Demography may be destiny, but its party affiliation is not

RECOMMENDED READING

In 2002, we wrote a book, The Emerging Democratic Majority, which predicted that by the end of the first decade of the 21st century, the Democrats would have established a majority. It would not be the extended dominance they enjoyed from 1932 to 1980, but it would be a real advantage over several decades. We pointed to new groups within the Democratic coalition, including college-educated professionals and single women, and to the growing numbers of minority voters.

These voters were concentrated in postindustrial metro centers that we termed “ideopolises,” such as Boston, New York, San Francisco, and the Raleigh/Durham Research Triangle, where ideas rather than material goods are produced. Democrats would still need a significant share of working-class votes, and the votes of people who lived in small towns and midsize cities that had relied on manufacturing or mining, but not the solid majorities that had sustained the New Deal party.

Since 2010, American politics has been stuck in a teeter-totter between the parties. The majority we predicted did not emerge. What happened?

When the Democrats won the White House and Congress in 2008, our prediction appeared to have been confirmed. We were hailed as seers. Indeed, it seemed as if the new president, Barack Obama, in responding effectively to the financial crash and the Great Recession, might create a Roosevelt-like majority. But the Democrats’ dominance lasted only two years. Since 2010, American politics has been stuck in a teeter-totter between the parties. The majority we predicted did not emerge. What happened? Where did we and where did the Democrats go wrong?

Where We Went Wrong

We did get the new groups right. In The Emerging Democratic Majority, we argued that professionals, women, and minorities were displacing the old New Deal blue-collar working class as the key ingredients in a new Democratic majority. Professionals included nurses, teachers, software programmers, engineers, and scientists. Once typified by the dentist or doctor who ran his own business and was a loyal Republican, professionals began voting more Democratic in the late ’60s and by the 1988 election were supporting Democrat Michael Dukakis over Republican George H. W. Bush.

The second group was women, and particularly single and working women. Around half of adult women are now unmarried and their labor force participation in the 21st century has been pushing 60%, up from under 40% in 1960. Women had tilted Republican as late as 1976, but a substantial gender gap began to appear in 1980 and is now a regular feature of our elections. In 2020, women supported Biden over Trump by 13 points, while men supported Trump by six points.

The third group was minorities. Blacks had begun voting Democratic during the New Deal and, after the Republican repudiation in 1964 of the civil rights reforms, became uniformly Democratic. Democrats had historically been the party of immigrant groups and Republicans the party of Anglo-Saxon Protestants. Hispanics, except for Miami’s Cubans, had earlier been Democratic, and after the 1965 reform of immigration law, their numbers expanded rapidly. Most Asians had been voting Republican. In the 1990s, however, they started to come around.

We calculated that as working women, minorities, and the college educated grew in number, and as postindustrial metro centers grew, Democrats would have a durable advantage in both national and state-level elections—if they retained about 40% of the white working class and stayed close to an even split in heavily white working-class Rust Belt states. That did happen in 2008 when Obama won not only the vote of the new Democratic groups from the ’60s, but also white working-class voters in states like Michigan, Wisconsin, and Iowa.

Obama received 79% support among nonwhite voters, carrying Black voters by 88 points, Hispanic voters by 32 points, and Asian voters by 22 points. He carried women by 16 points, single women by 35 points, and voters under 30 by 30 points. He made a historic breakthrough with white college-educated voters, carrying them by a point and carrying white college-educated women by 9 points. And he won the postgraduate vote by 18 points, reflecting the Democrats’ growing strength among professionals.

Obama’s victory bore out our prediction that, based on the growth of postindustrial metropolitan areas, the Democrats would even begin to do well in southern states they had been losing since 1980.

Obama’s victory bore out our prediction that, based on the growth of postindustrial metropolitan areas, the Democrats would even begin to do well in southern states they had been losing since 1980. Obama won North Carolina by dominating the state’s thriving metro areas. In Mecklenburg County, the fast-growing heart of the Charlotte metro area, Obama bested McCain by 24 points, an amazing 44-point improvement over Michael Dukakis’s showing in 1988. He cleaned up in North Carolina’s Research Triangle, which includes Raleigh and Durham, and three major universities. He won Wake County, where the Raleigh metro area is located, by 14 points, a 29-point swing compared to 1988.

Obama also reversed the prior Democratic decline among white working-class voters, whom Kerry lost by 23 points in 2004. He cut the Democratic white working-class deficit to a comparatively modest 13 points nationally, and he carried the white working-class vote in states like Michigan and Wisconsin. Obama carried Michigan’s Macomb County, immortalized in a 1986 study by consultant Stanley Greenberg as home of the Reagan Democrats, by nine points.

In the 2010 election, though, Obama’s majority disintegrated. Midterm elections are normally bad for the incumbent party, but 2010 was especially bad for the Democrats. Republicans gained 63 seats and control of the House, performing especially well in the upper Midwest where Obama and the Democrats had seemed to make a breakthrough. House delegations in Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin—all states that Obama won—flipped from majority Democratic to majority Republican. The key was the defection of white working-class voters. Democratic congressional support among white working-class voters in Wisconsin went from six points Democratic in 2008 to 20 points Republican in 2010.

We had gotten the new voting groups right, but we were dead wrong about the Democrats’ ability to hold on to the working-class whites.

Democrats also lost six Senate seats and six governorships, and the main losses were in the industrial Midwest. While Democrats’ support fell across virtually all voting groups, the most consequential shift was among white working-class voters. The Democratic deficit among these voters ballooned to 23 points in 2010. And these voters were at the time close to half of all voters—and considerably more than half in the upper Midwest where a good deal of the carnage took place. We had gotten the new voting groups right, but we were dead wrong about the Democrats’ ability to hold on to the working-class whites.

Losing the Heartland

We also underestimated the Democrats’ difficulties in bridging a geographical and industrial divide that cut across America and that, in the 2010 election, became a political chasm. This Great Divide pitted the dynamic postindustrial metro areas of the country against the working-class areas in the small towns, rural communities, and midsize cities scattered across the Heartland that still depended upon manufacturing and resource extraction. This divide came to define the contest between the political parties in the 2010s.

In Ohio, the Democratic popular vote for the House fell from a five-point advantage in 2008 to a 12-point deficit in 2010. Five Democratic incumbents were tossed out of office as a red wave swept across the state. Consider Ohio’s Sixth Congressional District that runs along the southeast side of the state and borders Kentucky, West Virginia, and Pennsylvania. The district goes from rural Lucasville through Athens and older Ohio River industrial towns and eventually reaches the Youngstown city limits. It was the home to steel and auto plants and to coal-fired power plants. Incumbent Democrat Charlie Wilson, who had carried the district by 30 points in 2008, lost to Republican Bill Johnson by five points in 2010.

These areas were once the center of Democratic Party strength, but now, along with rural areas, they were becoming part of the Republican base.

And what happened there happened in other districts that were heavily dependent on manufacturing and mining. These areas were once the center of Democratic Party strength, but now, along with rural areas, they were becoming part of the Republican base.

In 2012, Obama easily defeated Mitt Romney, who had opposed the auto bailout and allowed the Democrats’ presidential candidate to run as the candidate of the common man and woman and to revive the image of Republicans as the party of the uncaring rich. But Republicans retained control of the House of Representatives and, in the 2014 elections, the Democrats’ weakness among the white working class and on one side of the Great Divide reemerged with a vengeance. That year, the Democrats lost 13 House seats and a stunning nine Senate seats and suffered major losses at the state level. The key to these losses was once again the defection of the white working class, with the national deficit among these voters increasing to 25 points.

Trump’s Telling Victory

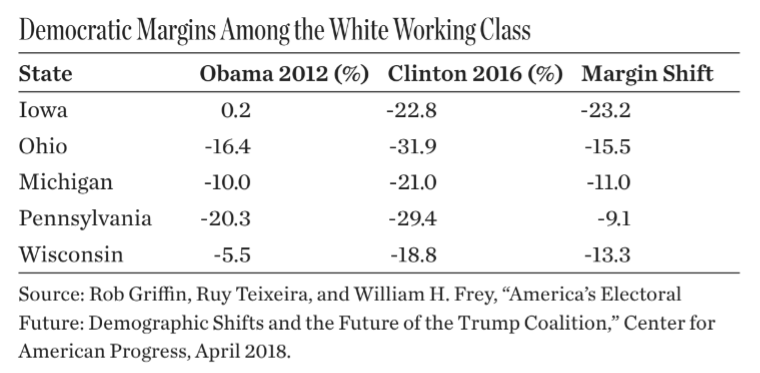

In 2016 our forecast of Democratic success among professionals, single women, and minorities held. Clinton increased the Democratic margin among white college-educated voters by six points from Obama’s victory in 2012. But white working-class voters are far more numerous than their college-educated counterparts, particularly in the midwestern states where the election was decided. And Clinton’s deficit among these voters became the most important factor in her completely unexpected defeat by Donald Trump. In the country as a whole, the Republican advantage among white working-class voters increased six points to a staggering 31 points.

Counties that shifted strongly toward Trump tended to be dominated by working-class whites and dependent on industries battered by automation and international trade.

The Great Divide also widened from 2012. Counties that shifted strongly toward Trump tended to be dominated by working-class whites and dependent on industries battered by automation and international trade. In addition, many of these communities had seen declines in civic life and increases in deaths from alcoholism, drug abuse, and suicide. In 2012, Obama had won rural Howard County in Iowa by 21 points. In 2016, Clinton lost it by over 20 points. In 2008 and 2012, Obama had won Clinton County in eastern Iowa, a manufacturing center with big employers like Archer Daniels Midland, by 23 points. But in 2016, the county swung by a massive 28 points toward Trump and the GOP, giving him a 5-point advantage over Clinton.

It was much the same story in Ohio, Pennsylvania, and other Rust Belt states, where voters in working-class counties abandoned by industrial employers shifted massively to the GOP. Obama had carried Ohio’s Trumbull County, anchored by the formerly prosperous and now opiate-plagued industrial town of Warren, by 23 points in 2012. But Trump carried the county by six points in 2016. Obama had carried Luzerne County, centered on the blighted industrial town of Wilkes-Barre in northeastern Pennsylvania, but in 2016 Trump blew out Hillary Clinton in the county by 19 points.

The Mythic Majority-Minority

While we were rethinking our theory of an emerging Democratic majority, some Democratic theorists were doubling down on the theory. They argued, citing Census projections, that while working-class whites were abandoning the Democratic Party, minority populations, expected to become a majority of the population by 2045, would ensure ever-easier Democratic victories. If minorities were still voting three-quarters Democratic in 2045, this thinking went, Democrats would need only a little over 30% of the white vote to win elections.

There are two problems with this thesis. The first has to do with who is identified as “white.” In the Census, Hispanics and Asians are classified as minorities even if they are of mixed race and identify themselves as white. In most predictions of a “majority-minority” nation, the only citizens counted as white are those who identified as white and checked no other boxes. But high percentages of the children of mixed-race or ethnic marriages, one of whose parents is white, tend to identify as white. If what matters in politics is how voters identify themselves racially or ethnically, the effective size of the “white vote” is larger than the Census would indicate, and it’s likely to stay larger and for longer than Democratic strategists expect.

The second problem is that Democrats can no longer count on Hispanic and Asian voters. This was apparent in 2014, when Democratic strategists organized Battleground Texas on the assumption that by attracting the state’s Latino voters they would turn it blue. A test of this assumption was the state’s gubernatorial race that year, with Republican attorney general Greg Abbott, a hardline conservative, going against Democratic state senator Wendy Davis, who had acquired a national reputation when she staged a one-woman filibuster against a bill banning abortions after 20 weeks. Abbott routed Davis by 20 points while taking 44% of the Hispanic vote and carrying Hispanic men.

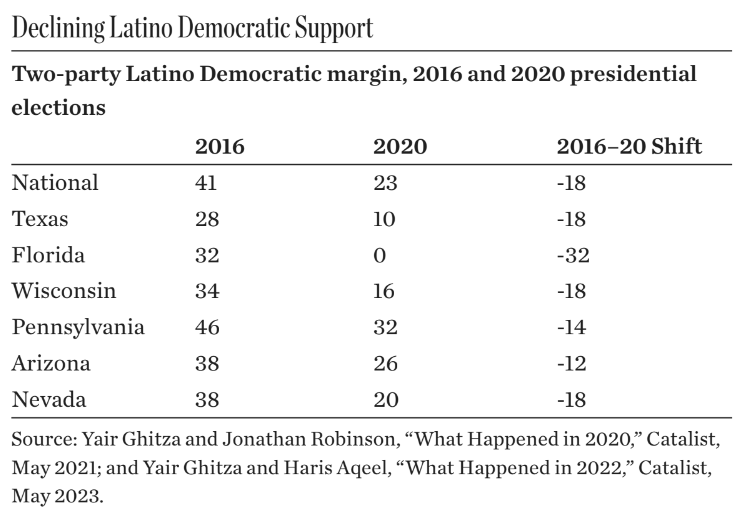

In 2020, Democrats assumed that they would easily win the Hispanic vote against a president with a history of vitriolic statements against Mexico and Mexican Americans and hostility toward illegal immigration, but Trump actually improved his vote with Hispanics from 2016.

In 2020, Democrats assumed that they would easily win the Hispanic vote against a president with a history of vitriolic statements against Mexico and Mexican Americans and hostility toward illegal immigration, but Trump actually improved his vote with Hispanics from 2016. The most notable results came in Texas. Trump got over 40% among voters in the predominately Hispanic border counties along the Rio Grande River, and he actually won Zapata County, which had not voted for a Republican presidential candidate since 1920. Republican Tony Gonzales won Texas’s 23rd Congressional District, which extends west from the outskirts of San Antonio and is 69% Hispanic. That district, which Clinton had carried in 2016, went for Trump.

Overall, Latinos in 2020 shifted sharply to Trump and reduced Democrats’ margin among this group by 18 points. Cubans had the largest shift of 26 points, but Puerto Ricans moved by 18 points to Trump, Dominicans by 16 points, and Mexicans by 12 points. Among Hispanics, the largest shifts were among working-class voters. According to a Pew analysis, Trump got 41% nationally of the working-class Hispanic vote.

In the presidential race, Democrats’ margin among Asian Americans seems to have held up—a result in part of Trump’s use of terms like “Kung Flu” to describe the COVID-19 pandemic. But in some congressional races, there were signs of Asian discontent with Democrats. In California’s heavily Asian Orange County, two Korean American Republicans defeated Democratic incumbents. Democrats continued to enjoy huge margins among Black voters, but even here, those margins declined in 2020 by five points relative to 2016. According to Catalist, Trump won 13% of Black men.

Latino men remained a clear weak spot for the Democrats, with 42% casting their House ballots for Republicans.

Democrats failed to gain back much ground nationally among Hispanic voters in the 2022 election, improving their margin relative to 2020 by just a point. Latino men remained a clear weak spot for the Democrats, with 42% casting their House ballots for Republicans. Working-class Hispanics posed a special problem, with the Democratic advantage among them falling 13 points from 2018. Compared to 2012, Democrats were down 20 points with the Latino working class.

In the states, Democrats’ support among Hispanics generally held steady in 2022, but not in Florida. In 2020, Biden had struggled to eke out just a tie among Florida’s Hispanic voters. Then, in the 2022 gubernatorial election, Ron DeSantis actually carried the Hispanic vote by 12 points, dominating the Cuban vote while splitting the Puerto Rican vote with Democratic candidate Charlie Crist.

In Texas, Republicans got 43% of the statewide House vote among Hispanics. Democrats’ poor showing in House races was the result of working-class Hispanics defecting to the Republicans. Democrats won college-educated Hispanics by 24 points, but working-class Hispanics made up three-quarters of the Texas Hispanic vote, and Democrats won this group by only six points statewide.

In New York City, the only precinct in Manhattan to vote for Republican gubernatorial candidate Lee Zeldin was in Chinatown.

Democrats have also suffered from defections among Asian American voters. In Virginia’s 2021 gubernatorial contest, Republican Glenn Youngkin got 44% of Asian votes. In New York’s 2021 mayoral contest, Republicans did 14 points better in heavily Asian precincts than they did in 2017. Asian voter defection was more broad-based in 2022 than in 2020. Nationwide, the Democratic advantage among Asian voters declined 13 points relative to 2020. And Asian voters in many urban neighborhoods seemed to be slipping away from the Democrats. In New York City, the only precinct in Manhattan to vote for Republican gubernatorial candidate Lee Zeldin was in Chinatown. In Brooklyn and Queens, Zeldin outpaced Democrat Kathy Hochul in the heavily Chinese 47th and 49th Assembly Districts and the 17th State Senate District in Brooklyn. Zeldin also won the 40th Assembly District in Flushing, which is dominated by Chinese and Korean immigrants.

In 2022, Democrats lost more ground among Black voters, compounding their losses from 2020. Republican House candidates won 12% of Black voters and 17% of Black men; the margin for the Democrats among the latter group fell by eight points compared to 2020. The Black decline, together with that among other nonwhites, appears to have been concentrated among working-class voters. From 2018 to 2022, the Democrats’ margin among nonwhite working-class voters declined 15 points. If you go back even further to 2012, the Democrats’ advantage among the nonwhite working class has declined 25 points.

Democrats aren’t just losing white working-class voters, then. They’re losing working-class voters, pure and simple.

Democrats aren’t just losing white working-class voters, then. They’re losing working-class voters, pure and simple. That has undermined the Democrats’ chances of being the majority party. It has also deprived the country of a party that could champion the average American against what Bernie Sanders called “the billionaire class” and bridge the Great Divide between growing metro areas and small-town America.

Instead, with the Republicans steadily losing ground among college-educated voters and in states with high-tech metro centers, the two parties are locked in an unstable stalemate and in culture wars that evade the great issues that will determine the country’s future, while growing numbers of voters express disillusionment with both parties.

Adapted from Where Have All the Democrats Gone? by John B. Judis and Ruy Teixeira, published by Henry Holt and Co., an imprint of Macmillan.

Recommended Reading

The Future of the Biden and Trump Coalitions

While Joe Biden will be the 46th President of the United States and Donald Trump will join the small club of incumbents who could not get re-elected, it’s fair to say that Biden’s triumph was not so overwhelming that it even begins to settle the question of which party will dominate the 2020s.

US Election: The Working Class is Up for Grabs

It’s now clear that Joe Biden will be America’s next president. While Democrats will undoubtedly celebrate this fact, the overall election results should give little comfort to them, given their failure to re-establish the party’s historically successful New Deal coalition, especially the working-class component.

The Limits of the Realignment

Not many talking points survived November’s narratological cull. The assumption that high turnout would crush Republicans down ballot turned out to be false, with both parties seeing a groundswell of Read more…