RECOMMENDED READING

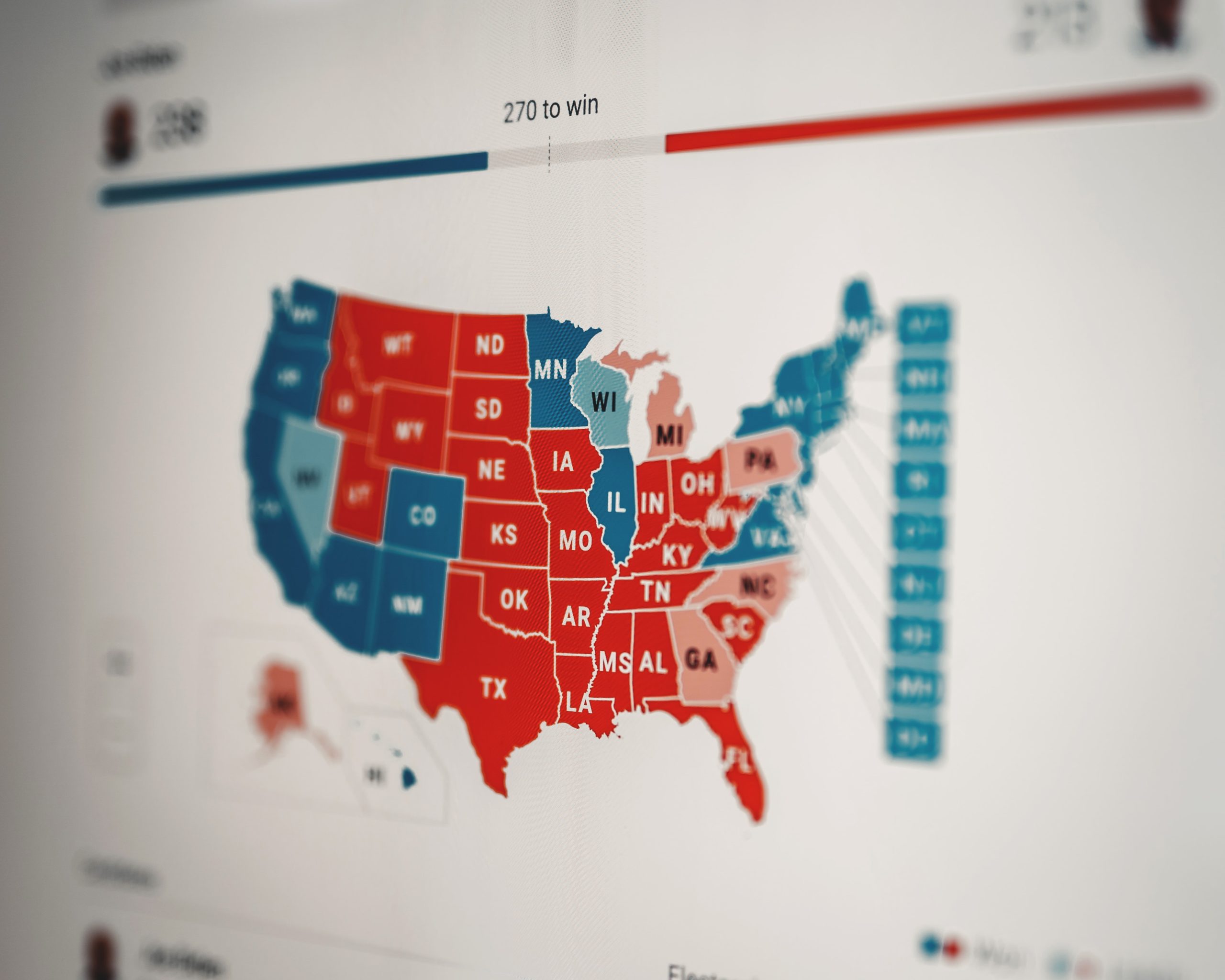

It’s now clear that Joe Biden will be America’s next president. While Democrats will undoubtedly celebrate this fact, the overall election results should give little comfort to them, given their failure to re-establish the party’s historically successful New Deal coalition, especially the working-class component. If any election was ripe to reconstitute this coalition that sustained the Democrats electorally for decades, it was this one. But the most striking takeaway from the 2020 election is how much it mirrors the results of the 2016 election, literally give or take the shift of a hundred thousand votes or so in a few key Rust Belt and Sun Belt states. Another thing that should give Democrats pause is that despite Trump’s direct appeals to racist fears, more than a quarter of his votes came from nonwhite Americans, the highest percentage for a GOP presidential candidate since 1960.

It wasn’t supposed to be this close. Against the backdrop of a pandemic, depression-like levels of unemployment, and a president whose approval rating never rose beyond 50% during his entire time in the White House, 2020 created what should have been the ideal conditions for a so-called “blue wave”, both nationally and in the state houses. But the coattail effect has been minimal (ironic, considering that this was one of the ostensible rationales for Democrats selecting a moderate like the former Vice President, as opposed to a progressive, such as Bernie Sanders). By the same token, the GOP will likely retain control of the Senate, and while the Democrats will keep their majority in the House of Representatives, they have lost at least six seats, possible more. Nobody in the punditocracy saw that one coming.

American voters may have rejected Trump, but they weren’t buying what the Democrats were selling. Longstanding concerns such as “precarity”, a condition reflecting intense economic insecurity were largely left unaddressed. And this problem has been exacerbated by the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic.

Over the past few election cycles, it has become increasingly clear that America’s traditional party coalitions have come asunder, increasingly challenging our traditional ideas of what it means to be a Democrat or a Republican. Specifically, in the case of the Democratic Party, both Wall Street and Silicon Valley elites have largely seized control of the party’s policymaking apparatus, a byproduct of which has been the evisceration of the party’s historic links with organized labor (at least what’s left of it).

And it’s no longer just the proverbial white working-class voters in the Rust Belt. Quite the contrary in fact: the 2020 election showed a significant erosion in Hispanic support for Biden in key states, such as Texas and Florida, and corresponding gains for the Republican Party, including working-class Hispanics. This undercuts the “demographic destiny” arguments made by figures such as Steve Phillips of the Center for American Progress, who wrote that “[t]he concerns of people of color should be driving politics today and into the future.”

In fact, the 2020 results have enhanced the opportunities for the Republicans to become a more broadly-based multiracial party of blue-collar conservatism. It is true that the GOP’s own historic corporate constituencies may well limit the party’s ability to grab this low-hanging political fruit. On the other hand, if trade and fiscal policy are ultimately married to national security concerns, it is conceivable that the GOP could build on the multiracial gains witnessed in this year’s election. A Hamiltonian national industrial policy married to a “Cold War 2.0”—in other words, an updated version of the kind of “military Keynesianism” deployed by Ronald Reagan in the mid-1980s—could conceivably consolidate the GOP’s efforts to become a party of an increasingly multiracial working class.

That also means that playing a game of political obstruction in order to make Biden a one-term president might prove risky for the GOP, especially given the fact that the country faces even more extreme challenges than it did when President Obama took over in the wake of the 2008/9 global financial crisis. Mitch McConnell remaining as the likely Senate Majority Leader could well lead him to conclude that his party paid no real political price in the 2020 election, even with the refusal to extend relief after the expiration of the CARES Act. On the other hand, champions of blue collar conservatism, such as Senators Marco Rubio and Josh Hawley, will likely find that their presidential aspirations will be frustrated if they connive with a strategy that promotes gridlock and policy inaction.

The bottom line is that working-class support is up for grabs for both parties. This is a development that should be welcomed by American workers. Far better to have both parties aggressively competing for working-class support by offering policies that actually address their concerns, as opposed to having it monopolised by one party – the Democrats – who have long taken that support for granted and done nothing to address those problems for decades. Trump might indeed be gone, but the GOP would be wrong to ignore some opportunities opened up by the president over the past 4 years.

Recommended Reading

The Future of the Biden and Trump Coalitions

While Joe Biden will be the 46th President of the United States and Donald Trump will join the small club of incumbents who could not get re-elected, it’s fair to say that Biden’s triumph was not so overwhelming that it even begins to settle the question of which party will dominate the 2020s.

The Receding Democratic Majority

Demography may be destiny, but its party affiliation is not

A New Coalition, if You Can Keep It

As the pundits, campaigns, and lawyers continue to unpack this election, there are a few things we know for certain.