The use and abuse of personal data pose a collective challenge that cannot be solved by individuals.

RECOMMENDED READING

To be online is to be watched at all times. Companies can track web-browsing behavior down to the most granular details—not only clicks and search queries but cursor movements and keystrokes. Smartphones send streams of precise location data without the owner’s awareness. The widespread adoption of “smart” devices that gather data—speakers, watches, even clothes—has only increased the range of activities monitored. Digital technologies so thoroughly mediate our lives that even the most commonplace personal activities like “pizza-and-movie night” generate loads of valuable personal information.

Nearly four-fifths of Americans are concerned about the amount of data that companies collect, and the frequency of major data breaches regularly renews attention to the security (or lack thereof) of sensitive personal information stored digitally. Privacy advocates have sought to enshrine a human right to digital privacy, even calling for a Bill of Data Rights and a new federal agency tasked with protecting user data. The United States has rules that govern the collection and distribution of sensitive personal information like financial and medical records. But what about the data collected on other digital activities—from messaging, to shopping, to browsing? Should the quotidian ever be considered confidential?

The initial challenge is that digital privacy defies straightforward regulation, or even definition. The norms, laws, and expectations that govern privacy in the real world translate poorly to digital contexts, where the distinction between “public” and “private” often escapes users. In theory, mass data collection and digital surveillance violate the individual’s “informational privacy,” his right to control information about himself. But in practice, one’s willingness to share personal information or be monitored depends on context and subjective judgments. A user is content to have GPS applications report his location if this helps to provide real-time directions and traffic updates, for example. But he often becomes irritated if those same applications report his location when not in use, or when other applications with no reasonable need for location data collect it nonetheless.

“Permitting surveillance is, in effect, the cover charge for much of the digital world, and thus for modern society.”

These challenges, as well as potential solutions, are typically framed as matters of consent. If users are aware of data-collection practices and can choose which to permit or prevent, they retain control over their personal information. Informed consent thus protects the individual’s subjective sense of privacy across contexts.

In practice, such consent is virtually impossible. Privacy policies, which establish the justifications for data collection, are either incomprehensible or inordinately long—often both. It would take the typical user an estimated 25 days each year to read the policy of every website he visited. The policies themselves are written by lawyers for lawyers, to protect companies rather than inform users. Opting out entails a cumbersome process that may not protect personal information, anyway, and requires users to avoid major platforms in favor of alternatives—no easy task. Permitting surveillance is, in effect, the cover charge for much of the digital world, and thus for modern society.

An Indecent Proposal

Suppose that such consent were plausible: that users could understand the terms of privacy policies, opt out of data collection at will, and turn to viable alternatives as needed. It might not make any difference.

Users claim to value their digital privacy more than they actually do. Eight in ten Americans believe that the risks of private data collection outweigh the rewards. Yet fewer than one in four users avoid certain Internet activities out of privacy concerns, and less than half update their basic privacy settings. Most gladly relinquish their data when presented with even the slightest incentives. Less than 2% of travelers, for instance, opted out of a Delta facial recognition program that saved less than two seconds at boarding. This so-called privacy paradox suggests that Americans understand their privacy to be tradeable, not inalienable. Their pragmatism may override their precaution as they evaluate trade-offs and negotiate terms of trade.

“We should not be so quick to dismiss our intuition that privacy has inherent value beyond the seemingly trivial dollar figures for which people seem happy to abandon it.”

Building a digital-privacy regime on informed consent is thus certain to further facilitate the commoditization of data. Users would sacrifice their privacy and relinquish their personal data at the right price—perhaps as little as 25 cents. Eric Posner and Glen Weyl have proposed such a “data markets” approach to governance, arguing that tech companies ought to compensate users for their data-generating activities as they would workers for their labor. If users create value for companies, they can claim some of that value for themselves. (Indeed, under the status quo, users are already effectively “compensated” in-kind via free access to a service, application, or platform.) Stipulating that consumers could understand their data options and manage their privacy preferences carefully, a straightforward, market-oriented quid pro quo may seem like a fair model for governing users’ informational privacy. It preserves individual choice and consent across contexts and returns a dividend to users in proportion to the value that companies might derive.

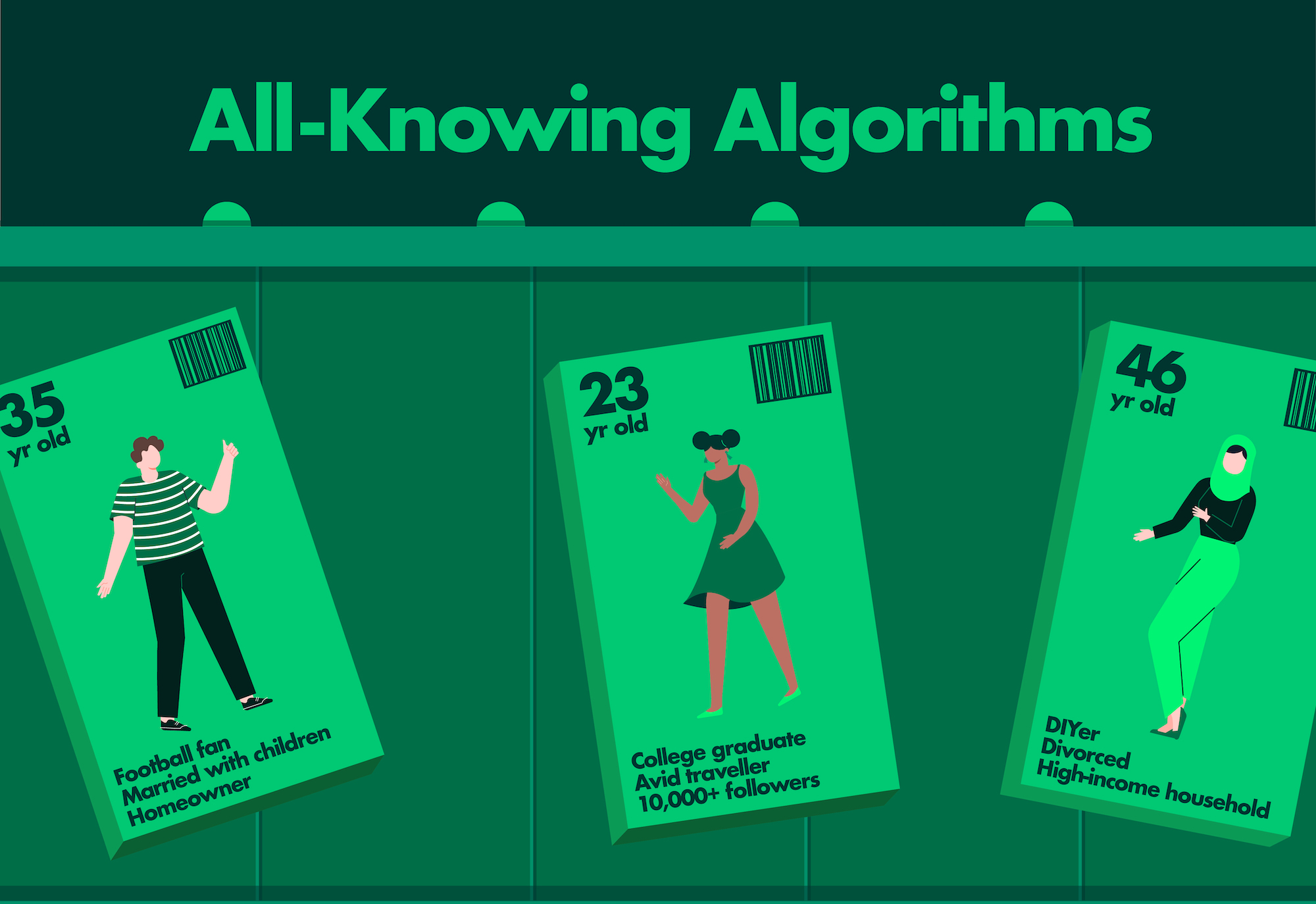

We should not be so quick to dismiss our intuition that privacy has inherent value beyond the seemingly trivial dollar figures for which people seem happy to abandon it. The data-industrial complex is a true wonder of the modern era. Information is bought and sold on a vast secondary marketplace, brokered by companies that most users have never heard of. Buyers aim to assemble data from numerous sources—mobile phones, social media, search engines, “smart” devices, even vacuums—to create as comprehensive a user portrait as possible: age, race, gender, minute-by-minute location, spending habits, financial stability, tastes and preferences, medical history, relationships, heart rate, and more.

To make use of these data, Silicon Valley firms have amassed expertise not only in data science and machine learning but also in animal science and neurobiology. Breakthroughs in artificial intelligence enable complex analyses of user behavior that predict individual decisions. Facebook, for example, classifies its users on more than 52,000 attributes and has developed a method to determine their emotional states. Its “prediction engine” processes trillions of data points to anticipate changes in consumption patterns.

“An individual’s personal data may sell for mere pennies on the market. But that trivial amount doesn’t reflect the degree of power that, once pieced together and studied rigorously, those data afford the companies that control the interfaces and infrastructure of digital life.”

These data and behavioral insights feed algorithms that affect lives in ways mundane and momentous. They determine the most relevant search results and binge-watching recommendations, as well as whether to renew a health insurance plan and whether to release someone on bail. Facebook can identify personal relationships where there is no immediately traceable digital connection on its own platform—a social worker and a new client, a sperm donor and his biological child, and opposing legal counsels. Companies track purchases linked to billboard advertisements that consumers have driven past and visits to a physical store linked to viewing a digital ad. Hedge funds buy consumers’ location data to analyze foot traffic in stores and anticipate market trends. The Weather Company, owned by IBM, can predict based on location data whether a user is likely to have an “overactive bladder” on a given day and thus be a target for drink advertisements.

An individual’s personal data may sell for mere pennies on the market. But that trivial amount doesn’t reflect the degree of power that, once pieced together and studied rigorously, those data afford the companies that control the interfaces and infrastructure of digital life. The threat to privacy in the digital age is not so much in being surveilled per se as in having more of one’s life shaped by behavioral nudges and advanced algorithms in increasingly unintelligible and unaccountable ways.

Preserving the Private Sphere

The sophistication of corporate surveillance has produced a yawning gap between what firms know about a user and what he knows they know, or even what he knows about himself—creating what psychologist Shoshana Zuboff calls “epistemic inequality.” The cumulative effect of data collection, aggregation, and analysis has been to transform the digital—and, increasingly, the analog—world into a massive behavioral-science laboratory. Users offering up their data are not akin to workers selling their labor but rather to test subjects selling themselves into digital experiments reviewed by no ethics board.

In some cases, such arrangements may simply exist outside the bounds of what a free society believes that its citizens can consent to—as is the case with indentured servitude. That determination may seem to have a paternalistic component, where policymakers assert that individuals lack the sophistication to make choices in their own interest. It may also seem to have a protective component, where power imbalances otherwise threaten to invite exploitation.

“Scrolling through a news feed of posts curated to provide the greatest possible dopamine surge can indeed be a pleasant experience. But a society in which this becomes the norm can nevertheless impoverish us all.”

But in the privacy context, the issue is perhaps best understood as one of national preservation. Surrendering to corporate surveillance may very well be in an individual’s best interests, at least as measured in terms of hedonic utility. Scrolling through a news feed of posts curated to provide the greatest possible dopamine surge can indeed be a pleasant experience. But a society in which this becomes the norm can nevertheless impoverish us all.

For example, a feedback loop in which people are presented only with those options that they are most likely to enjoy based on their previous choices becomes self-reinforcing, reducing the opportunity to try—and ultimately, the interest in trying—new things or consider new ideas. Curated media and social networks that show people the things that they are most likely to enjoy and the people most like themselves can fracture our common life and culture into hyper-segmented experiences. A world in which movie studios craft scripts based on predictive analysis of what elements will most please particular segments is a world of many formulaic Netflix originals and very little art.

Past choices have always shaped future choices, but perhaps never has this cause-and-effect dynamic been so thoroughly controlled yet so inexplicable. The algorithms that crunch users’ data and determine their digital environments defy not only understanding by typical users—but even by their creators. Such powerful and ubiquitous “black boxes” threaten to erode people’s sense of autonomy in, control over, and responsibility for their own lives. Why try to make decisions that are already being made for you? Why bother if you have no control? No one doubts that humans will gladly trade freedom for convenience. That doesn’t mean that they should.

This destruction of the private sphere implicates our public life. Hyper-segmented media can create epistemological bubbles and increase polarization. News feeds can be primed to provoke emotional responses that reverberate in socially destabilizing ways. Personalized algorithms may indulge private passions but jeopardize the public capacity to deliberate and organize.

“The American people must make a political choice about the level of personal privacy that they want to preserve.”

Many concerns from privacy advocates can seem melodramatic, and, to be sure, the effects are gradual and subjective. But against these concerns, the question must be asked: What is gained? Obviously, real-time location data are of great value in a navigation application. But does the weather application need to know your location at all times, lest you have to type in a city name? Does the pizza-delivery application? How much better is a world in which a product once added to a shopping cart on one site appears blaring in every ad on every other site for the following week?

The American people must make a political choice about the level of personal privacy that they want to preserve. They should ask policymakers to navigate between the extreme of some absolute human right to privacy and a purely consent-based framework. The former would be out of step with the pragmatic attitudes and revealed preferences of most people, while the latter would leave few checks on the exposure and abuse of unlimited personal information.

A new approach must acknowledge the limits of consent in data privacy and preserve a private sphere for all citizens. It should set appropriate limits not only on who may collect and access personal data but also on the appropriate purposes for which they may be used. What the digital age needs isn’t a new inalienable right to privacy but a digital environment that is intelligible and accountable, improving livelihoods as well as safeguarding our common life.

Recommended Reading

Policy Brief: An Online Age-Verification System

Congress should create a publicly provided online age verification system that would allow any person to privately and securely demonstrate their age online.

The Compass and the Territory

No particular worldview or ideology is necessary to see the reality of our political situation today. Due to the reshaping of our psychological and social environment by digital technology–a process laid bare by the unfolding coronavirus pandemic–our “map” of America is now out of date.

Reclaim Democracy From Technocracy

Our present predicament, characterized as it by an emboldened and rapacious post-U.S. Capitol siege Big Tech edifice all too eager to dutifully serve as a repressive ruling class appendage, was perfectly encapsulated on Friday by two of my Commons co-bloggers.