How financialization erodes the American economy's foundations

RECOMMENDED READING

On a list of people who understand international investment, the president of the International Institute of Finance surely belongs near the top. So I was surprised to find myself, midway through a panel discussion last October, correcting the holder of that office on that very topic.

At issue was “Foreign Direct Investment” (FDI), which entails foreign residents holding ownership of American businesses. While commentators like to trumpet such “investment” as beneficial to the American economy, in fact it rarely is “investment” at all. “When we talk about foreign direct investment,” I explained, “about 98% of that is foreigners just buying American companies, not actually making tangible investments domestically. The same goes for most of what we call investment on Wall Street, which is just assets passing back and forth.” This did not sit well with my fellow panelist, who responded, “I actually think the majority of foreign direct investment in the US is actually greenfield investment, creating new jobs.”

So I looked it up. The Zoom era, for all its limitations, does ensure that speakers always have the Bureau of Economic Analysis at their fingertips. Thus, I could say when the conversation turned back to me, “I just pulled up the BEA press release because I want to make sure. Of $200 billion of foreign direct investment last year, only $4 billion of that was greenfield; virtually all of it was acquisitions. We see the same thing when we talk about investment generally, from Wall Street. Most of what we call investment today is the acquisition of an asset. When a private equity firm buys a company, it has not invested, it has traded a pile of money for a pile of equity.”1Press Release, “New Foreign Direct Investment in the United States, 2019,” U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, July 1, 2020.

This confusion over the nature of investment is pervasive among economic policymakers and commentators, has bled into the popular culture, and threatens the nation’s future prosperity. Actual-investment, by which I mean the allocation of capital toward the development of new productive capacity—the building of structures, the installment of machines, the creation of intellectual property—has been weakening in America for decades now. By contrast, what we often call investment, and what seems constantly to expand as a share of our economic activity, is merely the trading of assets for profit and power.

The distinguishing feature of non-investment is that it deploys no resources. Take the $100 million purchase of a rare painting. At first glance, this might appear a tragic waste of money. How many malaria nets could this dilettante have bought for the same price? But the outrage is misplaced; no resources have been consumed. One day, Party A has the painting and Party B has $100 million. The next day their positions have switched. Party A may go battle malaria with the $100 million just as surely as Party B could have.

The same phenomenon is at work when someone purchases $100 million in shares of Intel Corporation. First he had $100 million and someone else had the Intel shares; now the reverse is true. But no “investment in Intel” has occurred; indeed, for Intel, little has changed.2A publicly traded firm’s share price is not irrelevant to its operations, for instance higher-priced shares can provide the currency for stock-based acquisitions. And if the firm does need to tap public markets, demand at a high valuation will allow it to raise more capital. But trading of the shares amongst third parties does not itself provide resources or opportunities to the firm. It has no more resources at its disposal. It will build no new chip foundry as a result. When we call the exchanger of assets an “investor,” we imply that he has somehow contributed to the profit he realizes if Intel’s stock rises or it pays a generous dividend. But this is not true. He is a non-investor, cheering on Intel from the bleachers like a Dallas Cowboys fan who places a bet on his team in the big game.

Non-investors take three forms. One is the saver, who converts his cash into other assets that he expects will generate income and appreciate in value as the economy grows. Saving is an entirely sensible and responsible activity, but it does not represent actual-investment in the economy. Savers merely use various assets as vessels for their savings and grow richer as those assets increase in value, despite having done nothing to effect that increase. Indeed, the typical “investor” likely has no idea how to make an actual-investment and would struggle to find an opportunity to do so. Anyway, a financial advisor would likely counsel against it: far too much concentrated risk, putting so many eggs in one little firm’s basket, and all the worse if that firm is a local one.

Another non-investor, the speculator, is in the business of gambling on particular assets, attempting to outguess the market and thus generate a profit from buying low and selling high. This is what stock pickers do, as do many hedge funds. Thus, the Wall Street Journal properly headlined a report on Warren Buffett’s recent investments, “Berkshire Hathaway Bets Billions on Verizon and Chevron.”3Jenna Telesca, “Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway Bets Billions on Verizon and Chevron,” Wall Street Journal, February 16, 2021. This game is worse than zero-sum. For someone to be outperforming the market, someone else must by definition be underperforming it. But in the process, managers extract fees for placing the bets and other intermediaries take their own share for processing the transactions. For them there is no gamble at all, merely a guaranteed profit at someone else’s expense.

At least Buffett was buying the actual equity of real corporations. Increasingly, speculators like hedge funds prefer to speculate on mere derivatives that dispense with the fiction of any connection to the creation of wealth in the real economy, while (non-)investment banks specialize in creating such instruments for others to play with. The same day it reported on Buffett’s bet, the Journal also informed readers that an “Online-Trading Platform Will Let Investors Bet on Yes-or-No Questions.” The inspiration, according to the platform’s founder, came from working at Goldman Sachs, where he realized that much trading amounted to such betting anyway.4Alexander Osipovich, “Online-Trading Platform Will Let Investors Bet on Yes-or-No Questions,” Wall Street Journal, February 17, 2021. In some cases, bets ride on legal rather than economic outcomes, as when hedge funds finance lawsuits in return for a share of any proceeds or acquire distressed debt in hopes of outmaneuvering other parties in bankruptcy negotiations.5Benjamin Mullin & Corrie Driebusch, “Hedge Fund Elliott Management to Finance Lawsuit Against Streamer Quibi,” Wall Street Journal, May 4, 2020.

The third non-investor is the controller, who acquires an entire enterprise and takes responsibility for its operation but, rather than investing in and improving it, extracts available resources at the expense of its sustainability and those who rely on it. Private equity firms fit this description when they load companies with debt, collect dividends and fees, cut costs, outsource operations, and then resell what’s left—often to other private equity firms or even to themselves.6Julie Segal, “Private Equity Firms Used to Sell Half Their Companies to Their Competitors. Now They’re Selling Them Back to Themselves.” Institutional Investor, March 19, 2021. They are less non-investors than dis-investors, actively eroding the economy’s capital base and converting productive assets and organizations into cash.

Wall Street’s descent into an economic sideshow would be mostly amusing if not for the havoc it wreaks in the real economy on which the nation’s prosperity depends. As non-investors have overrun the banks and markets and taken control of corporations, actual-investment has slowed. The nation’s capital base is smaller by literally trillions of dollars as a result, representing untold enterprises never built, innovations never pursued, and workers never given opportunity. The companies that need to deploy actual-investment have lost the capacity and mandate to do so, and instead hand cash back to non-investors at the expense of their own health. The top business talent that once filled the entrepreneurial and managerial ranks has followed suit, relocating to Wall Street and dedicating itself to collecting the lucrative fees that non-investors command for their performance. The circus tent is propped up by the Federal Reserve, whose bankers seem to have decided that asset prices must always go up, and have the money-printing power to make it so.

The result should be unsurprising: Productivity growth stalled, down from 2.1% annually during 1980–2009 to 1.2% during 2010–19, and negative in the manufacturing sector for five of the past six years. Wages stagnated, lower for production and non-supervisory workers in 2019 than 50 years earlier.7“Average weekly earnings of production and nonsupervisory employees, 1982-84 dollars, total private, seasonally adjusted,” U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, accessed March 23, 2021. The trade balance collapsed, falling from equilibrium in the 1970s to below -3% of GDP in 1999 and staying there.8“Shares of Gross Domestic Product: Net Exports of Goods and Services,” U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, accessed March 23, 2021. A pattern of wealth accumulation emerged in which nearly all gains go to the already-wealthy who hold capital. From 1989 to 2019, the liquid financial assets of households in the bottom 50% of wealth rose by $172 billion (+39%) while the top 10% gained $29 trillion (+291%). Factor in consumer credit, and the gains for the top 10% remain virtually unchanged while the bottom 50% find themselves with $1.5 trillion less liquid net worth than 30 years ago.9“Distributional Financial Accounts,” Federal Reserve, last updated March 19, 2021. Data is for fourth quarter of each year and converted to real 2020$ with CPI. Liquid Financial Assets include checkable deposits and currency, time deposits and short-term investments, money market fund shares, debt securities, and corporate equities and mutual fund shares.

That wealth at the top, concentrated primarily in corporate equity, comes attached to a giant question mark: what are American businesses worth? One cannot eat, or even cruise the San Francisco Bay on, a stock certificate. The asset valuations that exist on paper today rely on an assumption that the nation’s corporations can and will employ the nation’s workforce in pursuit of increasing productivity and profitability in the decades to come. Recent evidence suggests otherwise, and the trajectory of investment suggests absolutely not. This does not mean “sell your stocks,” nor that the non-investors continuing to plow money into them are irrational. To the contrary: In accounting terms, they may well be worth every penny. What real-world prosperity those dollars will correspond to is another matter entirely.

Markets are not self-regulating, and these problems will not solve themselves. For capitalism to deliver on its promise, policymakers will have to do their jobs and re-establish the conditions in which it will function well.

Whither Investment?

The state of actual-investment is understood so poorly that experts cannot agree even on its general direction. For instance, a 2015 Aspen Institute report begins, “U.S. capital investment spending has faltered since the dot-com speculative bubble which burst in early 2000. It has not kept pace with the economic growth, profits, cash flows or virtually any other metric one could use to benchmark investment spending.”10Thomas J. Duesterberg & Donald A. Norman, “Why Is Capital Investment Consistently Weak in the 21st Century U.S. Economy?” Aspen Institute, April 2015. Or, as Senator Marco Rubio more succinctly opened a landmark 2019 report from the U.S. Senate’s Small Business Committee: “Business investment in the United States is decreasing.”11Sen. Marco Rubio, “American Investment in the 21st Century,” U.S. Small Business Committee Project for Strong Labor Markets and National Development, May 15, 2019.

Not so, argued prominent non-investor and former Obama administration official Steven Rattner in a 2018 New York Times op-ed: “Business investment has remained between 11% and 15% percent of gross domestic product since 1970. Last year, corporate investment, which includes structures, equipment and the like, totaled 12.6% of GDP.”12Steven Rattner, “The Myth of Corporate America’s Short-Term Thinking,” New York Times, July 2, 2018. Fellow non-investor Cliff Asness quoted this view approvingly at a 2020 event hosted by the American Enterprise Institute.13“Was Milton Friedman Right About Shareholder Capitalism?” American Enterprise Institute, October 6, 2020.

Technically, both sides are correct. Rattner and Asness point to “gross investment”—that is, the total amount spent in a given year—but fail to account for the “consumption of fixed capital” that occurs each year as prior years’ investment is used up. This is the equivalent of measuring snowfall without accounting for the rate of melt—it might be interesting to know how much has ever fallen, but what more likely matters is the accumulation. Aspen and Rubio, by contrast, focus on “net investment”—that is, the total addition to the economy’s capital stock after accounting for both the addition of new investments and the depreciation of old ones. Net non-residential fixed investment as a share of GDP has fallen by almost half, from 4.1% in the 1970s and 80s to 2.5% in the 2010s.

The divergence between gross and net investment is a result of its changing composition. The classic categories of investment, structures and equipment, account for 87% of the nation’s capital base and the rate of investment there has been declining in both gross and net terms. The declines are offset in the economic data by rising investment in intellectual property (IP).14“National Income and Product Accounts,” U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, table 5.10, accessed March 23, 2021. But IP is not like other forms of investment—its value is more speculative and erodes more quickly. Indeed, official U.S. economic data have classified spending on IP as investment for less than a decade.15Carol E. Moylan & Sumiye Okubo, “The Evolving Treatment of R&D in the U.S. National Economic Accounts,” U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, March 2020. Not by coincidence does Rattner leave it unmentioned when making his case that investment has held steady, listing instead the categories for which this is certainly not true.

A concrete microcosm of the nation’s investment shift is a firm that doubles down on design capabilities while offshoring its manufacturing. As long-time Intel CEO Andy Grove observed, such a strategy threatens not just the nation’s industrial base but its long-term capacity to innovate.16Andy Grove, “How America Can Create Jobs,” Bloomberg Businessweek, July 1, 2010. Further, an economy shifting toward heavier reliance on short-lived capital will need to reinvest more rapidly just to stay in place. America has not been up to that challenge.

With declining investment in structures and equipment and rising IP investment unable to make up the difference, the base of invested capital atop which the American economy operates has weakened. From 2009 to 2017, the nation needed $22.9 trillion in gross investment to match the average growth rate of the capital stock during 1970–99 (3.8% of GDP annually). Instead, investment totaled only $19.6 trillion. After consumption of fixed capital, net investment was $2.5 trillion lower, leaving American firms and workers 10% less capital to work with.17To model the level of gross capital investment required to achieve the benchmark level of net capital investment, I assume that changes to the capital stock in each year other than gross investment—consumption of fixed capital, stock reconciliation adjustments, etc.—remain constant as a percentage of the capital stock at the year’s start. “National Income and Product Accounts,” U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, table 5.10, accessed March 23, 2021.

The problem is most obvious in specific industries, like manufacturing, that have suffered the greatest shortfall. During 1970–99, net investment in manufacturing averaged 3.6% of manufacturing sector value-add. Then, just as China was joining the World Trade Organization in 2001 and America’s trade deficit exploded, manufacturing investment collapsed. Net investment as a share of value-add averaged 4.3% during 1998–2000 and then 0.5% during 2002–04. During 2000–17, the average was 2.2%, leading to a $1.0 trillion shortfall over the period, relative to the 1970–99 rate.18“Fixed Asset Account Tables,” U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, tables 4.1, 4.4, 4.7, accessed March 23, 2021; “GDP by Industry – Value Added by Industry,” U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, accessed March 23, 2021.

Policymakers devising the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 hoped that the promise of lower tax rates and thus higher profits would induce rising investment. This did not happen. Rather, investment slowed after the Act’s passage, and most economists have struggled to identify an initial effect.19Symposium, “Trump’s Tax Reform Happened, Now What?” American Enterprise Institute, Fall 2019. “The theory tells us that we should be looking at business investment,” explained the American Enterprise Institute’s Alan Viard in late 2019. “So far, a sharp uptick in investment has not occurred.”20Alan D. Viard, “The Misdirected Debate About the Corporate Tax Cut,” American Enterprise Institute, October 11, 2019.

The Softening of the Firm

Responsibility for domestic investment lies ultimately in the non-financial business sector, which the capitalist system relies on to deploy the nation’s resources productively.21See Rubio, American Investment, quoting Adam Smith, Heiner Flassbeck, Paul Steinhardt, and Alan Viard. The assumption that this will happen undergirds much of neoclassical economics and, especially, the obsession in right-of-center supply-side economics with cutting taxes—lower tax rates should mean more capital available for businesses to invest and the prospect of greater profits should strengthen the incentive for them to do so.

Financial firms and markets play a vital role in this process, moving capital to those who need it and can use it most productively. Operating companies pay for access to that capital, both delivering a return to those who provide it and a fee to those who facilitate its transfer. But typically, an operating company’s use of such services would be limited to its start-up, when it must invest before it is profitable, and to situations where an infusion of capital is needed to finance a major new initiative or overcome a crisis.22Firms also maintain ongoing commercial banking relationships to manage cash reserves, fund working capital, etc. A sustainably profitable firm is, by definition, generating sufficient cash from operations to (1) fund the investment necessary to maintain or grow its capital stock, and (2) return a profit to the shareholders who are the owners of the capital that the business uses.

That was historically the case, and many assume that it remains true. “Profits are what keep a business going and allow it to thrive,” says former UN Ambassador Nikki Haley. “They generate the funds needed for more job creation. You don’t need an advanced economics degree to understand this.”23Amb. Nikki Haley, “Capitalism Wins,” PragerU, February 8, 2021. But that’s not how the economy works today. “Since the 1980s, in aggregate, corporations have funded the stock market rather than vice versa (as is conventionally assumed),” explains economist William Lazonick. “Over the decade 2005–14 net equity issues of nonfinancial corporations averaged minus $399 billion per year.”24William Lazonick, “Stock Buybacks: From Retain-and-Reinvest to Downside-and-Distribute,” Brookings Institution, April 2015. Whereas corporations used to retain and reinvest roughly half of their earnings, Senator Rubio’s report notes, that share has fallen below 10%, with the rest paid out to shareholders. From 2008 to 2017, corporations paid out 100% of their earnings.25Rubio, American Investment.

This change in our system of capitalism is more starkly apparent at the firm level. Take firms headquartered in the United States and traded publicly on the New York Stock Exchange or the NASDAQ, and place them into three buckets:

- First are the Sustainers, which fit our standard model for a successful company. Sustainers are profitable, and that profit is sufficient both to make investments that grow their capital bases and to return money to shareholders. Put another way, they can and do invest in new assets faster than they use up existing ones. Most companies in a well-functioning capitalist economy should be Sustainers and, historically, most were.

- Second are the Growers, which fit our standard model for a company that requires access to capital from financial markets. Growers are investing to expand their capital base, and investing more than they can finance through their own profits. They tap the financial markets to make up the difference by issuing equity or debt, generating investable cash.

- Third are the Eroders, which do not comport with our intuition. Eroders have enough profit to grow their capital bases like Sustainers and still return cash to shareholders, but they choose not to. Instead, they actively disinvest from themselves, allowing their capital bases to erode even while paying to shareholders the resources they would have needed if they wanted to maintain their health.

Not all companies fit these profiles, but the vast majority do—90% of market capitalization fell into one of these three categories during 1971–2017. (For a detailed discussion of the creation and analysis of these categories, see the research brief accompanying this essay, The Corporate Erosion of Capitalism: A Firm-Level Analysis of Declining Business Investment, 1971–2017.)

A healthy market economy should have a meaningful set of Growers and the vast majority of firms operating as Sustainers. A small group would be Eroders, either for miscellaneous one-time reasons or because their businesses were no longer viable and returning cash to shareholders while winding them down was the best course of action. This was indeed the picture in the past. From 1971 to 1985, Sustainers accounted for 82% of market capitalization on average, Growers for 9%, and Eroders for 6%. During this period, these publicly traded companies tapped financial markets for 3.1% of GDP by issuing stock and debt, and returned 4.6% of GDP to financial markets in the form of dividends, stock buybacks, interest, and debt repayment, producing a net outflow from the real economy equal to 1.5% of GDP.

Then, as described in aggregate terms by Lazonick and Rubio, firms changed their behavior. In the 1990s, Eroders accounted for 16% of market capitalization; in the 2000s, 34%; in the 2010s, 42%. In 2017, Eroders accounted for 49% of market capitalization while Sustainers accounted for 40%. The prevalence of Growers had fallen to 3%. The net outflow of cash from the real economy had more than doubled as a share of GDP, to 3.5%.

These trends progressed steadily over time but saw a particular inflection point around the year 2000. For manufacturers, the Eroder share of market capitalization climbed from an average of 16% during 1998–2000 to 45% during 2003–05. In the information sector, which includes media, communications, internet, and software companies, the Grower share fell from an average of 14% during 1998–2000 to less than 1% during 2003–05, while the Eroder share rose from 20% to 60%.

The information sector’s trajectory is also notable for its unique starting point, with more than 30% of market capitalization associated with Growers during 1971–72. AT&T accounts for most of this market capitalization. In the early 1970s, it was still making annual capital expenditures larger than its total earnings before income, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA), while raising new funds through the sale of stock. Its decline from a Grower to a Sustainer to an Eroder by the mid-1980s is in some sense the story of the nation’s economic transition.

AT&T’s trajectory is somewhat confounded by its break-up in the mid-1980s, but the same pattern appears at IBM. During the 1970s, IBM consistently sent just 30 cents to investors for every dollar of capital expenditure. That figure rose steadily and then skyrocketed in 2004 as the firm transitioned from a perennial Sustainer to a permanent Eroder.

The shift toward a less asset-intensive “knowledge economy” might seem a plausible reason for the transition in firm behavior, but the benefit of a firm-level analysis is that each firm is evaluated relative to its own capital investment and consumption, not an arbitrary threshold. Thus, less asset-intensive firms could still themselves be Growers and Sustainers, albeit at lower investment levels. Instead, the typical firm profile has transitioned from Sustainer to Eroder regardless of business model.

Indeed, the massive technology firms with the largest market capitalization—Apple, Alphabet, Microsoft, Amazon, and Facebook—all had sufficient capital expenditures to qualify as Sustainers in 2017 (though Amazon falls into none of the categories because it returned no cash to shareholders26Indeed, Amazon is notable for its insistence on emphasizing long-term investment over cash payments to shareholders. Lauren Feiner, “Amazon Told Investors They ‘May Want to Take a Seat,’ Here’s What That Means,” CNBC, May 1, 2020.). The economy’s transformation is playing out economy-wide, at firms such as Johnson & Johnson, Exxon Mobil, Wal-Mart, AT&T, Pfizer, and Cisco. Whereas 1 of the 60 largest firms in 1977 was an Eroder, and 9 of the 60 largest in 1997, 37 of 60 were Eroders in 2017.

Cisco is an especially striking example, having flipped from Sustainer to Eroder in 2003 and remained there ever since. While policymakers rightly excoriate China’s mercantilist efforts to boost Huawei as a national champion, a fair share of blame must also go to the U.S. leader that has executed $101 billion in share buybacks over the past 15 years while making only $15 billion in capital expenditures. Bear in mind how destructive the Eroder model is. What was once an outlier is now the norm, with firms not just underinvesting in but actively divesting from themselves.

The standard defense of firms returning so much capital rather than investing it is that this allows the resources to reach their best use. If managers believe they can “maximize shareholder value” by disgorging cash, they should do so. The recipients, in pursuit of higher returns, will then invest it elsewhere. “The investor either buys some other stock or invests in some other business that actually needs the money,” explained Kevin Hassett, chairman of President Trump’s Council of Economic Advisers. “The money is reinvested and is increasing the efficiency of the economy by moving cash to the firms that need it the most.”27Thomas Heath, “A Year After Their Tax Cuts, How Have Corporations Spent the Windfall?” Washington Post, December 14, 2018.

This fails in both principle and practice. As American Affairs editor Julius Krein has observed, if $1 trillion in annual buybacks indicates that “there are in fact no better investments to be made, and the corporate sector simply has no use for this vast sum,” then this “calls into question the viability of the free market capitalist system itself. After all, the entire social justification of free enterprise is that the private sector is the most capable of finding productive investments and deploying capital effectively.”28Julius Krein, “Share Buybacks and the Contradictions of ‘Shareholder Capitalism,’” American Affairs, December 13, 2018. It is a dereliction of duty for the managers of a profitable firm to claim they have no productive uses for their profits and so must hand them over for someone else to invest, especially when they do so as their own firm loses its competitive advantage or consumes its capital stock.

The maneuver also initiates a sordid game of hot potato—I don’t want to invest this; here, you do it. In Hassett’s imagination, the shareholders to whom the profits return are themselves investors who can deploy the capital productively. That’s not reality. When a public company hands back capital to the financial markets, it throws the resources over an invisible wall, from the land of investors who might deploy it productively to the land of non-investors who are unlikely to do so. The non-investor may choose to convert the capital into personal investment or consumption, buying that bigger boat, say, or else turn around and non-invest in some other asset. Perhaps with the cash they receive when Intel buys back its own shares, they purchase shares of Boeing. But they have not invested in Boeing, merely given the cash to someone else who once held the shares. I don’t want to invest this; here, you do it.

How and when does the capital thrown from the productive economy into the financial markets and the hands of non-investors ever make its way back to productive use, especially in a world where the cash flowing out of Eroders exceeds by a factor of 12 the cash flowing into Growers? Generally speaking, it doesn’t. This is apparent both from the top-down view of macroeconomic data, which shows the long-running investment declines, and from the bottom-up view of firm-level data, which shows the outflow of cash from the operating economy to financial markets overwhelming the inflow of actual-investment. The mystery, then, is: Where does the capital go? The best answer would appear to be: Treasury bonds.

As we have seen, the cumulative gross investment shortfall during 2009–17 as compared to 1970–99 amounted to $3.4 trillion. Similarly, the excess outflow of cash from publicly-traded companies in the real economy (4.0% of GDP during 2009–17 versus 1.8% during 1971–99) amounted to $3.1 trillion. Over that same period, private domestic holdings of U.S. Treasury debt by individuals, mutual funds, banking institutions, insurance companies, and pension funds rose by $3.5 trillion.29“U.S. Treasury Statistics – Holders,” Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association, accessed March 23, 2021.

The game of hot potato proceeds until the cash reaches people who do not find attractive any of the non-investment opportunities available, at which point they lend it to the federal government directly or via low-yield savings instruments. If the federal government were issuing bonds to finance important long-term investments in infrastructure, basic research, and so forth, this might still be a happy ending. We are not so lucky. Instead the resources are used to shore up underfunded entitlement programs. The net effect is fewer people developing innovative new products and services and creating the enterprises, facilities, and equipment to provide them.

From Building to Buying

Our story thus far has focused on the managers of operating companies who fail to reinvest their profits or embark upon projects that require new investment. That story is incomplete, and in some respects unfair. After all, at least the corporate managers are in the corporate sector, trying to run real businesses. At least they could invest.

The root cause of the economy’s affliction is better located among the many talented business leaders who might once have joined or built businesses and deployed investment, but today choose instead to become non-investors. In the Harvard Business School’s Class of 2020, 34% of graduates entered finance and another 24% entered consulting. By comparison, 4% entered manufacturing and 3% entered consumer products.30“Recruiting – Data & Statistics, Class of 2020” Harvard Business School, accessed March 23, 2021. Whereas financial sector wages were comparable to those of other industries in 1980, by 2006 they were 70% higher. At the profession’s highest levels the gap was far larger: graduates of Stanford’s MBA program earned three times more in finance than in other industries during the 1990s.31Robin Greenwood & David Scharfstein, “The Growth of Finance,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, vol. 27, no. 2, Spring 2013.

In conjunction, the financial sector exploded in size and changed in character. Value-add attributed to banking and trading rose from 2.5% of GDP in 1970 to 4.8% in 2017, driven by the emergence of a category called “securities, commodity contracts, and investments” that rose from 0.2% of GDP to 1.6%.32“GDP by Industry – Value added by Industry as a Percentage of Gross Domestic Product,” U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, accessed March 23, 2021. Whether the “value-add” of all those securities, commodities contracts, and investments added value is another matter. In parallel with financial activities claiming an additional 2.3 percentage points of GDP, net investment was falling by 1.7 percentage points. Capital was becoming no more affordable to firms, and they were choosing to use less of it.

The damage from overdevelopment of the financial sector is two-fold, both depriving the real economy of much needed enterprise-building talent and then using that talent instead to manipulate and cannibalize what enterprises are built. The hedge-fund industry is the most obvious manifestation of this problem. Many just speculate in the secondary market, using shares of stock like poker chips. The “activists,” who amass sizable holdings in specific companies, typically do so with the intention of forcing the target to disassemble itself and disgorge more money to shareholders faster.

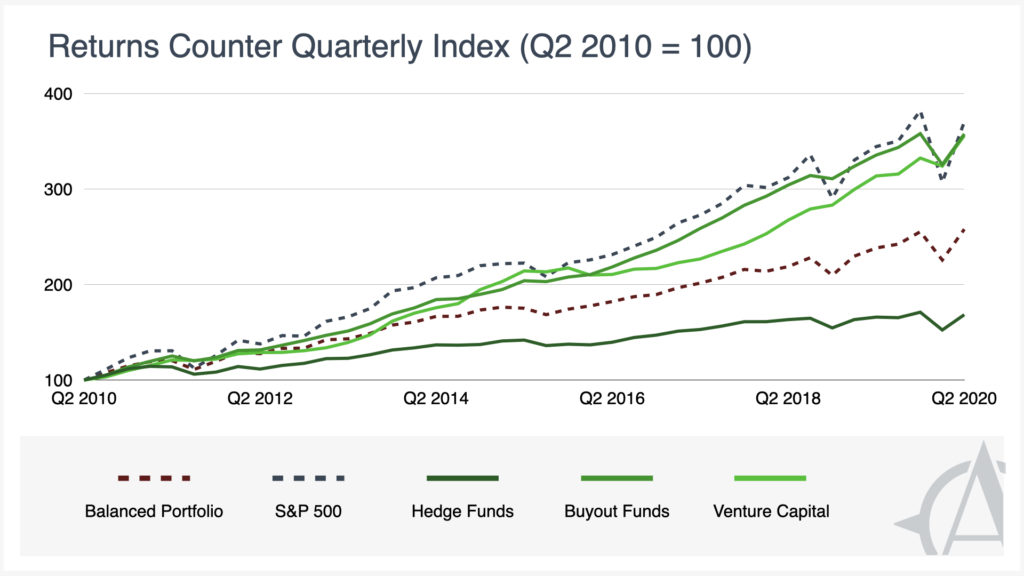

What’s most remarkable about the hedge fund managers is that they no longer succeed even on their own terms. As the American Compass Returns Counter documents, hedge funds in recent years have consistently and badly lagged the performance of both a simple S&P 500 Index Fund and a balanced portfolio of stocks and bonds that a more risk-averse saver might adopt. The typical hedge fund delivered a 70% return over the past decade, as compared to a balanced portfolio’s 160% return and the S&P 500’s 270% return.33“The Returns Counter,” American Compass, accessed March 23, 2021. The volatility induced by the pandemic’s onset in March 2020 should have been the industry’s moment to shine, but funds still managed to lose 11% in the first quarter and then draw just back to even in the second, leaving those who entrusted hedge funds with their savings barely ahead of the index fund and once again trailing a simple mix of 60% stocks and 40% bonds.34Wells King, “Coin-Flip Capitalism: Update (Q2 2021),” American Compass, March 22, 2021. Hedge fund managers collect their fees regardless.

Private equity firms take full ownership of the companies they purchase, offering the potential for actual-investment, but the strategy tends to be financial manipulation. “As an industry,” explains private equity veteran Dan Rasmussen in American Affairs, “PE firms take control of businesses to increase debt and redirect spending from capital expenditures and other forms of investment toward paying down that debt. As a result, or in tandem, the growth of the business slows.”35Daniel Rasmussen, “Private Equity: Overvalued and Overrated?” American Affairs, Spring 2018. By using debt to acquire a company and then using its profits to retire that debt, a private equity firm can earn a handsome return even if the company’s economic value declines. Being acquired by a private equity firm makes a company ten times more likely to go bankrupt.36Alicia McElhaney, “LBOs Make (More) Companies Go Bankrupt, Research Shows,” Institutional Investor, July 26, 2019.

As with hedge fund speculation, this strategy is no longer generating strong returns (though, again, the fees it generates to the managers are quite strong). Study37Ludovic Phalippou, “An Inconvenient Fact: Private Equity Returns & The Billionaire Factory,” University of Oxford, Working Paper, June 10, 2020. after study38Jean-Francois L’Her et al., “A Bottom-Up Approach to the Risk-Adjusted Performance of the Buyout Fund Market,” Financial Analysts Journal, July-August 2016. now finds that private equity performs similarly to a simple index fund, yielding “negative average risk-adjusted profits,” according to one new working paper from professors at the NYU and Columbia business schools.39Arpit Gupta & Stijn Van Nieuwerburgh, “Valuing Private Equity Strip by Strip,” National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 26514, November 2019. The Returns Counter likewise finds the industry battling a simple, low-cost index fund to a draw. The “wealth transfer” of $230 billion in management fees over the past decade “from several hundred million pension scheme members to a few thousand people working in private equity might be one of the largest in the history of modern finance,” Oxford University professor Ludovic Phallipou told the Financial Times.40Chris Flood, “Private Equity Barons Grow Rich on $230bn of Performance Fees,” Financial Times, June 14, 2020.

The exception that proves the rule is venture capital, which does make actual-investments in growing firms that need it. But it accounts for less than 20% of private-equity deal volume and concentrates heavily in a narrow segment of the economy: 77% of 2019 venture-capital investment went to software and the life sciences; 85% went to the West Coast and the Northeast.41“Venture Monitor,” PitchBook/NVCA, Q1 2020; “US PE Breakdown,” Pitchbook, 2020. One must scroll down more than 20 entries in a list of the largest venture capital exits in recent years to find one that is not an internet company.42Includes exits from 2009 to 2018. “The Unicorn Exits Tracker,” CBInsights, accessed March 23, 2021. It was a biotech company called Stemcentrx that was acquired for $6 billion in 2016 and imploded three years later.43Derek Lowe, “The Last of Stemcentrx,” Science (In the Pipeline blog), August 30, 2019.

The venture capital model relies on placing long-odds bets on start-ups whose business models can scale very quickly with as few assets as possible. The goal is to back the next Facebook or Google that hits the jackpot, compensating for the vast sums lost on the majority of companies that go nowhere. The approach disqualifies most businesses and industries from attention and precludes the slow, steady accumulation of productive assets that supports a thriving economy over time.

A surprising number of analysts survey the desolate landscape for American investment and ask, “What’s the problem?” Stock markets continue closing at new highs, after all, indicating that these supposedly “eroding” companies have never been more valuable. If capitalists were in fact engaged in systemically destructive behavior, this thinking goes, their strategies wouldn’t pay, and they would stop.

But strategies that will not pay for the nation’s prosperity in the long run can still pay their practitioners quite handsomely upfront. Especially after decades in which the economy amassed extraordinary stockpiles of valuable assets, the party can go on for quite some time before the keg runs dry. Signs indicate that reckoning may be approaching. Corporate profits from domestic industries fell for four straight years, from 2014 to 2018, even as the stock market was surging. The level in 2018–19 was 11% lower than at the prior business cycle’s peak in 2005–06.44Adjusted for inflation with BEA’s GDP Deflator. “National Income and Product Accounts,” U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, table 6.17A–D, accessed March 23, 2021.

Private equity firms, which rely on someone else to build valuable businesses that they can then load with debt and squeeze for profits, are running out of targets. They are raising non-investment capital much faster than they can use it, and as more such funds chase a dwindling set of potential deals, the valuations are rising, making it that much harder to deliver an above-market return, which of course they are not. As Bain & Company observed dryly in its Global Private Equity Report 2020, “Looking ahead, fund managers will continue to face a broad challenge: how to put record amounts of dry powder to work productively amid stiff competition for assets and worsening macro conditions.”45“Global Private Equity Report 2020,” Bain & Company.

The S&P 500 has thus far managed to defy gravity, but already its returns are unprecedentedly concentrated in a narrow set of massive technology companies.46Yun Li, “The Five Biggest Stocks Are Dwarfing the Rest of the Stock Market at an ‘Unprecedented’ Level,” CNBC, January 13, 2020. The nation’s industrial crown jewels, like Intel and Boeing, have suffered engineering meltdowns and are falling behind foreign competitors who invest like it’s their job, which it is.47Dominic Gates, “Boeing’s 737 MAX Crisis Leaves It Badly Behind in ‘Arms Race’ for Next Decade’s Jets,” Seattle Times, December 29, 2019. Ian King, “Intel Tumbles After New CEO Recommits to Chip Manufacturing,” Bloomberg, January 21, 2021. The nation’s savers look at their brokerage accounts and trust that the dollar amounts listed represent real wealth that they can someday consume, but that will work only if a robust capital base is ready to produce. Pension administrators who have allowed their funds to become critically underfunded, in part by assuming they could sit passively and reap profits that are not materializing, now count on “alternative [non-]investments” to make up the difference with Herculean returns, but no one can deliver them. Reversing this trajectory will require actual-investment, and people prepared to make it.

The Investor Returns

To help our capitalist system regain its balance, public policy will need to reform market rules in ways that both push entrepreneurial energy away from the destructive allure of non-investment in the financial sector and pull it toward the necessary actual-investment in the real economy. From one perspective, these objectives may appear at cross purposes. A vibrant financial sector, the thinking goes, creates deeper and more efficient capital markets that improve liquidity, distribute risk, and thus allow more capital to flow more cheaply to its best uses. Constrain the sector, and the cost of capital will rise, discouraging the very actual-investment we hope to encourage.

This is absurd. As the financial sector has become more muscular, actual-investment has fallen, not risen. Nor has access to capital corresponded to appetite for investment. J.P. Morgan estimates that the cost of capital for S&P 500 firms in 2013 was 8.5%, slightly higher than the historical median. Yet the median hurdle rate for a sample of these firms—that is, the expected return they would require before proceeding with a project—was 18%.48“Bridging the Gap Between Interest Rates and Investments,” J.P. Morgan, September 2014. It could be that businesses have become irrational. More likely, they feel incapable of investing effectively and pressure to return cash to shareholders instead. Either way, we can reject the idea that an unfettered financial market, generating massive profits for itself through non-investment, most effectively delivers plentiful capital to its best uses in the real economy.

Dispensing with the financial sector’s fictions is a good place to start. We should stop awarding the title of “investor” to people who don’t invest. The millions of Americans placing their savings into the market are savers. To be clear, saving is good and important. But savers still leave the investing to others. Those who make their money using those savings to buy and sell assets are traders. Those who try to turn a profit betting on the right assets are speculators. Those who buy firms and try then to engineer greater profits through financial maneuvers are manipulators. We will know an actual investor when we see one: he will be spending money in the real economy on labor and materials that expand an enterprise’s capacity and future potential.

We should measure more carefully the flow of resources between the real economy and the financial sector. For public companies, that information can be drawn from financial statements. But the Federal Reserve should provide comparable data for the economy as a whole: How much new capital flowed into firms through the issuance of debt and equity? How much flowed back to financial markets as dividends, stock buybacks, debt repayment, and interest? Chief financial officers should certify in their annual filings that their firms made sufficient capital expenditures in the past year at least to maintain their capital bases, or document the reasons they have chosen not to.

Once we understand that the financial sector’s glut of non-investment is not just failing to facilitate actual-investment but in fact preventing it, the case for a regulatory response becomes clear. Many economists and policymakers have urged a hands-off approach on the assumption that any interference would reduce capital’s availability and prevent it from reaching its best uses, but if the sector’s behavior is itself having those effects then public policy has a clear role to play in establishing guardrails within which the market can function well.

Policymakers should consider options such as:

- Imposing a financial transactions tax on asset exchanges in the secondary market;

- Raising tax rates on short-term capital gains and the proceeds from speculation;

- Prohibiting entities in the financial sector from behaving both as actual-investment banks that deploy resources in the real economy and non-investment firms that specialize in creating and trading assets amongst themselves;

- Making private equity firms liable for the debt that they load on the companies they acquire; and

- Mandating extensive disclosure from non-investment firms that hold assets for public pensions and non-profit endowments. Disclosures should include the details of all transactions, the flows of funds to and from operating companies in which they hold stakes, the calculations of returns, and the fees and profits distributed to managers.

We can also do much more to support actual-investment in the real economy. A good survey of policy options in this regard is available in American Compass’s recent symposium, Moving the Chains: 9 Strategies for Retaking Global Leadership in Industry and Innovation. These include industry partnerships for research and development, favorable tax treatment for investment, preferences for domestic production, a public investment bank, and more aggressive anti-trust enforcement.

Finally, policymakers will need to accept the disappointing reality that a nation’s resources are limited and borrowing or printing more money does not change this. If the government diverts resources from actual-investment toward itself but then fails to use those resources for public investment, the nation’s economic trajectory will suffer. Further, monetary policy can only have its desired effect if the market economy is operating as expected—with lower interest rates inducing actual-investment that boosts both demand and productivity. If extra money released into the economy merely inflates asset prices and then gets thrown right back at the government, a vital policy weapon is lost.

Without capital, capitalism is merely an ism—a belief set untethered from what is happening in the real economy. A well-functioning financial sector is vital to channeling capital toward its best uses, but so too is a public policy that sets the rules and constraints within which that sector operates. Such guardrails are not just consistent with capitalism, they are necessary to its success.

Recommended Reading

New Collection: Supply-Side Economics Beyond Tax Cuts

Long-term analysis shows the ineffectiveness of the Bush and Trump tax cuts

Sen. J.D. Vance on Financialization, Labor, and Rebuilding American Capitalism

Sen. J.D. Vance and Oren Cass discuss what has gone wrong with investment in the American economy and how conservatives should think about labor unions today.

How Wall Street Took Over Our Economy

Varun Hukeri features American Compass’s We’re Just Speculating Here research on financialization and falling U.S. investment.