A journey to the center of the neoliberal dogma

RECOMMENDED READING

In the fall of 2001, as the World Trade Organization prepared to welcome China, I was completing my introductory college economics course. I had mastered the basics of supply and demand, opportunity cost, indifference curves, and comparative advantage. A few days before China’s formal accession, I composed my first policy memo on the merits of free trade.

I still have the paper, written in the confident and unquestioning tone that my freshman self thought appropriate for a practitioner of the economic sciences, though with hindsight it seems more the tone of a recent convert to a fundamentalist sect, which I suppose I was. “There is no question,” I began, “that free international trade increases a society’s economic surplus.”

I dismissed concern for “a short-term loss in jobs” because “those labor resources can be quickly shifted to the production of goods to be consumed domestically (total domestic surplus has increased), or to goods that can be exported to now-wealthier trading partners.” I averred that, “damage to a given industry is more than compensated for by advancements elsewhere.” I even provided a parenthetical citation: “(Krugman).”

If memory serves, I got an A. For demonstrating mastery of the course material, this was fair. Held to a standard of correctness, though, I surely deserved an F.

Economic reality was in the process of disproving decades of economic theory. America was about to lose millions of jobs to the “China Shock” of cheap imports flooding the domestic market; those labor resources could not quickly shift to other jobs, though many did shift onto ballooning disability rolls or slide into drug addiction. Production did not shift quickly to other goods for domestic consumption: industrial production rose 94% from 1980 to 2000, but only 7% from 2000 to 2020; excluding the notoriously mismeasured production of semiconductors, American industrial output in the 21st century has declined by 10%. Nor did it shift to other goods for export: even in advanced technology products, those two decades saw a healthy American trade surplus collapse into a yawning deficit. (These data use the 2020 rate of output pre-pandemic.)

Such statistics were the trees in a forest of economic stagnation. Globalization was supposed to supercharge growth, which instead slowed. Productivity growth stalled, and manufacturing productivity logged six straight years of decline. Business investment fell to the lowest share of GDP on record and financial markets withdrew trillions from the productive economy. America lost its ability to make the world’s fastest computer chips or jetliners that would safely fly. Rather than transition to well-paying “jobs of the future,” America’s labor market produced jobs requiring a college degree only half as fast as it added college graduates. For the vast majority of Americans, working in jobs that did not require a degree, wages stagnated.

I spent the 2000s blissfully unaware of all this, dutifully completing more economics courses, becoming a management consultant, and then attending law school, as one does. But in the summer of 2011, I went to work for presidential candidate Mitt Romney and received the assignment to prepare his briefing on trade policy.

I still have the PowerPoint presentation, with its crisply outlined free-trade agenda, its lead message that “opening new markets is crucial to economic growth and job creation, and the WTO is the best hope for efficiently opening markets around the world,” and its highlighted bottom line: “Give workers a growing economy, and the tools to participate in it.” Romney’s response, after reviewing the materials, remains vivid in my mind: “That’s fine. But what are we going to do about China?”

What are we going to do about China? It was not a question one asked in polite company back then, for fear of being revealed as an economic simpleton or, worse, a protectionist. Despite this, or perhaps because of it, the question fascinated me. Determined to find my boss an answer, I soon encountered two challenges.

First, the right-of-center’s leading free-market economists and trade experts had no interest in the question, let alone interesting answers. Dissidents found little purchase in the debate. Politicians like Patrick Buchanan and Ross Perot were mocked as charlatans—or worse. Serious analysts like Dani Rodrik, a Harvard University political economist; Clyde Prestowitz, a trade official from presidential administrations of both parties; and Robert Lighthizer, a trade lawyer and former deputy U.S. Trade Representative under President Reagan, were considered heretics—intellectual curiosities at best. The labor movement’s concerns were dismissed as special interest lobbying, and broader critiques from the left were presumed to be anti-capitalist.

“What are we going to do about China? It was not a question one asked in polite company back then, for fear of being revealed as an economic simpleton or, worse, a protectionist.”

Second, the problem was much bigger than just China. The entire edifice of globalization—the case for the unfettered flow of goods, people, and capital across borders—was built upon the firm faith that more of these things was always better. This free-trade dogma possessed a compelling internal logic, but it insisted explicitly on unconditionality. Paul Krugman provided a clear statement of the principle in 1997: “The economist’s case for free trade is essentially a unilateral case. A country serves its own interests by pursuing free trade regardless of what other countries may do.”

According to this model, as economists had been taught and now themselves taught, free trade was and would always be America’s optimal strategy. If China wanted to steal our intellectual property, manipulate its currency, subsidize state-owned enterprises, and sell us the results for cheap, they were the suckers and we should just enjoy all the stuff. If China took back our financial assets instead of our exports, accepting IOUs in return for sending us products we might once have made ourselves, all the better. Excoriating the strong stance Romney ultimately took on trade, the Wall Street Journal’s editorial board concluded that what would truly be in America’s “national interest,” rather than confronting Beijing’s mercantilism, was helping the Chinese Communist Party “liberalize its financial system and allow the free flow of capital.”

The model could not countenance an exception for China, which meant that if the model failed there, then it had failed altogether. The absolute confidence of the economists would be foolhardy; policymakers would have to start asking under what conditions globalization might promote prosperity and they would need tools to use when those conditions were not met. The more I dug, the more clearly I saw the foundation’s rot, and the more obvious it became that the edifice was doomed to crumble no matter how loudly economists attested to its strength.

But why was the model wrong? Hadn’t Adam Smith shown that the invisible hand would ensure that people pursuing their self-interest also advanced the public interest? Wasn’t this the premise of capitalism? Policymakers would need to answer those questions if they hoped to address the problem rather than just lament it, or make it worse. Over the past decade, I’ve been trying to find my own answers.

My conclusion is that we have gotten capitalism wrong and that globalization, far from its logical endpoint, is its antithesis. Capitalism does not work because people with capital, left to their own devices to maximize profits, will behave in ways that deliver widespread prosperity. That’s nonsensical and has not a shred of evidence to support it. Nor is “capitalism” a synonym for “economic freedom,” notwithstanding the canon of market fundamentalism. Capitalism works because, under a specific set of conditions in a well-governed market, capitalists need increasingly productive workers to achieve increasing profits, and workers need access to capital to achieve increasing wages, and in their mutual dependence both find it in their interest to act in ways that deliver good outcomes for themselves and for consumers as well. Capitalism locks everyone in a room together and encourages them to find a way out.

“My conclusion is that we have gotten capitalism wrong and that globalization, far from its logical endpoint, is its antithesis. Capitalism does not work because people with capital, left to their own devices to maximize profits, will behave in ways that deliver widespread prosperity. That’s nonsensical and has not a shred of evidence to support it.”

This system of mutual dependence between capital and labor, not mere “economic freedom,” is what Adam Smith so ably described. Globalization destroys it, instead urging the owners of mobile capital to forsake the interests of their fellow citizens and search for higher profits through labor arbitrage abroad. A democratic republic’s vast working and middle classes will rightly reject such an arrangement, forcing elites to choose between restoring capitalism by constraining capital or entrenching their own economic prerogatives by subordinating the democratic process. That’s as good a description as any of the precipice at which America now stands.

The Invisible Hand Disappears

Given the extraordinary degree of confidence that economists and policymakers express about the wisdom of globalization, I had expected to encounter a compelling and well-theorized case in its favor. Instead, I found a collective, jingoistic misunderstanding of the 200-year-old writings of Adam Smith and David Ricardo. Of course, those great political economists had many insights that remain relevant today. But their theories were being applied out of context, in ways they never could have imagined, and without concern for the specific warnings they did provide. The case for globalization wallowed in market fundamentalism because no better work had been done.

A 2007 report from The Economist summarized well the state of its eponymous profession:

Globalisation is a big word but an old idea, most economists will say, with a jaded air. The phenomenon has kept the profession’s number-crunchers busy, counting the spoils and how they are divided. But it has left the blackboard theorists with relatively little to do. They are confident their traditional models of trade can handle it, even in its latest manifestations.

To illustrate the point, the magazine quoted the conclusion of Greg Mankiw, Harvard University economist and recent chairman of President George W. Bush’s Council of Economic Advisers (CEA), that “services offshoring fits comfortably within the intellectual framework of comparative advantage built on the insights of Adam Smith and David Ricardo.”

This mode of thought was pervasive and bipartisan. “In the last decade of the 20th century,” Krugman advised in 1993, “the essential things to teach students are still the insights of Hume [a contemporary of Smith’s] and Ricardo. That is, we need to teach them that trade deficits are self-correcting … . If we can teach undergraduates to wince when they hear someone talk about ‘competitiveness,’ we will have done our nation a great service.”

“While Smith and Ricardo might be flattered that their work has attained the status of scripture—never modernized, always obeyed—they would certainly be aghast.”

The thinking persists. Javier Solana, once the European Union’s foreign policy chief and now a distinguished fellow at the Brookings Institution, defended globalization in 2020 with the observation that, “Adam Smith’s axioms about specialization, and David Ricardo’s regarding comparative advantage, are as true today as they were 200 years ago.” Earlier this year, Glenn Hubbard, dean emeritus at Columbia Business School and Mankiw’s predecessor at CEA, published a book marketed by Yale University Press as “taking Adam Smith’s logic to Youngstown, Ohio” to “promote[] the benefits of an open economy.” National Review published an essay adapted from the book under the title, “The Enduring Logic of The Wealth of Nations.”

While Smith and Ricardo might be flattered that their work has attained the status of scripture—never modernized, always obeyed—they would certainly be aghast. Both were brilliant analysts who understood that economic principles were contingent on social conditions, and who carefully enumerated the conditions relevant to their analysis. Indeed, seeing as they were not writing about and could not possibly have comprehended 21st-century globalization, it is a particular testament to their intellect that they nonetheless anticipated and disclaimed a feature of our modern economy: the free flow of capital. Their theories applied, they both insisted, only so long as a nation’s capitalists invested within its own borders.

Start with Smith and his famous “invisible hand,” Exhibit A in the classic account of capitalism. The metaphor stands today for the idea that market forces ensure people pursuing their own profit behave in ways that benefit society broadly. It is “the hand of free commerce that brings magic order and harmony to our lives,” in the words of libertarian author Amity Shlaes.

That’s not what Smith meant. For all its quotation, the phrase appears only once in the two volumes of The Wealth of Nations (1776), in a sentence that begins, “By preferring the support of domestic to that of foreign industry…”

By preferring the support of domestic to that of foreign industry, he intends only his own security; and by directing that industry in such a manner as its produce may be of the greatest value, he intends only his own gain, and he is in this, as in many other cases, led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention.

They don’t teach all that in Economics 101. To the contrary, as Jonathan Schlefer, longtime editor of MIT’s Technology Review once exposed, the leading economics textbook of the 20th century edited most of it out. In Economics, Nobel laureates Paul Samuelson and William Nordhaus reprinted the quote as, “He intends only his own security, only his own gain. And he is in this led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention.” Students are not even given an ellipse.

Smith’s actual theory assigned enormous caveats to the idea that capitalists pursuing their own interests will behave in ways beneficial to the broader society. Building to his description of an invisible hand, he observed that, “every individual endeavours to employ his capital as near home as possible as he can, and consequently as much as he can in the support of domestic industry,” in part because, “he can know better the character and situation of the persons whom he trusts, and if he should happen to be deceived, he knows better the laws of the country from which he must seek redress.” Smith continued, “Upon equal, or only nearly equal profits, therefore, every individual naturally inclines to employ his capital in the manner in which it is likely to afford the greatest support to domestic industry, and to give revenue and employment to the greatest number of people of his own country.” Immediately following the hand’s debut, he specifies that the businessman can best determine “the species of domestic industry which his capital can employ” (all emphasis added).

Neither “magic” nor inevitable, Smith’s argument for an alignment of self-interest with the public interest is a logical deduction built upon clearly stated preconditions. If a capitalist wishes to deploy his capital domestically, and if the domestic investment that will generate the most profit for him is also the one that will create the most value and employ the most people in his country, then we will have a well-functioning capitalist system.

David Ricardo managed to be even more explicit. Modern economists cite fondly the seminal example in his Principles of Political Economy and Taxation (1817), which described England trading cloth to Portugal for wine. The trade will be beneficial to both sides, Ricardo showed, even if Portugal can produce both cloth and wine more cheaply. This idea of “comparative advantage,” suggested Paul Samuelson (he of the mangled Smith quotation), is the only principle of the social sciences that is both true and nontrivial.

But like Smith, Ricardo saw that his model required capital to be constrained. His example only works, he emphasized in the very next paragraph, because of “the difficulty with which capital moves from one country to another.” Where Portugal is the low-cost producer of both, “it would undoubtedly be advantageous to the capitalists of England and to the consumers in both countries, that under such circumstances, the wine and the cloth should both be made in Portugal, and therefore that the capital and labour of England employed in making cloth, should be removed to Portugal for that purpose.” Echoing Smith, he noted that this does not happen in practice because, “the fancied or real insecurity of capital, when not under the immediate control of its owner, together with the natural disinclination which every man has to quit the country of his birth and connexions, and intrust himself with all his habits fixed, to a strange government and new laws, checks the immigration of capital.”

“In short, Smith and Ricardo stated their propositions in terms incompatible with modern globalization. Both assumed that capital would remain in the domestic market. And as a corollary, both conceived of trade as occurring only on the basis of goods for goods.”

Ricardo then went further than Smith, from positive statements about how the world does work to a normative one about how it should: “These feelings [of allegiance to a nation], which I should be sorry to see weakened, induce most men of property to be satisfied with a low rate of profits in their own country, rather than seek a more advantageous employment of their wealth in foreign nations” (emphasis added).

In short, Smith and Ricardo stated their propositions in terms incompatible with modern globalization. Both assumed that capital would remain in the domestic market. And as a corollary, both conceived of trade as occurring only on the basis of goods for goods. In Ricardo’s telling, England “purchase[s wine] by the exportation of cloth.” Smith posited that “if a foreign country can supply us with a commodity cheaper than we ourselves can make it, better buy it of them with some part of the produce of our own industry.”

To march confidently forward with modern globalization on the basis of Smith and Ricardo is an act of spectacular hubris, equivalent to consulting a treatise on flight that describes how objects can defy gravity if an engine delivers sufficient thrust and an airfoil delivers sufficient lift, then wantonly shoving passengers off a cliff in metal boxes. At least, in that case, most people would stop after the first few bodies piled up. Our economists wave their manuals and shout, “Congratulations, you’re flying!”

A Trade Theory in Motion

The enormity of the intellectual failure invites speculation of global conspiracy. The textbook literally rewrote Adam Smith’s theory. That the errors invariably compounded to the benefit of the wealthy, powerful, and cosmopolitan, at the expense of the typical American family and community, is enough to send one searching for the meeting minutes from whichever Illuminati subcommittee had jurisdiction.

But we should probably hesitate to attribute intention to something more easily explained by inertia and ideology. Expanding trade had proved beneficial for many generations, as economic theory had predicted. At the moment of transition, as ships and railcars laden with natural resources and agricultural products gave way to the post–World War II economy of multinational corporations, integrated supply chains, and international finance, the classical model appeared to hold for globalization generally. Its strict assumptions about immobile capital, and goods exchanged for goods, seemed unnecessary. “Until the 1970s,” observes Hubbard, “both industry and labor in the United States prospered, with little foreign competition. This success made it easier for the United States to play a leading global role in championing openness to globalization and trade.”

Rather than recognize that a particular set of conditions had supported the desirable outcomes, economists concluded that markets delivered such outcomes automatically—that with greater globalization would always come greater benefits. In The Constitution of Liberty (1960), Friedrich Hayek criticized those who “lack the faith in the spontaneous forces of adjustment” and he promoted instead the “attitude to assume that, especially in the economic field, the self-regulating forces of the market will somehow bring about the required adjustments to new conditions.” As a prime example, he assured readers that “some necessary balance … between exports and imports, or the like, will be brought about without deliberate control.” How sensible this must have seemed, midway through two decades in which U.S. exports and imports were indeed closely balanced. Why force all those economics students to suffer through Smith’s overly verbose asides about “preferring the support of domestic to that of foreign industry”?

The result is that the modern economist often plays the role of Wile E. Coyote, pressing confidently forward with plans that, unbeknownst to him, have no actual support. Except it is not his own well-being but that of countless American workers, families, and communities that risks a plunge into the canyon below. Still, the effect of forcing the economist to look down can be striking.

Press a proponent on why capitalism will deliver prosperity under globalization, and the account drifts gently off into the void. In the domestic economic context, so-called “supply-siders” have developed a theory whereby whatever policies are most beneficial to investors, who are presumed to be employers, will inevitably benefit workers as well. At least the myth that a “rising tide lifts all boats” can assume that the boats are all moored on the same side of the ocean. What is the story of how the Ohio worker benefits when the local investor moves his capital to Shenzhen in search of a higher return?

“The modern economist often plays the role of Wile E. Coyote, pressing confidently forward with plans that, unbeknownst to him, have no actual support. Except it is not his own well-being but that of countless American workers, families, and communities that risks a plunge into the canyon below.”

One approach might focus on the Chinese worker. Additional investment in Shenzhen boosts employment and wages there, and those workers will consume more American goods and services, boosting employment and wages here. But even stipulating that some Chinese consumer demand might eventually reach back to America, it will not match the demand spurred by a domestic enterprise. Smith and Ricardo never suggest that this pursuit of profit abroad will align with the public interest at home, no other theory gives a reason that it should, and empirically it has not.

A second approach might focus on the American investor. By maximizing his profit in Shenzhen, he will himself have more income, which he can then spend on a larger sofa in Ohio. Of course, the sofa itself will probably be made in Shenzhen as well, but perhaps the Ohio salesman can receive a larger commission. This story has not misapplied Smith, it has ignored him completely. The rationale for capitalism has never been that by maximizing the profits paid to investors, society will prosper. Its rationale is that in trying to maximize their profits under certain conditions, investors will behave in ways that do generate prosperity.

Smith saw high profits as inversely correlated with the public interest, warning that “the rate of profit does not, like rent and wages, rise with the prosperity, and fall with the declension, of the society. On the contrary, it is naturally low in rich, and high in poor countries, and it is always highest in the countries which are going fastest to ruin.” Unlike “the proprietors of land” and “those who live by wages,” he observed, the interest of “those who live by profit has not the same connexion with the general interest of the society.”

We can as easily tell this alternative story about our Ohio investor: He invests in Shenzhen instead of Ohio, reinvests his profits into other foreign operations or uses various legal mechanisms to avoid the taxation that would accompany a realization of his capital gains, and ultimately hands his money over to a hedge fund that speculates in options markets. He never consumes or invests a dime more in Ohio than he would have as owner of a local factory—though he may finance a foreign factory that bankrupts a local one. He signs the “Giving Pledge” and, dying a wealthy man, leaves enormous sums to reputable foundations that provide addiction treatment and housing assistance to the underemployed residents of his home city. He also leaves a tidy sum to a prominent think tank, endowing a chair in international capitalism, whose holder delivers an annual speech on the ways open markets help Americans economically.

Does this alternative story about our Ohio investor seem more or less likely than the one where he becomes an avid sofa connoisseur, boosting local employment for furniture salesmen? Economic theory cannot answer the question definitively. The political economist must make assumptions about the opportunities available and how someone would weigh the economic and social costs and benefits of each. Ricardo cited “the fancied or real insecurity of capital, when not under the immediate control of its owner,” but does that hold today, after decades in which guaranteeing the security of investments abroad has been an explicit policy goal? In his Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759), Smith argued that nature had endowed mankind “not only with a desire of being approved of, but with a desire of being what ought to be approved of; or of being what he himself approves of in other men.” Of what does the modern financier approve, after decades of enthusiasm for Milton Friedman’s declaration that “The Social Responsibility of Business Is to Increase Its Profits”?

What economic theory can tell us is that, insofar as the Ohio investor does reallocate his capital to Shenzhen, America is worse off than had he chosen the best option available in Ohio. That the investor might earn a lower return domestically is simply not of much concern to the people of his community, who would have a local employer offering well-paying jobs and supporting a broader ecosystem of suppliers and customers. Let all of them buy sofas.

At this juncture, many economists will attempt to conflate globalization’s corrosion with useful features of economic dynamism like automation and competition. With such skepticism of the “free” market, the argument goes, the people of Ohio would all still be living and working on farms. Not so.

The process innovations by which capitalists find ways to produce more output with less labor are the sine qua non of economic progress and a great force for good in the domestic economy. They differ from globalization’s substitution of foreign labor for domestic in two vital respects. First, they tend to occur gradually and to boost output more rapidly than they reduce labor. In the manufacturing sector, for instance, productivity growth from 1947 to 2000 averaged more than 3% annually—that is, producers halved the labor needed for the same level of output every 20 years or so. Yet manufacturing employment grew by millions. Only since 2000, when similar or slower productivity growth was accompanied by stagnant or declining output, has employment collapsed. Second, even when process innovation does reduce employment, the result is a still-healthy and typically growing local enterprise, offering higher-paying jobs for some that can in turn help to support other enterprises and employment in the community. That’s hardly comparable to shuttering a business, or failing to start one in the first place.

“What economic theory can tell us is that, insofar as the Ohio investor does reallocate his capital to Shenzhen, America is worse off than had he chosen the best option available in Ohio.”

Domestic competition moves employment opportunities to a new firm, or perhaps even a new location or occupation. But in this circumstance, declining labor demand in one place bears a hydraulic relationship to increasing labor demand in another. Typically, some firms in a given region will be winning while others are losing, which buffers the net impact on local economies. Long-term net flows of capital from one region to another will tend to occur on the same timescale as domestic migration. Areas with relatively looser labor markets become more attractive sites for subsequent investment. None of this holds true when regions separated by 7,000 miles of ocean, a century of economic development, and incompatible political systems find themselves in a common market.

The prosperity-creating cycle of creative destruction requires entrepreneurs working in parallel both to render labor less necessary in some places and find new uses for it in others. Only when capital must seek out the labor available—when conditions are such that, per Smith, each businessman “naturally inclines to employ his capital … to give revenue and employment to the greatest number of people of his own country”—can we expect this cycle to operate well and to the nation’s benefit. In recent years, it has not.

Bounding the Market

If we want capitalism to deliver broad-based, rising prosperity in America, then we must have a well-theorized understanding of the conditions under which it will succeed. A model focused on ensuring that wealthy people can earn the greatest possible return on their capital is not capitalism; it’s oligarchy, and its track record is quite poor. Capitalism works for capital, labor, and consumers when all are indispensable to each other’s goals and each gains from their achievement. Interdependence is what translates the pursuit of private profit into public benefit.

An indispensable element for maintaining this interdependence is the bounding of the market, so that the various economic actors have no alternative to each other. In a bounded market, economic analysis and legal treatment of activity depends on whether it occurs within the boundary, across it, or beyond it. That boundary might hypothetically take any form, but in practice it will be a physical boundary, typically a national one. By contrast, globalization and its underlying theory make the goal a boundless market, in which borders have as little relevance as possible to economic transactions.

A bounded market is not an isolated one; goods and services, capital, and people can enter and exit. But their flows are controlled, and for a well-functioning capitalist system the principle of control is balance. Through restrictions on trade or capital flows, public policy can force imports and exports into balance, so that goods and services are exchanged for each other rather than for financial instruments. Increased fulfillment of domestic demand via foreign labor (imports) would occur only alongside a parallel increase in foreign demand for domestic labor (exports). Inflows and outflows of capital would equalize as well. Balance imposes the necessary interdependence on labor and capital while also allowing for the actual benefits of trade that Smith and Ricardo described.

Choosing a free but bounded domestic market over globalization implies neither “central planning” nor a “closed economy.” A great benefit of defining clear boundaries for the market and then deferring to private-sector competition therein is that this strategy requires far less state intervention than with the enormous demands placed on bureaucracies to make globalization work. “Free trade” agreements are a case in point: Instead of negotiating endless treaties on “Investor-State Dispute Settlement” to ensure that the American government protects investors when they venture abroad, wouldn’t it be simpler just to tell those investors that they’ll be on their own?

“A great benefit of defining clear boundaries for the market and then deferring to private-sector competition therein is that this strategy requires far less state intervention than with the enormous demands placed on bureaucracies to make globalization work.”

Similarly, while limits on globalization’s cross-border flows are not the only constraints capitalism requires, they can reduce the need for other interventions. Competition policy, investment policy, labor policy, and financial regulation, for example, all play roles as well in creating the conditions in which the invisible hand leads the individual “to employ his capital in the manner in which it is likely to afford the greatest support to domestic industry, and to give revenue and employment to the greatest number of people of his own country.” Greater returns must not be available through the pursuit of monopoly rents or financial speculation. Incentives must exist to reward innovation and expansion that generates a high ratio of public to private returns. Workers must possess sufficient power in the labor market to advance their interests. Globalization makes all this much harder, while a bounded market lessens the need for government action on these fronts.

Even beyond the reach of the invisible hand, the bounded market advances the common good. Economic interdependence invariably strengthens the social fabric, as elites who might otherwise look outward for both peers and employees must instead look inward. Entrepreneurs would pay much greater attention to the quality of public education and the rigor of noncollege pathways—as economic imperatives, not subjects of charity—if the failure of those systems meant their own failure rather than an excuse to hire foreigners instead. Corporate executives in coastal cities might understand their fellow citizens in the domestic hinterland better if their supply chains traveled through it and thus so did they.

But where to draw the boundary? The coherent objection to insisting that American capital use American labor is that the “American” modifier is itself arbitrary. Why not draw the border around Ohio, or Cincinnati, or a particular neighborhood? Why not the Midwest, or North America, or, ultimately, the world? Many facets of that debate are beyond the scope of this discussion, but a few points bear noting.

First, nations matter, and operate as the basic political building blocks of our world. Globalization’s boosters prefer not to argue on these terms because doing so requires admitting that they do not think nations matter, or at least they do not want nations to matter. But devaluing the nation-state, weakening its sovereignty, and reducing a citizenry’s democratic control are inevitable consequences of constructing a global market. And notwithstanding liberalism’s one-world ideals, leaders in many other countries remain firmly committed to operating on behalf of their own national interests. If America pursues global supply chains while China pursues national ones, the result will be Chinese supply chains.

Second, a nation’s borders define a market with a common legal and economic regime. This limits variation in economic conditions and cost of living, cultural norms and expectations, and regulatory standards. Competition occurs and investment flows based on innovation and value, not arbitrage. With differences in degree rather than kind, shocks from sudden exposure to unprecedented circumstances are rare and change proceeds at a manageable pace.

“The national community is itself defined by the mutual dependence of citizens. Whether between labor and capital, rural and urban, civilian and soldier, members of a nation recognize that they owe something to each other that they do not owe to those outside the group. This is true not only as a moral matter, but also as a function of law and policy.”

Third, the national community is itself defined by the mutual dependence of citizens. Whether between labor and capital, rural and urban, civilian and soldier, members of a nation recognize that they owe something to each other that they do not owe to those outside the group. This is true not only as a moral matter, but also as a function of law and policy. Programs of social insurance, for instance, place a nation’s citizens in reliance on one another and their combined productive capacity. The national government takes on debts that burden the taxpaying public to make investments that benefit it. The political unity required to preserve a democratic republic relies upon recognition and reinforcement of these relationships, and the economic order should reflect it.

Fourth, markets tend toward convergence, so their borders should be drawn around areas within which convergence is desirable. Insofar as the nation recognizes itself as a community, it can support convergence that lifts up those least well off. Insofar as citizens face few linguistic, cultural, and legal barriers to internal migration—at least as compared to emigration—their potential mobility more closely matches that of capital and offers a release valve for economic pressure. Historically, America’s regional economies experienced strong regional convergence, stitching the nation more closely together.

In the era of globalization, convergence within America has stalled and even reversed, replaced by a convergence between the United States as a whole and the much poorer nations of the developing world. This is exactly what we should have expected, and indeed what many did expect and wish. Perhaps, from the perspective of a benevolent global dictator, this would be desirable. From the perspective of the American people, it is not.

“Globalization’s internal contradictions mean that, far from optimizing capitalism, it has left capitalists with a thorny dilemma: Free trade or a free market, choose one.”

The irony of the relentless push for globalization by the most passionate free-marketeers is that, in the process, they have grievously wounded the free market they prize above all else. The elimination of trade and capital barriers between China and the United States has imported not just cheap Chinese goods but also Chinese distortions and abuses. The investment decisions of American corporations now turn on the machinations of authoritarian communists. Every consumer shops in a market rife with forced labor. As Chinese policies warp investment decisions in ways harmful to the economic trajectory and national security of the United States, American policymakers must forfeit vital industries or respond with more heavy-handed interventions of their own. As the fortunes of a narrow set of “winners” diverge further from the broader base of “losers,” more redistribution is required to fulfill the empty promise of a larger economic pie.

Globalization’s internal contradictions mean that, far from optimizing capitalism, it has left capitalists with a thorny dilemma: Free trade or a free market, choose one. The correct choice is a free market in which domestic capital must make use of domestic labor to serve domestic consumers. Unlike globalization, that is a formula for broad-based prosperity.

The bounded free market is the economic model I thought I was defending in my confident case for free trade, because it is the model within which capitalism works and it is the model that economists teach. Unfortunately, it is not the model they have implemented. If they cannot defend globalization as it operates—and now would be rather late to start trying—then the time has come for them to find new work. Damage to their industry will be more than compensated for by advancements elsewhere.

Recommended Reading

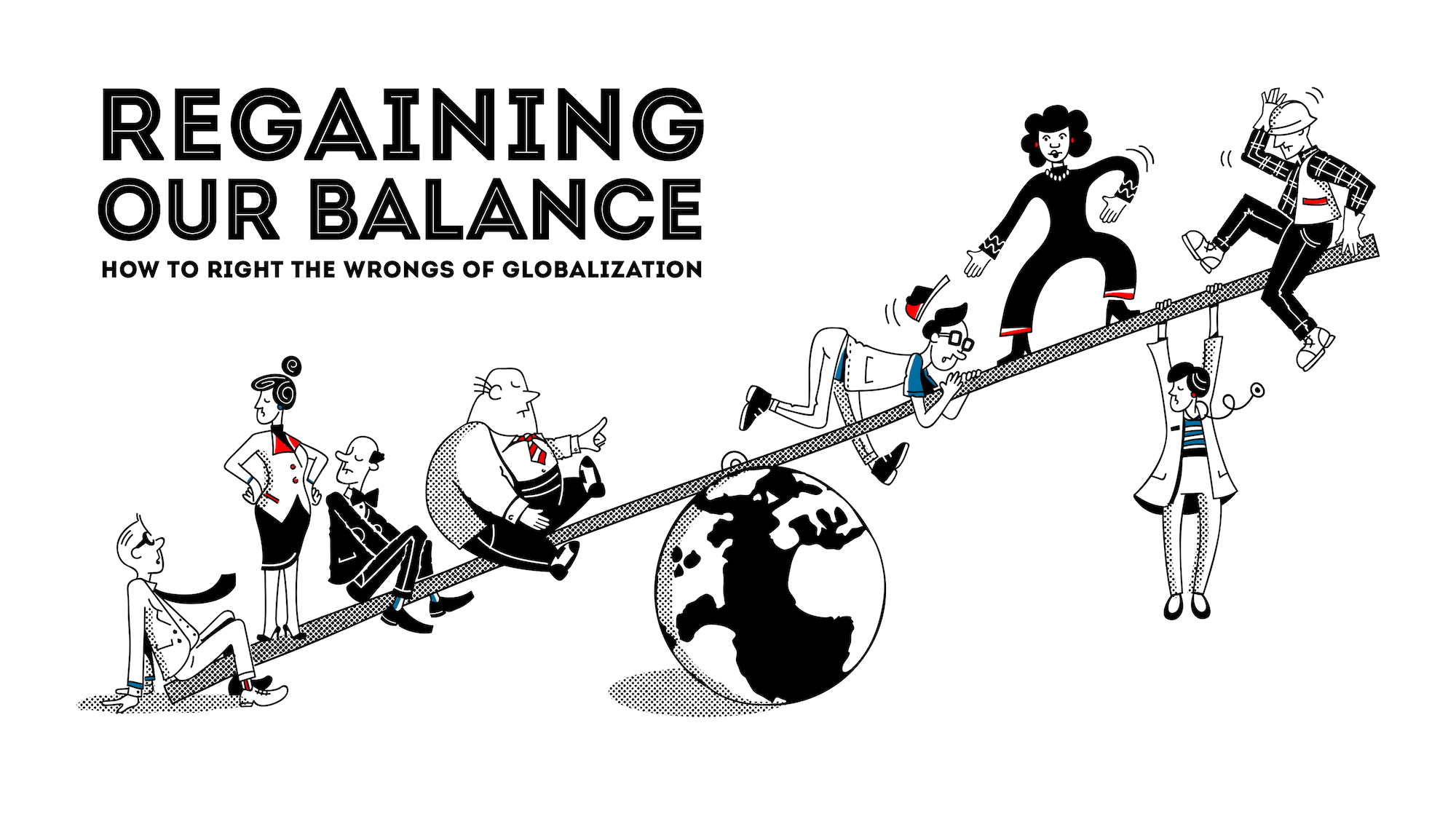

Regaining Our Balance

How to Right the Wrongs of Globalization

Has the Right Gotten It All Wrong?

Oren Cass joins David Bahnsen to discuss globalization, market orthodoxy, and much more.

The Conservative Confusion on Globalization

The question is not will we manage our economy’s interaction with the global market, but how, writes American Compass executive director Oren Cass.