RECOMMENDED READING

American enthusiasm for a per-child family benefit has grown, but details matter and proposals differ widely—as do the programs already established in other nations. First comes the structural choice of direct payment or tax credit.

Direct payments can be disbursed monthly, but tax credits are generally delivered in an annual lump-sum payment once taxes have been collected, making the payment difficult to incorporate into a family budget.

Tax credits themselves come in two flavors: refundable or nonrefundable. Refundable credits are available to households in the full amount regardless of their tax liability—a family can get back more than it has paid in. Nonrefundable credits, on the other hand, can only reduce tax liability. As a result, lower-income households with little tax liability cannot always enjoy a credit’s full value.

Some family benefits provide larger payments when children are younger (generally aged 0 to 5 years). Some phase out for higher-income households, which requires policymakers to choose the threshold and rate at which the benefit declines, and whether a married couple can earn more than a single parent before the decline begins.

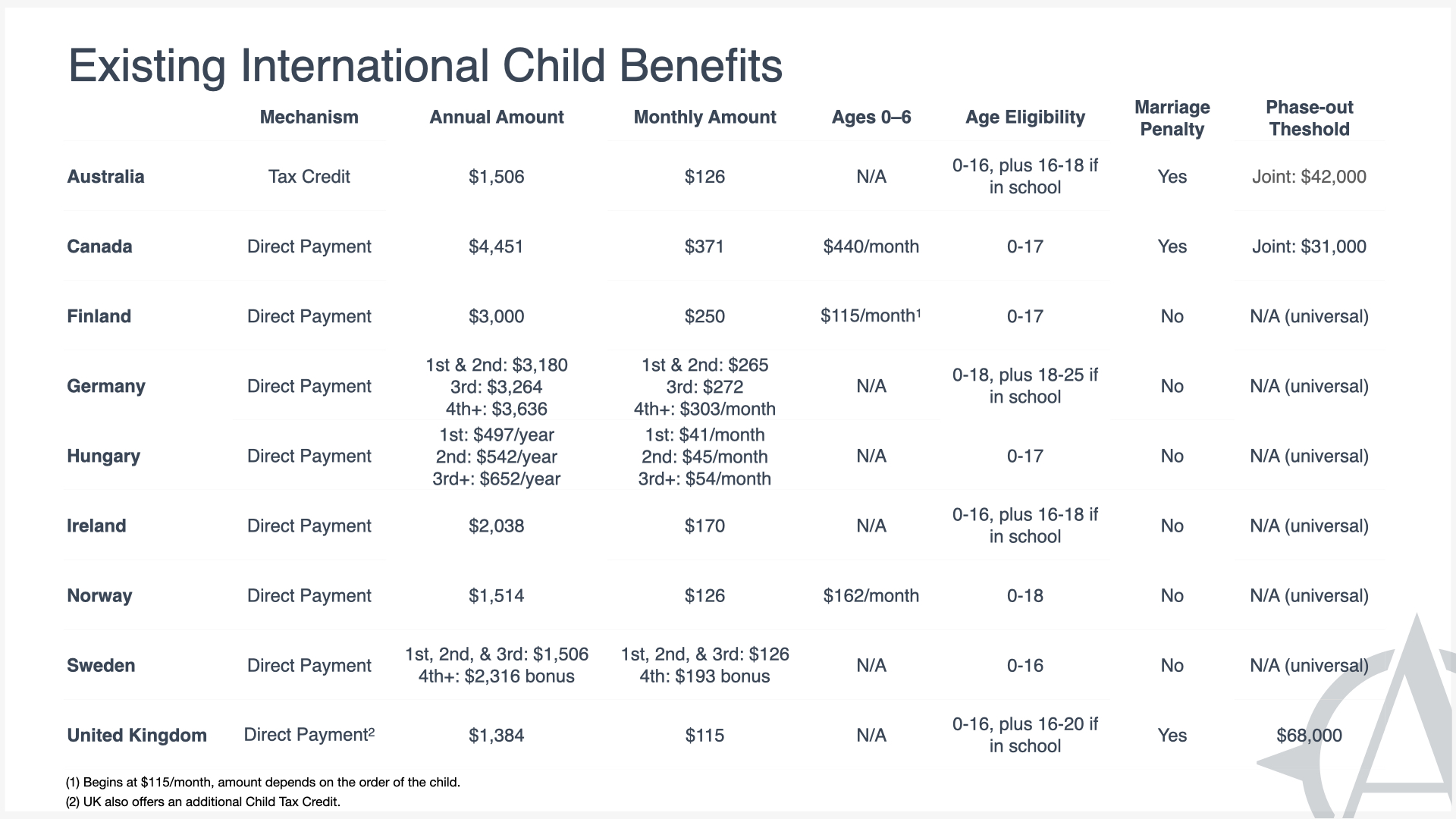

Canada has one of the world’s most generous family benefits, up to $371 per child per month, nearly $5,000 per year, until the 18th birthday. Canada’s benefit offers up to $800 more per year for children under 6. The program also offers an additional benefit to families raising children with serious disabilities, one of the only countries to include such a provision.

Sweden offers only $1,500 per child per year, regardless of age. But families with four or more children are eligible to receive an additional $2,300 per year. Sweden also offers over a year of paid parental leave and public daycare.

Hungary provides an array of family benefits as part of its efforts to encourage higher birth rates. Its family benefit program includes a scaled benefit system: Parents receive $500 per year for their first child, $540 per year for their second, and $650 per year for each additional child.

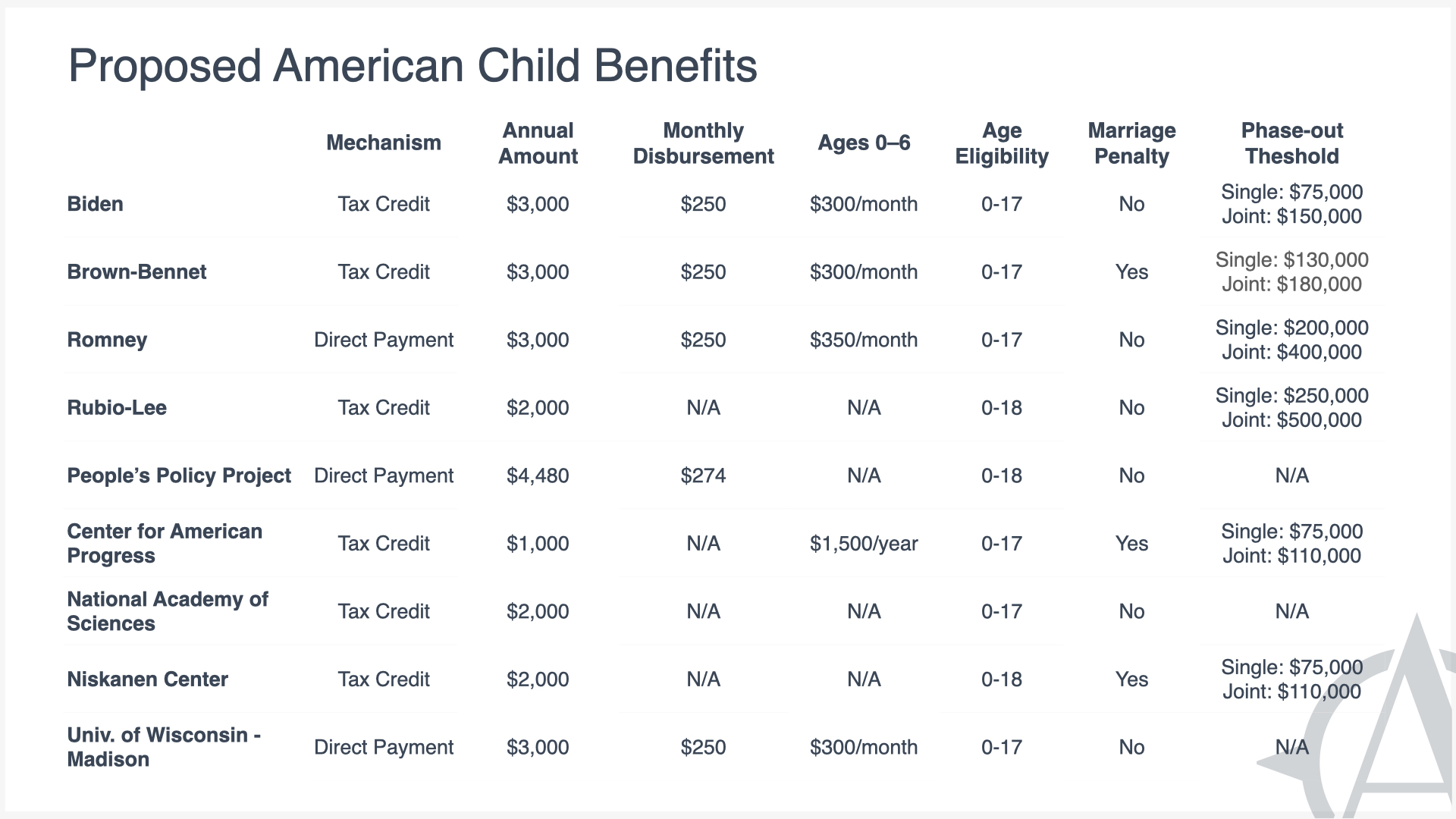

American proposals share several features with international programs. President Joe Biden, Senator Mitt Romney, and Senators Sherrod Brown and Michael Bennet all propose a monthly payment rather than the present lump-sum offered by the Child Tax Credit (CTC). Most American proposals pay an increased benefit for children under the age of 6.

President Biden has proposed a one-year expansion of the CTC. The credit’s value would increase from $2,000 to $3,000 per child per year, become fully refundable, and be paid monthly by the IRS. For children under 6, the value would be $3,600 per year. The Biden plan would eliminate marriage penalties, phasing out the benefit for individuals at $75,000 in annual income and for couples filing jointly at $150,000. The American Family Act (AFA), introduced by Senators Brown and Bennett, is quite similar to Biden’s proposal but would be permanent. The AFA would lower the present phase-out thresholds to $130,000 and $180,000, retaining an implicit marriage penalty, as the single filer threshold is not doubled for the joint filers.

Senator Mitt Romney’s proposal, the Family Security Act (FSA), differs in several ways from President Biden’s proposal. Romney’s plan is slightly more generous, offering an annual per-child benefit of $4,200 for children under the age of 6 and starting the payments 4 months before a child is born. Romney eliminates the CTC and provides the benefit as a direct monthly payment. The FSA would not phase out until a much higher threshold: $200,000 and $400,000 for single and joint filers, respectively.

International programs and American proposals differ in striking ways. First, the American benefits are more generous. England and Australia, for instance, offer a maximum of $1,400 and $1,500 per year, respectively – half the amounts proposed by Biden and Romney. Even Sweden, with its generous welfare state and wrap-around services, offers just $1,500 per year. But what these international plans don’t offer in generosity, they make up for in universality. Whereas most existing child benefit programs, particularly those in continental Europe, go to all citizens regardless of income, American policymaker all propose a means-tested phase-out.

Second, unlike any American proposal, several European programs are explicitly pro-natal, offering an increased benefit for each additional child. For instance, Germany increases the amount provided for families having three or more children, while Sweden provides a bonus for families with four or more children. As with means-testing, American policymakers will likely be guided in their own design choices by both their concrete objectives and their sense of what the American people will find politically palatable.

Recommended Reading

Romney, Hawley, Rubio, and Lee’s Building Blocks for Family Policy

The key parameters for understanding competing family-benefit proposals.

Policy Brief: A Monthly Family Benefit

Help working families with the costs of raising children

Is a New Entitlement Program the Solution for Working Families?

How does the Fisc stack up? Better than a universal child allowance, though I still have concerns.