hours, to health and safety, to termination processes. Thus, instead of privately negotiated arrangements brokered between firms and workers’ representatives, most American workers are covered by one-size-fits-all employment standards.

This regulatory regime is simpler than a patchwork of collectively bargained agreements governing different clusters of works. It guarantees that all firms are subject to the same rules, regardless of whether their workers are unionized. But it poorly accommodates sectoral and regional differences, let alone workers’ and employers’ priorities. And it leaves unions with relatively little to bargain over; contracts are negotiated atop regulations, not in lieu of them.

Given the obvious limitations of the American enterprise-based system, some reformers and labor leaders are considering the potential for collective bargaining at the sectoral, regional, and even national level – so-called “broad-based bargaining.” Labor market centralization is strongly correlated with higher union organization, and sectoral bargaining is the most conducive to union growth. The OECD reports that coverage by collective bargaining is only stable and high where some form of broad-based, multi-employer bargaining exists.

Broad-based bargaining improves the performance of unionized industries and firms along a number of different dimensions. It has been shown to reduce employee turnover and to establish better, and also more flexible, safety standards for particular industries. By including all employers within a given industry, it creates new incentives and collaborative forums for worker training; industries covered by sector-level agreements are more likely to invest in workforce development and devote greater resources to firm-sponsored training.

Broad-based bargaining’s benefits also spill over into the broader economy, improving both labor-market and social outcomes. It increases national employment by both reducing unemployment and increasing labor force participation, and also boosts productivity rates for covered industries. Meanwhile, it compresses wage distributions across entire industries, much as enterprise-based bargaining does within unionized firms, reducing economic inequality.

In countries with broad-based bargaining – particularly those were agreements are national in scope – unions are responsive to macroeconomic issues like wage-driven inflation and international competitiveness. They tend to strike a balance that accepts relatively lower wages but promotes healthier firms and rising productivity, which supports higher wage growth in the long run. In Germany, for instance, trade unions have agreed to set wages below marginal productivity in order to increase the competitiveness of export sectors.

Broad-based bargaining often employs what the OECD calls “organized decentralization.” While it emphasizes sectoral bargaining, it permits bargaining at multiple levels – from the national all the way down to the worksite – to ensure flexibility of broad-based agreements when applied to individual firms and locales.

In Denmark, Norway, and Sweden, for example, collective bargaining at the national or sectoral level establishes a framework that leaves room for local bargaining. Local negotiations may complement or deviate from the terms set in sectoral bargaining, enabling workers and employers to make trade-offs, choose à la carte, and establish lower standards if the parties agree. This “Scandinavian Model” balances centralization and decentralization in the collective bargaining process and maximizes flexibility for workers and management, incorporating bargaining at three different levels: at the national level between employer associations and national labor confederations, at the sectoral level between unions and employers, and at the local level between individual firms and their workers.

In Sweden, national bargaining establishes non-wage framework agreements. Wage bargaining then occurs principally by industry, with wages for more than three-quarters of workers set through a combination of sectoral and local agreements. Employer signatories to the collectively bargained contract are obliged to apply it to all employees, regardless of union membership. As such, over 90% of workers have their pay at least partly determined by local negotiation, but centrally bargained agreements also tend to include so-called “fallback agreements” which set wage terms for employees if no local deal is reached.

In Germany, sectoral bargaining sets standard terms from which local parties may negotiate for better terms and from which some firms may be exempted either generally or temporarily in response to an economic crisis. Collective bargain takes place at the regional-sectoral level between employer associations and confederations of labor unions. Collective bargaining agreements cover everything from wages to work hours to pay structures to the treatment of part-time workers to worker training. Germany also has a national minimum wage that is set by a commission of union and employer representatives in consultation with outside experts.

Several different agreements can apply to a particular German company, but if agreements are in conflict, the one signed by the larger union is binding. Agreements covering wages usually last one to two years, but agreements covering other issues can last up to five years or longer. Some agreements do not expire until a party opts to renegotiate the terms. Workers retain the right to strike, and unions may organize a strike to force employers to the negotiating table. Collective agreements include “peace clauses” that remove striking power so long as the agreement is in effect. This arrangement induces employers to renegotiate agreement preemptively and creates a smooth transition from one agreement to the next.

Representation & Codetermination: Organized Labor in the Workplace

In the typical American workplace, management has total authority and workers have little-to-no say in their employers’ decision-making. Unionized workers benefit from union representation that can handle grievances, file complaints, and petition management, but this leaves most American workers to fend for themselves. In theory, they individually negotiate their wages and benefits. In practice, they are presented a take-it-or-leave-it offer. As with enterprise-based collective bargaining, the relationship is inherently adversarial and there is little to actually bargain over.

American workers would prefer less adversarial, more cooperative relationships with their employers. A landmark study found that workers would prefer a form of representation that had a cooperative relationship with an employer but no power to make decisions over a form with power but that management opposed by nearly three to one. Recent surveys also show that workers place a premium on collaboration with management and input on corporate decision-making and prefer these alternative means of worker voice to traditional but confrontational ones such as strikes.

As companies in the United States flirt with “stakeholder capitalism” and American lawmakers weigh proposals for worker representation in corporate governance, reformers should consider Europe’s full range of models, where different workplace organizations and corporate governance structures ensure that workers have not only a voice within their companies, but a greater stake in their success.

Worksite Representation

One promising model of worksite representation is the “works council,” a legal organization independent of a labor union designed to promote cooperation between labor and management at the local level. Especially in the context of sectoral bargaining, University of Buffalo law professor Mathew Dimick explains, works councils fill a “‘representation gap’ left by the more universalizing, and therefore less particularizing, industry-level representation of workers’ interests by unions.”

Councils consist of elected employee and employer representatives who adapt conditions of the broader collective bargaining agreements to local circumstances and address workplace concerns not covered. In Germany, for instance, they are directly elected and vary in size based on the size of the firm – firms with 51-100 employees have a seven-member council and serve two main functions. First, they must be consulted on critical workplace issues such as safety or personnel decisions. Second, employers must inform and negotiate with them on a range of issues. For some issues like worktime, bonuses, payment methods, and surveillance, works councils have “positive codetermination rights,” meaning that they (or a tribunal plus a neutral chair) must agree to the decision.

Works councils are prevalent throughout the European Union. They predominate in Germany, where they are the only worker organization that operates at the enterprise level. German firms with as few as five employees typically have works councils, and among the largest firms (i.e., those with more than 500 employees) roughly 90% of employees are represented by one. Unlike the adversarial legal framework of American labor relations, the legal basis of the German works council is essentially collaborative: to work with management “in a spirit of mutual trust … for the good of the employees and the establishment.”

The power of a works council is defined by its sets of rights for dealing with management: information (must be informed), consultation (must be consulted), opposition/refusal (ability to block employer’s decision, subject to a labor court decision), and enforceable codetermination (employer cannot proceed without agreement or approval by a “conciliation committee”). In Germany, works councils’ rights are strongest in the domain of social issues (e.g., hours, vacation, payment methods, etc.). In dealing with day-to-day social issues, in particular, works councils can exercise rights of enforceable codetermination. But works councils’ rights are weakest in the domain of economic issues (e.g., financial performance, investment decisions, work processes, operational changes like closures or transfers, etc.). They are to be informed by management about the economic and financial situations of the firm and are to be consulted on work process and operational changes, but they do not otherwise have rights in addressing economic issues, which are considered to be the exclusive domain of the management.

On average, German works councils have twenty-three working agreements with management on social issues. Some collectively bargained agreements also include “opening clauses” that allow works councils and local management to negotiate over changes to the contract established at the sectoral level. Works councils may develop proposals just as the employer does, and the employer covers the full cost of the council.

Codetermination

To complement worksite representation either by works councils or local unions, some countries have adopted systems of worker representation on boards of directors that set the strategic direction of firms.

These models of “codetermination” offer a number of documented benefits. A recent study on “shared governance”—in this case, giving a third of boardroom seats to worker representatives—found that it increased capital formation and reduced outsourcing, with no measurable effect on wages, rent-sharing, profitability, or debt capacity. In Germany, in particular, a combination of works councils and board-level codetermination has shown positive effects on reducing short-termism in strategic decision-making and in reducing national income inequality.

In the German model of codetermination, there are two different boards. One, an executive board (also known as a management board), is composed of the CEO and other executives, while the other, a supervisory board, represents both workers and shareholders and is involved in the appointment of members of the executive/management board, monitoring business operations, and approving major strategic decisions made by the executive/management board. In corporations with 2,000 or more employees, workers elect half of the representatives on the supervisory board, while shareholders elect the other half and select the chair. In smaller corporations with 500 to 2,000 employees, workers may elect up to one-third of the supervisory board.

Studies of the German model suggest that workers’ first-hand knowledge of business operations adds considerable value to board decision-making when they can vote for representatives, translating into increased efficiency and market value. This is especially true of “industries that require more intense coordination, integration of activities, and information sharing such as trade, transportation, computers, pharmaceuticals, and other manufacturing.”

German codetermination, because it requires a balance of power between worker representatives and shareholders, also discourages “diffuse” ownership and encourages the “blockholding” of large portions of shares. In order to counterbalance workers’ representatives and maintain an aligned majority, there tend to be fewer shareholders maintaining greater equity stakes in companies, giving German public companies certain “semi-private” qualities.

A Broader Conversation about Organized Labor

A system of organized labor is an integrated structure whose parts depend on one another. The American structure is badly flawed and has produced dysfunction, no one is happy with it, and piecemeal reform isn’t going to fix it. Fortunately, there are many potential avenues for reform. Indeed, most structures of organized labor look nothing like America’s. Policymakers across the political spectrum need to be clear-eyed about the obvious limitations of America’s current legal framework but distinguish between the maladies of a law passed during the Great Depression and the promise of institutions that afford workers power and representation.

Looking across the Atlantic may supply promising models for such reforms. But the United States is not Europe. Our economies differ in their particulars, and (most important for labor relations) our cultures, norms, and systems of government can differ markedly. We cannot just import some other country’s structure, nor can we simply define some hypothetically ideal endpoint without establishing a roadmap from here to there and allowing for learning, adaptation, and institution-building along the way.

But appreciating the range of options provides questions for American policymakers to consider in the American context: What could unions do outside the bargaining context entirely? What broad-based bargaining might we want? What local representation and what interaction between the two? What codetermination? What role should remain for government regulation and where should bargained agreements be allowed to depart from it? The task is to answer these questions in ways that account for American institutions, norms, and values, advancing vital ends (e.g., greater collaboration, private ordering of labor markets and norms, greater solidarity) without destroying others (e.g., worker freedom and market flexibility). This conversation is one that conservatives should lead.

Recommended Reading

The Once and Future American Labor Law

American labor law has become worse than useless: a lower share of the private-sector labor force is organized today than before the National Labor Relations Act was passed in 1935. The time has come for an entirely new model.

Conservatives Should Embrace Labor Unions

Brad Littlejohn interviews American Compass’s Oren Cass about why conservatives should be interested in the future of America’s labor movement.

Give Workers Power to Boost Productivity, Reduce Inequality

It’s an approach that echoes themes of the recent American Compass statement: a well-functioning system of organized labor should both “render[] much bureaucratic oversight superfluous” and reinforce the benefits of tight labor markets “through economic agency and self-reliance, rather than retreat to dependence on redistribution.”