RECOMMENDED READING

A group of exceptionally talented young engineers is preparing to launch a new company. They have two possible business plans: In one, they develop an app called BooBoo that allows a user to hire a stranger to jump out from behind a tree and scare the user’s friend, recording video of the incident and sharing it online. In the other, they commercialize a new material called SteelSeam with the potential to reduce home-construction costs by 20 percent. Assuming potential paydays of equivalent value for the founders, does it matter which one they pursue? Not to the market.

The market is very good at some things, ill-suited to others. It excels, for instance, at helping buyers and sellers determine the price at which supply of some commodity will match its demand. It is inappropriate for divvying up chores in a marriage or raising an army to beat back an invasion. The task of allocating capital falls somewhere in between. The market gives investors every incentive to maximize their private return and efficiently facilitates their efforts. But those incentives are a function only of the private costs and benefits associated with an investment—how much profit can the business generate how quickly, with what required capital and what risk? No economic theory holds that the attractiveness of a choice will correlate with its value to the society.

Note: This is the opening statement in a four-part debate with Duke University’s Michael Munger.

Recommended Reading

Could Baby Bonds Help Reduce Wealth Inequality in America?

American Compass’s Oren Cass, Senator Cory Booker, and other experts discuss the feasibility of government baby bonds.

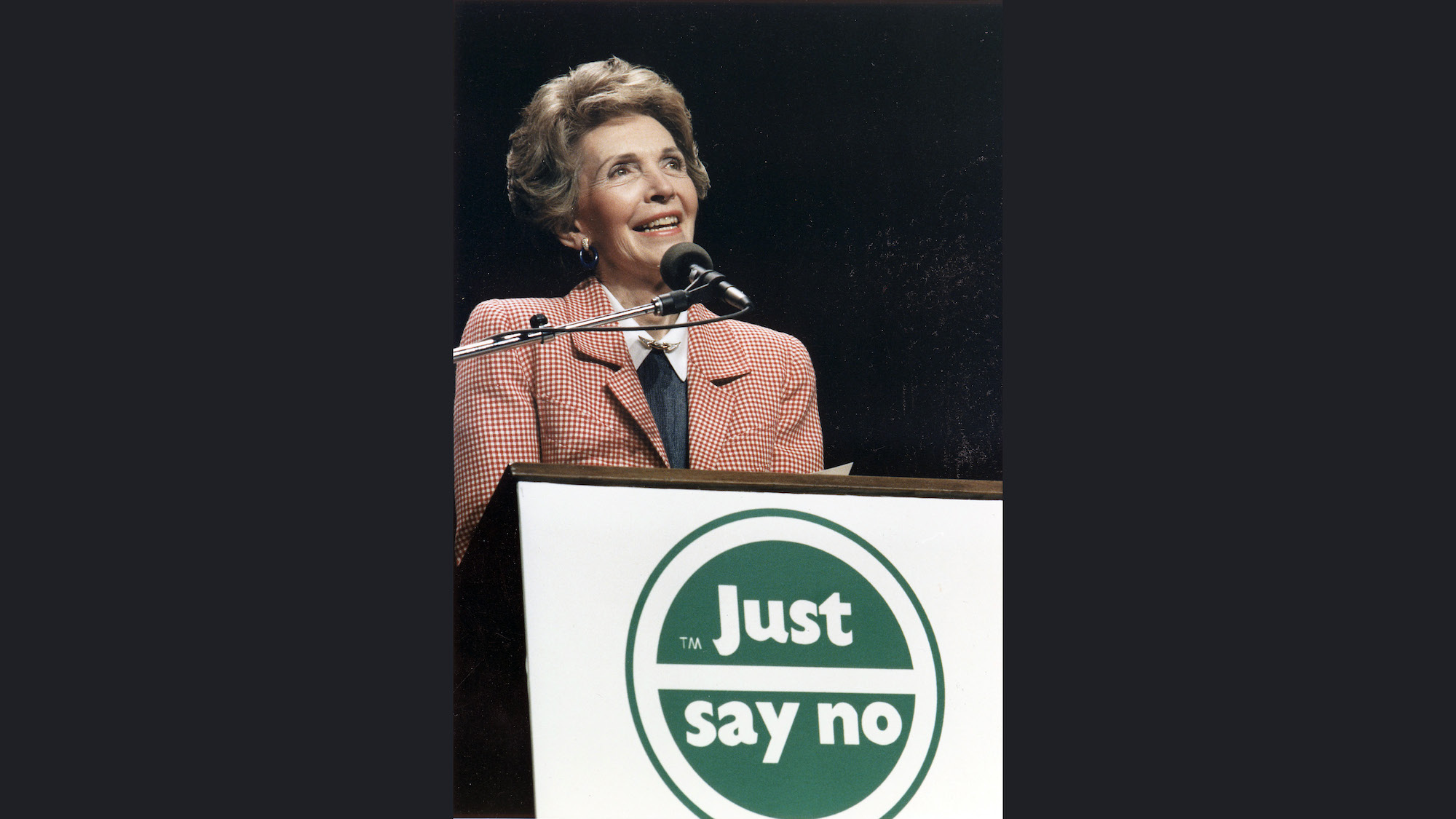

Just Say No to Rejoining TPP

Economic theorists treat globalization as the free market’s natural end state. But trade practitioners know that the opposite is true—that efforts at stitching together the world’s economies are among the messiest sausage-making exercises in policymaking.

Is There a Way of Doing Bipartisan National Industrial Policy?

The likely configuration of the new Senate represents a potential obstacle toward some of the grander Democratic Party policy visions outlined in President-elect Biden’s program.