RECOMMENDED READING

Are we the passive victims of rapacious technology? Or fully knowledgeable about how technology works and in control of its role in our lives?

That’s a central tension of many of today’s tech policy debates, including the “Lost in the Super Market” essays: if data-driven services, sticky online content, and digital labor markets are surreptitiously exploiting consumers’ and workers’ interests—or if people are instead making sophisticated tradeoffs and using tech to take firmer control of their lives.

In other words: Are we humans working for technology—or is technology working for us?

The former argument reflects an overly dim view of consumers. When I agree to share my location with Waze, I’m aware that I’m giving something (my location) in order to get something (aggregated traffic data)—even if I don’t know how it all works under the hood.

At the same time, the latter vision of knowledgeable consumers with full agency requires the consumer to do a lot of work and check the fine print. While the techno-pessimistic view can be paternalistic, people are quite busy, and some unscrupulous companies have violated our trust.

There’s a middle ground here, and to extend Oren Cass’s analogy, the modern supermarket shows what it could look like: strengthening consumers’ power by helping them become smarter shoppers. For example:

- Just as supermarket coupons help shoppers get the best price on a product, the browser extension Honey easily finds online coupons, and services like Trim automatically negotiate savings in your monthly bills.

- Just as food nutrition labels help shoppers eat more responsibly, app permissions in iOS and Android tell you what types of data are being collected.

- Just as supermarket shelves label discounts and 2-for-1 deals, Uber and Lyft’s driver apps clearly illustrate drivers’ past and potential earnings and the best spots for passenger demand.

- Just as supermarkets offer store-branded goods at a cheaper price than premium brands, Amazon’s Basics branded goods help budget-conscious shoppers save money.

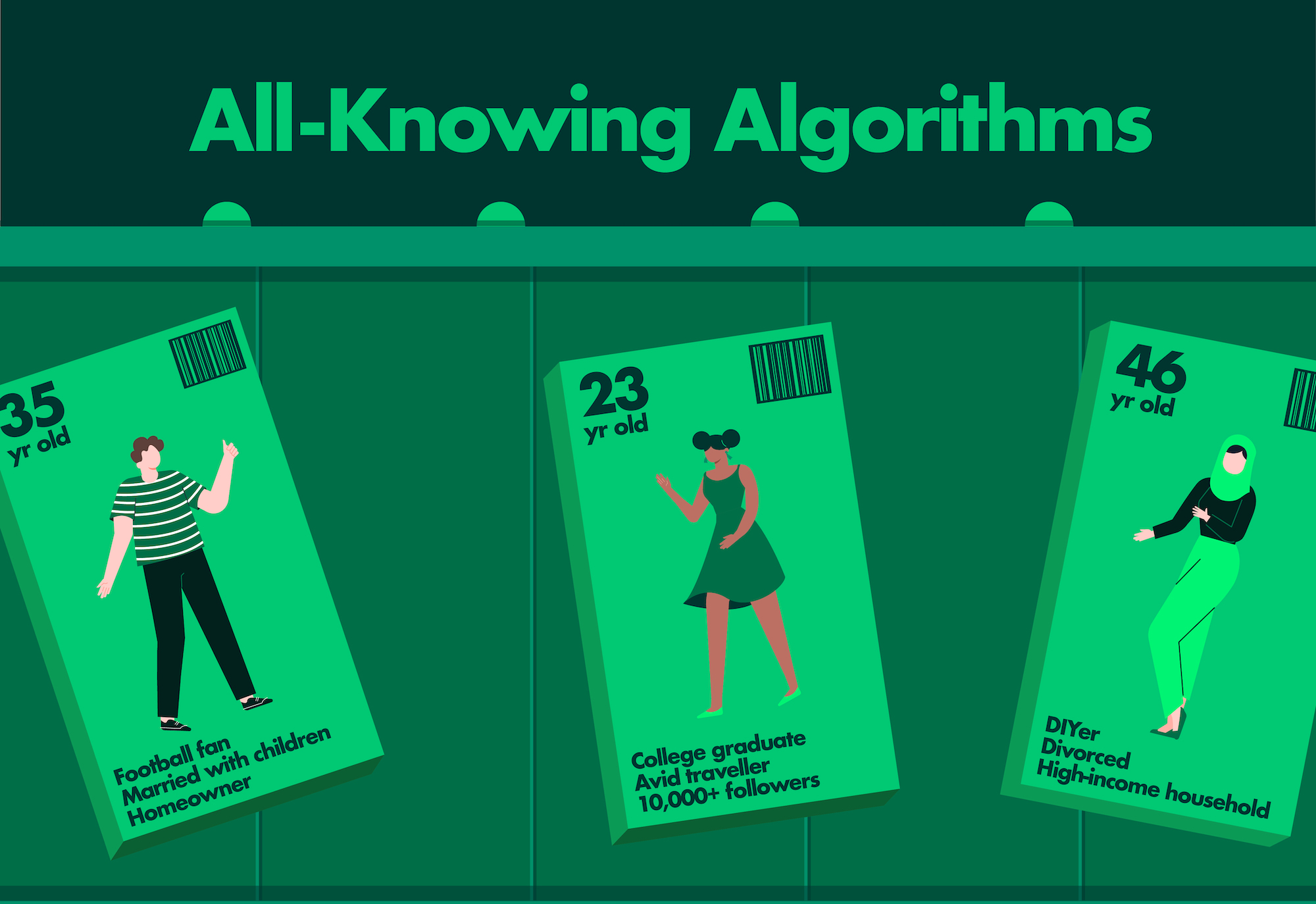

- Just as supermarket loyalty cards track your purchases in order to target discounts and promotions, Facebook and Google’s ad networks observe your interests in order to target a relevant ad—and let you pause or deactivate that targeting.

These companies’ tools give consumers more information and control. By contrast, regulation typically moves too slowly or ineffectually to solve people’s frustrations with technology. Europe’s much-mocked “cookie directive” requires Internet users to click an “accept” button so ubiquitous that it’s rendered meaningless.

Of course, neither in supermarkets nor in technology does merely providing greater choice and transparency ensure better outcomes. We have both record obesity rates and ample stories of tech abuses and excesses to prove that.

But ultimately, the best way to make tech work for people is smarter, more human-centric product design. Or to use a different comparison, tech should borrow from urban planning.

Urban planners define a social goal and then design a city to encourage that goal. Planners want in-person interaction, so they build town squares. Planners want healthy and local eating, so they create farmers’ markets. Planners want families to raise their kids nearby, so they build parks.

Tech services are starting to do the same. Twitter wants to discourage thoughtless retweets, so it’s using a “want to read the article first?” prompt when you try to share an article you haven’t read. Instagram wants to encourage warm feelings, so it tested removing “likes.” Parents want their kids to put down their iPads and go outside, so Apple built screen time controls.

This kind of thoughtful design also borrows from supermarkets: store layouts are designed to help busy shoppers quickly grab a rotisserie chicken or prepackaged dinner near the store entrance. Many small nudges can add up to meaningful behavioral change.

Urban planners have spent decades defining the kind of social behaviors they want to encourage in a city, but the tech industry is just starting that conversation. How do we design technology to encourage people to be more considerate, more responsible, more understanding, more information-literate? That’s next on the tech industry’s to-do list.

While that happens, it’s also partly on us to keep our technology human-centered. Several years ago, a friend told me that his teenage daughter became tired of attending parties where everyone was on their phone, so she organized a phone-free party. That kind of initiative and humanity can’t come from product design alone.

We aren’t victims of technology any more than a supermarket’s cardboard display of Oreos forces us to buy them. But industry should take seriously the challenge of giving people clearer information, better tools, and more control to make sure technology continues to work for them.

Recommended Reading

Five Principles of Tech Governance

The time has come to take stock of the Information Era and to govern it.

Selling the Digital Soul

The use and abuse of personal data pose a collective challenge that cannot be solved by individuals.

Big Tech, Antitrust and America’s Future

Wednesday’s “must watch” House Judiciary hearing with the CEOs of Amazon, Apple, Facebook, and Google raised a host of questions, including what the goal of antitrust should be (maximizing economic welfare or other goals, like protecting small business), and how should we think about platform industries.