RECOMMENDED READING

Matt poses some important questions below about how conservatives must defend anti-corruption statecraft against (tellingly) American libertarians and Chinese communists. I think it is right to suggest that the founders and their generation generally shared a robust sensibility that opposing, combating, and defeating corruption was properly political activity at the regime level.

I also think it’s right to suggest that critics of anti-corruption politics tend to turn their arguments on the idea that anti-corruption politics is always a politics of virtue: no matter how much we dislike the corruption of politics, the politics of virtue is much more dangerous. The critics of anti-corruption politics are apt to treat the dangers of enforcing public and private virtue quite similarly. Consider the debate over integralism, where many critics end up at a level of argument where if we pass laws restricting access to pornography, we’ll soon be jailing women who wear jeans instead of skirts!

Of course this is a different kind of political argument over corruption than the one Matt is inviting us into. Matt is concerned with the problem that power corrupts, and wants conservatives to get more rigorous about understanding how public virtue can cure this ill. Critics are apt to attack this position by conflating, or arguing that it is impossible to keep separate, public virtue aimed at the corruptions of power on the one hand and, on the other, publicly enforced private virtue aimed at the corruptions of the soul.

Complicating the picture is that many on the Left now demand that the state enforce their private notions of virtue ethics against whiteness and other phenomena, expressly on the basis that the phenomena inseparably blur together institutional and individual corruption.

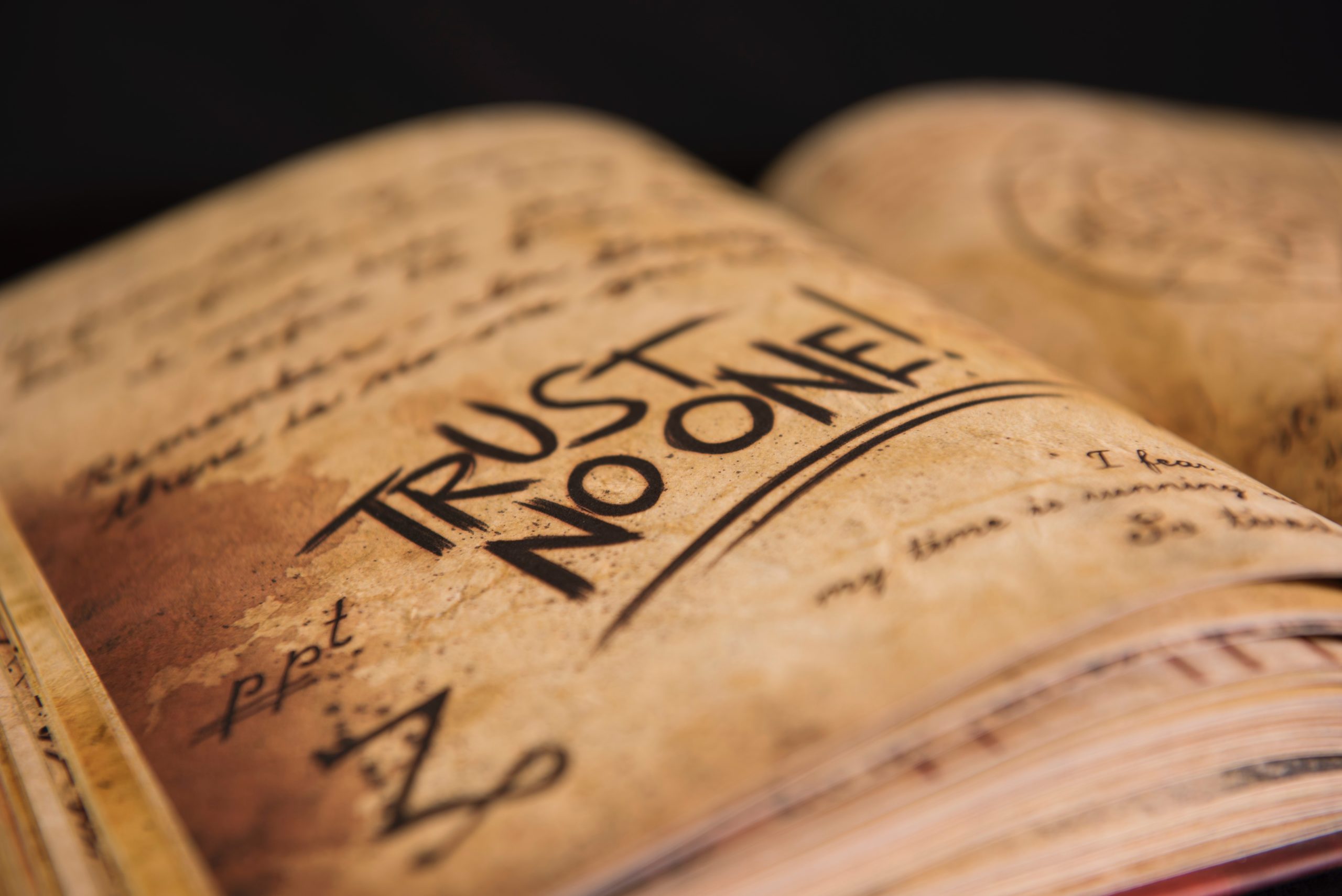

But there is a simple way to understand how political and private virtue differ. When it comes to statecraft the foundational virtue is to know and be able to discern the difference between friends and enemies, those who love you versus those who hate you. This is not the foundational private virtue. The health or salvation or your soul may well depend on a clear grasp of good versus evil, but Christianity and other moral doctrines offer specifically non-political teachings about how to treat your enemies. So what the critics of anti-corruption politics really want to argue is that even the political power to discern friends versus enemies and treat them that way is so corrupting that it causes statespersons to wrongly and harmfully import their private morality into their discernment and treatment of friends and enemies.

What is interesting is how difficult it is to distinguish this argument from the critics’ own interest in denying, when it comes to policymaking, the significance or even the existence of friends and enemies. Some (certain American libertarians) may do this ingenuously, others (certain Chinese communists) disingenuously, but in both cases they conspicuously rally the virtue rhetoric of global solidarity and world togetherness in order to give it an impartial appeal. The post-partisan libertarian and the Party communist are in this sense both at serious risk of presenting politics itself as a problem, perhaps the ultimate problem–a crime, by defective souls against both private and public virtue rightly understood, which only post-political policymakers are enlightened enough not to commit.

Conservatives, but surely not just conservatives, ought to be able to stand incontrovertibly against these oddly similar anti-political ethical positions.

Recommended Reading

Trickle-down Distrust

In his recent post Matt Stoller observes that a common theme at The Commons thus far is “the reemergence of the state as the key locus of legitimacy for the exercise of power” and urges conservatives to think about corruption and statecraft. What’s needed, he says, “is a vision of how to structure such a state without succumbing to corruption.”

Whither Corruption and Conservatism?

Oren Cass invited me to contribute to this site not as a conservative but as a lefty and Democrat who is fascinated by the project of intellectual revival in which this network of thinkers is engaged.

Why the Free Trade Debate Needs the Real Adam Smith

Oren Cass is right to note that modern economists largely misunderstand Adam Smith. But the misunderstanding runs deeper and traces even further back than editorializing in 20th-century textbooks. For more than two centuries, scholars have ignored the relationship between Smith’s political philosophy and economic analysis.