Globalization is not the inevitable outcome of technological progress, nor is it a prerequisite to growth. The middle of the 20th century was considerably less “globalized” than the “first golden age” of globalization early in the century, was more technologically advanced, and delivered unprecedented levels of broad-based prosperity. Globalization done can also be undone. It is the result of policy choices, not immutable economic forces, as recent developments like the domestic investment surge in semiconductor capacity and Russia’s sudden expulsion from global trade and finance have demonstrated.

Just as policymakers chose the current order, they can choose to move beyond globalization toward more balanced global flows of goods, capital, and labor. They must consider how a balanced post-globalization market should look and what policies can achieve it.

Change will inevitably be gradual. Having spent decades digging its hole, America will need time to climb out, and filling in the pit will have costs. But upfront cost is no argument against making the investments needed to place the nation on a better economic trajectory. Who better to understand this principle than globalization’s advocates, practiced in proudly demonstrating their sophistication by explaining that shuttered factories, collapsing industries, and dying communities were for the best because the eventual results would benefit all?

Leaders across the political spectrum have taken encouraging steps in this direction, acknowledging the failure of the globalization experiment and pledging a new course. But that rhetoric is infrequently matched by action adequate to the scale of the problem. This is not for lack of options. Policymakers need to be judged not by what they are willing to say, but what they do.

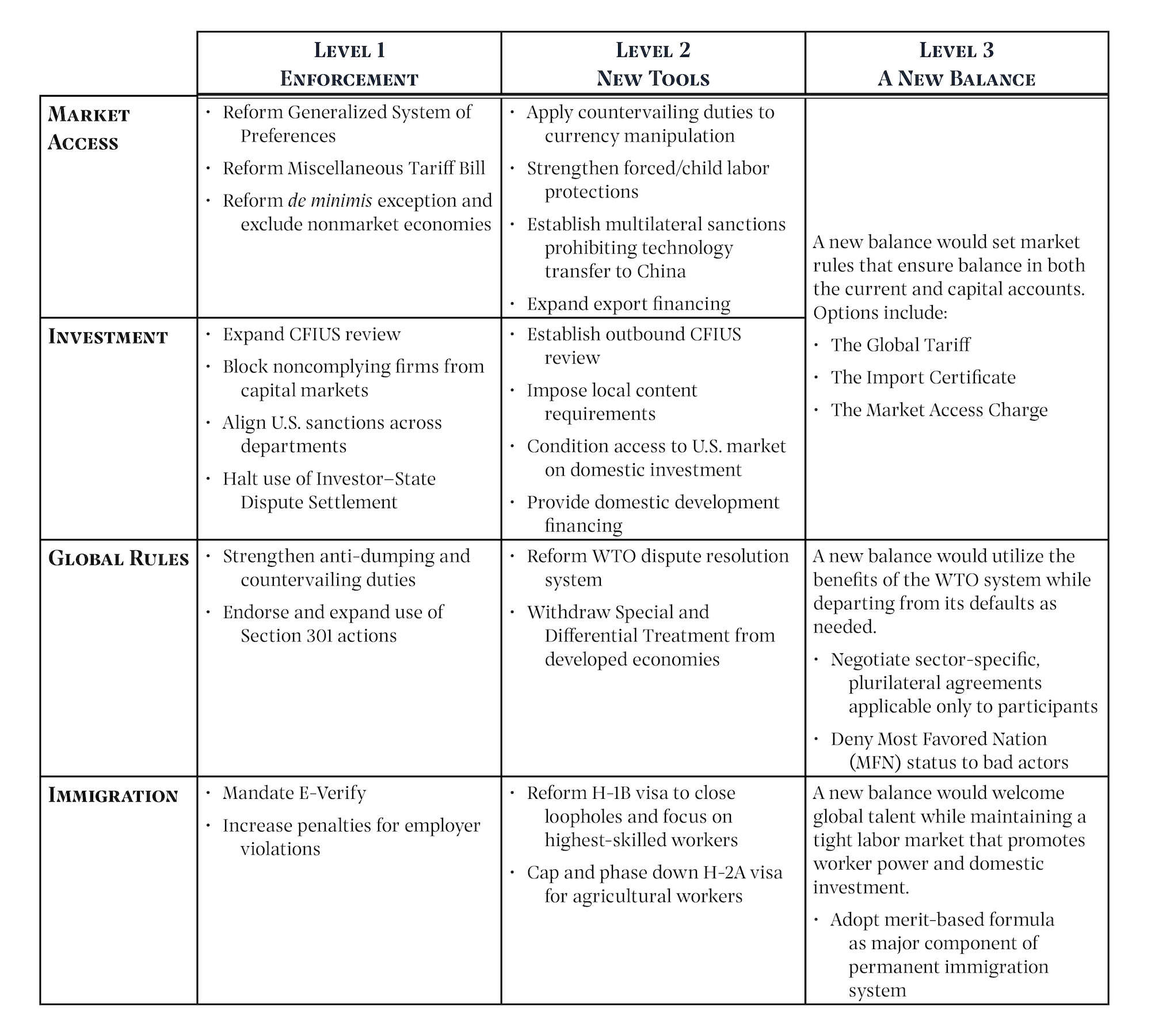

Righting globalization’s wrongs will require action on several fronts: market access and investment rules to govern the flow of goods and capital; sovereign actions taken in relation to global institutions; and immigration policy that affects labor market composition. In each case, policymakers who wish to take serious action, and to be taken seriously, must commit to using and enhancing existing tools of enforcement. Proceeding to the next level, the more aggressive step should be to create new tools that make globalization better serve American interests. The third level, and what should be the ultimate goal, is to articulate a vision beyond globalization that would allow the American economy to regain its balance.

This report provides an overview of the challenges in each area and examples of the policy options available on each front and at each level. Contrary to the once grand, now fatalistic claims that globalization is an inevitable and uncontrollable force, statesmen have the capacity to act, as well as the obligation.

The Balancing Act: An Overview

Policymakers can act on several fronts: market access and investment rules to govern the flow of goods and capital; sovereign actions taken in relation to global institutions; and immigration policy that affects labor market composition. In each case, policymakers who wish to take serious action, and to be taken seriously, must commit to using and enhancing existing tools of enforcement. Proceeding to the next level, the more aggressive step should be to create new tools that make globalization better serve American interests. The third level, and what should be the ultimate goal, is to articulate a vision beyond globalization that would allow the American economy to regain its balance.

Market Access & Investment

Globalization’s basic ambition is to establish a global market in which goods, services, and capital cross borders seamlessly, flowing from their most efficient providers to their most efficient uses. Widely differing economic conditions and national policies around the world have instead produced trade and capital flows that have weakened the American economy. The underlying problem is one of imbalance.

The flow of goods, services, and capital into and out of a national economy is recorded in the balance of payments—the summary of all transactions between one country and the rest of the world. Transactions fall into one of two accounts: The current account captures the flow of goods and services, with the net effect reflected as a trade balance that represent the nation’s net income. The capital account captures exchanges of financial instruments and assets, with the net effect reflected as a change in asset ownership.

These two accounts will always balance against each other. If one is in surplus, the other will be in deficit by the same amount, because any transaction must have comparable value on each side. If the United States imports more goods than its export income can pay for (i.e., if it runs a current account deficit), it must find some other way to pay—namely, by selling assets (i.e., by running a capital account surplus) and using the proceeds to buy imports. This is what the United States has been doing for decades.

Thus, the flipside of America’s stalled industrial output and accumulation of over $10 trillion in trade debt has been more than $10 trillion of capital account surpluses. Optimists describe this as “investment in the United States,” but almost none of it has taken the form of productive foreign investment in new domestic operations. Rather, the tangible effect has been the world acquiring American debt, equities, and real estate—instruments that represent claims on the nation’s future economic value. American investors, meanwhile, have not hesitated to move their own resources abroad—and even to China, boosting firms that pose direct threats to American interests and values. Each of these flows poses its own set of problems.

The Problem of the Trade Deficit

Reliance on cheap imports has reduced demand for domestic productive capacity. The resulting decline in investment and loss of productive capacity has weakened supply chains and transferred technical knowhow to other nations, offering competitors and adversaries an advantage while degrading the domestic industrial commons vital to innovation and growth. The loss has also eliminated millions of well-paying jobs and devastated communities and entire regions.

The Problem of Foreign “Investment”

Globalization has increased the flow of capital into the United States, but it has not increased investment. Instead, what is called “investment” is invariably the acquisition of existing assets, not the expansion of productive capacity through new “greenfield” capital. In 2020, foreign investors spent $120.7 billion to acquire, establish, or expand businesses in the United States. Less than 4% of that total went toward the establishment of new enterprises or expansion of existing ones. As of January 2022, foreign investors hold $7.7 trillion of U.S. Treasury securities. Their equity holdings have risen from 11% in 1980 to about 40%. They control over 35 million acres of agricultural land (greater than the acreage of Alabama or New York State). To sell U.S. assets like bonds, equity, or real estate is to sell future claims on American economic value. It presents serious economic vulnerabilities and is unsustainable. It can also grant controlling interests in key industries and insight into sensitive technologies and data; in 2016 and 2017, for instance, Chinese investors made 38 acquisitions of U.S. critical technologies, more than twice the total of any other country.

The Problem of Outbound Investment

While foreign acquisition of U.S. assets should concern policymakers, the outflow of American investors’ capital abroad should concern them no less. Context matters. An American corporation acquiring a foreign competitor with valuable technology is different from, say, the American financial sector channeling resources to a state-supported Chinese firm supplying the Chinese Communist Party’s surveillance apparatus, or Tesla moving the majority of its manufacturing capacity to Shanghai. These latter examples are neither hypothetical nor desirable.

Seeking Balance

The trade deficit and capital surplus appear in separate accounts, but they are conceptually intertwined and together tell a simple story: America has purchased imports with its assets instead of exports. Rather than produce things here and send them abroad in exchange for the goods produced abroad and consumed here, America takes in goods and sends back pieces of paper that represent claims on the nation’s economic future—all while reducing the nation’s future economic capacity and bolstering that of competitors. This is neither beneficial nor sustainable.

Policymakers should welcome international trade that generates prosperity for both sides, when the goods made in one nation are desired in the other, and vice versa. Such reciprocal trade is mutually beneficial, maintains balance between exports and imports, and thus maintains domestic industrial capacity. Likewise, foreign direct investment should be welcome when it expands the domestic productive capacity.

Level 1—Enforcement

Existing rules and enforcement tools already provide American policymakers with opportunities for improving economic outcomes.

Market Access

Under the Generalized System of Preferences, many imports from 119 developing countries and territories are allowed to enter the U.S. duty-free to promote economic development in those countries, regardless of whether they offer reciprocal treatment to American exporters. Yet in many cases, the result is less to promote development than to expose American producers to unfair competition from foreign firms exploiting weak labor and environmental standards. Congress should condition such preferential treatment on exporting nations adopting stronger standards that ensure American workers can compete on a level playing field. The Generalized System of Preferences and Miscellaneous Tariff Bill Modernization Act, introduced by House Ways and Means trade subcommittee chairman Earl Blumenauer (D-OR) and included in the House of Representatives’ America COMPETES Act trade title, is an example of legislation that would move the GSP’s eligibility criteria in the right direction.

Likewise, the Miscellaneous Tariff Bill (MTB) temporarily reduces or suspends import tariffs on certain goods, to ensure needed inputs can affordably enter the country. However, the MTB often benefits imports competing directly with American-made products, violating its intended purpose. Congress should restrict its application by limiting its benefits to only those intermediate inputs needed by domestic manufacturers (as proposed by the Coalition for a Prosperous America), or by prohibiting its application to finished goods that compete with domestic products, as the Generalized System of Preferences and Miscellaneous Tariff Bill Modernization Act would do.

Since the 1930s, U.S. law has allowed items of trivial value to enter the country duty-free, so that Customs and Border Patrol (CBP) need not assess every souvenir or small gift brought or mailed into the country. This de minimis rule, while sensible, no longer plays this common-sense purpose. In 2016, Congress raised the de minimis limit to $800, which now covers vast swathes of e-commerce, allowing $128 billion of duty-free imports to enter the United States in 2021, largely from China (in 2021, 63% of new sellers on Amazon in the U.S. were based in China). This trade not only violates the intent of U.S. law, but has also become an epicenter of consumer fraud and a leading vector for the importation of fentanyl and other harmful substances.

Reform here would be straightforward. In 1938, the de minimis limit was $1. Congress should return to a much lower limit and deny de minimis treatment altogether for nonmarket or hostile nations or frequent sources of fraud and illegal sales. Rep. Blumenauer’s Import Security and Fairness Act, also included in the America COMPETES Act trade title, would deprive de minimis treatment to goods from nonmarket economies or countries on the U.S. Trade Representative’s (USTR) priority watch list, and from goods subject to trade enforcement actions (e.g., Section 301 or Section 232 actions), though it would not reduce the overall limit.

Investment

The U.S. government established the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) in 1975 to scrutinize foreign investment transactions that might threaten national security. Since enactment of the Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act of 2018 (FIRRMA), non-controlling stakes in businesses involved with critical technology, critical infrastructure, or sensitive personal data, as well as some real estate transactions, also face review. This expanded scope still does not capture the full range of potential strategic concerns that foreign investment, especially from nonmarket or adversarial nations, can represent.

Congress should expand CFIUS’s scope to other critical industries including pharmaceuticals, agriculture, and media/entertainment. The bipartisan U.S. Pharmaceutical Supply Chain Review Act, introduced by Senators Marco Rubio (R-FL) and Elizabeth Warren (D-MA), would require CFIUS to examine foreign direct investment’s impact on the American pharmaceutical industry. Numerous senators have called on CFIUS to review specific agricultural transactions;the bipartisan Foreign Adversary Risk Management (FARM) Act would place the Secretary of Agriculture on CFIUS and expand the committee’s mandate to review foreign controlling stakes in American agriculture, as would several other bills; and Senator Warren has proposed banning foreign control of agricultural land, as several states already do. While CFIUS is already permitted to consider whether a transaction would impair U.S. industrial advantages, Congress could also expand review to encompass long-term national economic interest, as Senators Sherrod Brown (D-OH) and Chuck Grassley (R-IA) proposed doing through a new Commerce Department process in the United States Foreign Investment Review Act.

Outbound investment poses other challenges. Many Chinese firms, for instance, enjoy access to American financial markets and investment while avoiding American financial transparency standards. Their practices introduce excessive risk for American markets and investors, including retail investors and public pension funds. The bipartisan Holding Foreign Companies Accountable Act, enacted in 2020, sought to close this major loophole by prohibiting foreign companies from listing on U.S. exchanges if they fail to allow Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) inspection for three consecutive years. Congress should strengthen this provision, for example by further tightening the compliance window: the bipartisan Accelerating Holding Foreign Companies Accountable Act, which passed the Senate in 2021, would cut the window from three years to two. Such steps would also help address China’s abuse of Variable Interest Entities—shell corporations established by Chinese firms that allow Americans to invest in Chinese enterprises, but give those investors no real ownership rights or protections.

Of course, most Chinese firms are listed on Chinese exchanges beyond the reach of U.S. securities law. Major American asset managers nonetheless include these firms in their indexes, meaning that investments by both individual investors and pension funds holding index funds are flowing to companies not subject to American financial rules, many of which are already under U.S. sanctions for national security or human rights abuses. Congress should prohibit the inclusion of such companies in U.S. indices and associated index funds, as the Coalition for a Prosperous America has asked the Securities and Exchange Commission to do under existing authority.

U.S. sanctions laws suffer from many other gaps that prevent them from effectively blocking problematic investment flows. For instance, over 400 Chinese companies appear on the U.S. Department of Commerce Entity List, which designates firms subject to U.S. technology export controls, yet the vast majority of them can still receive American capital. Listed firms should be expelled from American capital markets, either by legislative action such as the American Financial Markets Integrity and Security Act proposed by Senator Marco Rubio (R-FL) and Rep. Mike Gallagher (R-WI), or by automatic cross-listing on the Treasury Department’s Non-SDN Chinese Military-Industrial Complex Companies List (NS-CMIC List). In its 2021 Annual Report to Congress, the independent U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission called on Congress to ensure that entities sanctioned under one U.S. authority are sanctioned in parallel under others.

Finally, American policymakers should rethink their approach to protecting U.S. investors abroad. The use of Investor–State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) mechanisms in trade agreements insulate investors from the risks of deploying their capital abroad, by removing disputes with foreign governments from the sovereign courts of those governments to non-state tribunals. While reducing investor risk, ISDS mechanisms also deprive foreign nations of sovereignty as a price of attracting investment and encourage American investors to move their capital to otherwise unattractive legal environments abroad.

One can appreciate why investors demand this treatment, but less clear is why providing it is in America’s national interest. Brazil has long refused to sign treaties that include ISDS, and has innovated with alternative state-to-state approaches; nations like South Africa, Indonesia, Ecuador have moved away from the use of ISDS; and ISDS skepticism in Europe is very high. The United States should also reject the use of ISDS. Similarly, American negotiators should permanently abandon discussions for a U.S.–China Bilateral Investment Treaty (BIT), which have been suspended since 2017. Investing in China should mean putting one’s capital at the mercy of the Chinese Communist Party. If investors are looking for a better legal environment, they could consider America.

Level 2—New Tools

Strengthening existing tools and deploying them more wisely can mitigate some of globalization’s harmful effects, but making globalization work for America will require much more. Policymakers need new tools to address conditions and policies elsewhere that yield unfavorable flows of goods and capital, and to foster conditions domestically that promote desirable flows.

Market Access

Foreign nations that manipulate their currencies artificially reduce prices for their exports and increase prices for imports from the United States. Policymakers should treat currency manipulation as the market distortion it is and subject it to the same countervailing duties imposed in other cases of unfair export subsidies. The bipartisan Leveling the Playing Field Act 2.0, introduced by Senators Rob Portman (R-OH) and Sherrod Brown (D-OH), is a good example of this approach.

Forced and child labor enable cheap production of goods not due to efficiency or “comparative advantage” but the violation of basic human rights. These violations and their economic effects introduce unfair import competition into the American market and violate deeply held values. U.S. law already prohibits the importation of goods produced with forced labor, but enforcement requires proof, which can be difficult to establish. Much stricter scrutiny of foreign supply chains is warranted. The bipartisan Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act, enacted in December 2021, created a rebuttable presumption that all goods manufactured in China’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region are the product of forced labor and may not enter the United States. Congress should more broadly shift the burden for the integrity and transparency of supply chains to the multinational corporations utilizing them, which bipartisan efforts like the Slave-Free Business Certification Act, introduced by Senators Josh Hawley (R-MO) and Kirsten Gillibrand (D-NY), would do. Congress should also create mechanisms for supply-chain transparency and institute a general prohibition on forced labor conditions for any future Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) or authorizations of Trade Promotion Authority (TPA).

While foreign firms can sell in America almost regardless of their practices, American firms often find themselves shut out of foreign markets. This problem is especially pronounced in China, which requires partnership with Chinese firms and transfer of technology as conditions of market access. In many cases, China outright steals American intellectual property. So long as China employs these practices, the United States should prohibit American firms from transferring technology into that nation, using mechanisms similar to the ones that prohibit the transfer of military and dual-use technologies to adversaries. The same standards used by CFIUS in prohibiting foreign acquisition of critical U.S. technologies could apply. Where American policy prohibits foreign control of a firm with sensitive technology, it should likewise prohibit transfer of that technology into China, where it will most likely be either legally or illegally appropriated.

American policymakers should seek a multilateral coalition of similarly aggrieved Western nations to impose these restrictions on technology transfer, strengthening their effect while also ensuring that no one nation’s firms lose out to another nation’s in the Chinese market. The multilateral Wassenaar Arrangement, in which 42 nations have agreed to place export controls on conventional arms and sensitive dual-use technology, provides a good template.

Finally, if the American market is to operate within a global one, American policy will need to support its domestic producers more effectively, just as other nations support theirs. One front in this competition is export financing. President Trump was correct to sign a reauthorization of the U.S. Export–Import Bank in 2019, and President Biden has proposed a domestic manufacturing initiative at the Bank to support American exporters in critical high-tech sectors like semiconductors and advanced batteries. Parallel efforts are needed for small exporters, like the 2019 U.S. Senate Committee on Small Business and Entrepreneurship plan to reauthorize the Small Business Administration, which would have modernized and strengthened the SBA’s export support programs.

Investment

The Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) already has authority to screen foreign investment in American companies and block transactions of concern. To curtail American capital flowing to foreign adversaries, Congress should establish a similar process to screen and block outbound investment. The bipartisan, bicameral National Critical Capabilities Defense Act would establish an interagency committee to screen outbound investment to adversary nations like China and Russia, preventing the offshoring of critical capabilities. The U.S.–China Economic and Security Review Commission has also endorsed this idea, recommending that “Congress consider legislation to create the authority to screen the offshoring of critical supply chains and production capabilities to the PRC [People’s Republic of China] to protect U.S. national and economic security interests…This would include screening related outbound investment by U.S. entities.”

Policymakers also need to address the decline in productive domestic investment, particularly in critical industries, by leveraging market forces. Local content requirements, which require that some percentage of a good’s value be made in the United States, provide one way to create guaranteed domestic demand while leaving competitors in the private sector to fill it. The Biden Administration has sought to strengthen federal procurement Buy America content requirements, as has the bipartisan Make It in America Act. But policy must go beyond federal procurement. Senator Josh Hawley (R-MO) and Rep. Claudia Tenney (R-NY) offer a good example of this approach in their Make It in America to Sell It in America Act, which would require that at least 50% of the value of certain goods critical to national security or the American industrial base be domestically produced for those goods to be sold commercially in the United States.

Rather than, or alongside, local content requirements, Congress could also require foreign firms seeking access to the U.S. market to build domestic capacity for serving that market. Quotas imposed by President Reagan on Japanese automakers, for instance, led them to move a significant share of their manufacturing for the U.S. market to the American South. The results speak for themselves: In 2021, Toyota overtook GM as the best-selling automaker in America and, as the company often touts, over 70% of the vehicles it sells in America are produced in its 14 North American plants (10 of which are in the United States). Toyota celebrated the 10 millionth Camry produced in Kentucky in 2021.

Finally, public investments and subsidies can make private investment in domestic productive capacity more attractive. For instance, the bipartisan CHIPS Act provides support for expansion of domestic semiconductor fabrication capacity. Likewise, a domestic development bank or finance authority could make greater financing available for private investment in manufacturing and industrial capacity. Good examples of this approach include the Industrial Finance Corporation Act introduced by Senator Chris Coons (D-DE) and the American Innovation and Manufacturing Act introduced by Senators Marco Rubio (R-FL) and Jim Risch (R-ID), which would provide patient capital to small manufacturers.

Level 3—A New Balance

The tools described at Levels 1 and 2 would help to address globalization’s many deficiencies. But they represent awkward patches to a fundamentally flawed system, and require complex interventions by policymakers in the American market. The underlying problem is that globalization encourages dramatically imbalanced flows of goods and capital, disrupting the conditions under which capitalism functions properly. Rather than construct contraptions to constantly bail out a leaky boat, policymakers’ long-term goal should be to patch the leak and impose basic constraints that restore balance to the domestic economy.

Balance does not mean isolation, which would have consequences as negative as globalization’s. Rather, the market’s “rules of the road” should ensure that goods and services imported are of equal value to those exported, which in turn would ensure a balance in capital flows. Trade could still occur at high levels, and certainly would occur in those places where other nations had substantial comparative advantages relative to America’s own. An added advantage would be that, to the extent balance is achieved, fewer government interventions in the domestic free market would be required. At least three approaches to imposing balance deserve consideration.

The Global Tariff

Rather than impose case-by-case, industry-specific tariffs to address particular disputes or seek leverage over other nations in negotiations, the United States could impose a simple global tariff on all imports that increases steadily in response to trade deficits and decreases in response to trade surpluses. Former U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer has suggested this approach, which harkens back to the spirit of early efforts at constructing a balanced global trading system. During the Bretton Woods negotiations of 1944, economist John Maynard Keynes proposed a global mechanism whereby tariffs would be imposed on nations that ran excessive trade surpluses, thus ensuring that trade between nations remained balanced. The United States, which was running a trade surplus and expected to continue doing so, rejected the idea.

The Import Certificate

For a market-based alternative to a global tariff, policymakers could also consider a proposal suggested by Warren Buffett in 1987, and again in 2003 and 2016: create a “cap-and-trade” system for imports. Buffet proposed the creation of Import Certificates (ICs) that would grant American firms the right to import a given value of goods. The government would issue ICs to American exporters based on the value of their exports, and those exporters could sell their ICs to firms seeking to import. ICs would create a subsidy for exporters, financed by an implicit tariff on importers, which would automatically rise or fall as needed to hold exports and imports in balance. Former Senators Byron Dorgan (D-ND) and Russ Feingold (D-WI) proposed a version of this idea in their Balanced Trade Restoration Act of 2006. Ambassador Lighthizer has also suggested that this approach could be effective.

The Market Access Charge

Rather than address trade imbalances directly, policymakers could take advantage of the relationship between the current and capital accounts and focus instead on the excessive global demand for American financial assets, the sale of which finances the U.S. trade deficit. The Coalition for a Prosperous America has proposed a market access charge on foreign purchases of dollar-denominated American financial assets when the United States is running a trade deficit, driving down demand for those assets, reducing the dollar’s value, and thus making the acquisition of American goods and services relatively more attractive. The charge could increase or decrease with the size of the trade deficit and phase out when the balance of trade is restored. Senators Tammy Baldwin (D-WI) and Josh Hawley (R-MO) have formalized this proposal in their Competitive Dollar for Jobs and Prosperity Act.

Global Rules & the WTO

In The Betrayal of American Prosperity, Clyde Prestowitz notes that the World Trade Organization (WTO) was not formed to achieve the economist’s fantasy of unregulated trade, in which each nation chooses of its own accord to drop all trade barriers. Rather, it was “supposed to be a reciprocal trade agreement,” which “formally prohibits or restricts subsidies, dumping…nontransparent regulation, and a wide variety of other practices, including particularly any action that might nullify or impair the value of negotiated reductions in trade barriers.”

This does not describe the WTO’s current reality or its effect on the American economy. Nations like China routinely engage in actions that “nullify or impair the value” of the favorable trade relations that WTO members are required to extend to one another. The WTO has proven inadequate to the task of preventing these actions, or of equitably resolving the trade disputes that result. American policymakers should ensure their existing trade remedy tools are adequate to the task of protecting the national interest in trade disputes, while seeking fundamental reforms at the WTO that apply global trade rules equitably.

Ultimately, policymakers must take a realist view of the WTO’s role and capacity. The organization represents an important mechanism to facilitate trade around the world, and its default rules greatly benefit American importers and exporters who would otherwise need to rely on individually negotiated bilateral or multilateral agreements with every other nation. This convenience has value. But treating WTO rules as sacrosanct, especially when its trading partners do not, has not served America well. U.S. trade strategy must allow departures from the WTO’s defaults whenever doing so is in the national interest.

Level 1—Enforcement

U.S. law provides existing tools for imposing tariffs in response to unfair trade practices by other nations, but they often prove inadequate to deterring the practices or relieving the Americans harmed.

Antidumping (AD) and Countervailing Duties (CVD) allow a U.S. administration to provide relief to domestic businesses harmed by unfair import competition. If a trading partner is found to be dumping or unfairly subsidizing a product, duties can be added to offset the difference in price between the imported and domestic goods. However current AD/CVD law contains weaknesses that make its application difficult in cases in which countries are repeat offenders, route their products or subsidies through other countries, or seek to circumvent existing rules. These shortcomings should be remedied, as the bipartisan Leveling the Playing Field Act 2.0 seeks to do by streamlining and sharpening trade remedy processes to deliver faster relief to U.S. industries harmed in such cases.

Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974 provides a highly flexible trade remedy, allowing a U.S. administration to impose import restrictions and suspend trade agreement concessions if a trading partner’s actions unreasonably burden U.S. commerce. The United States Trade Representative made liberal use of 301 investigations in prior eras, particularly during the Reagan Administration when the WTO’s predecessor arrangement (the GATT) was proving inadequate. However, the WTO agreement reduced the potential scope of 301 actions and forbade their use on any matter covered by WTO rules. While the Trump Administration’s trade policy signaled renewed comfort with 301 actions, which the Biden Administration has also embraced, their use remains unusual. Congress should pass a resolution expressing support for increased use of 301 actions in defense of American industry, helping to renormalize their use and sending a strong warning to trading partners to play fair. Conversely, policymakers should reject efforts like the Trade Act of 2021 that would prevent effective use of 301 actions.

Level 2—New Tools

If a global economy governed by WTO rules is to have any prospect for long-term vitality, the WTO will require serious reform.

The WTO’s dispute-resolution system is badly broken. Its Appellate Body routinely issues new trade “law,” never agreed to by member nations, rather than adjudicating the rare individual case as intended. The Trump Administration declined to approve appointments to the Appellate Body, effectively preventing its operation. Congress should formalize this practice and establish that it is U.S. policy not to approve such appointments, nor recognize the legitimacy of dispute resolution decisions until the system is reformed. One straightforward reform would replace the Appellate Body with an arbitration system that empanels one-time tribunals as needed to rule on specific cases, with rulings relevant only to the parties concerned.

The WTO offers developing nations Special and Differentiated Treatment (SDT) status, which allows them special advantages. SDT is a founding principle of the WTO, reflecting the belief that trade is essential for promoting development in poorer countries. But nations self-declare their status and major economies like China continue to claim it. This practice must end, replaced by objective economic criteria that reasonably limit SDT to the developing countries that merit it. The Trump Administration formally directed USTR to seek reform of SDT practices, and to ignore self-designations as “developing” when countries unreasonably claim it. Congress has also demanded reform though bipartisan resolutions. H.Res 746, introduced in 2019 by Rep. Ron Kind (D-WI) and Rep. David Schweikert (R-AZ), was adopted by the House Ways and Means Committee in 2020. S. Res 101 from Senators Rob Portman (R-OH) and Ben Cardin (D-MD) takes a similar stand. Ambassador Katherine Tai, the Biden Administration’s USTR, has testified to Congress that SDT should not be abused by major economies; administration policy must follow her lead. If reform is not achieved, Congress could consider defining inappropriate claims to SDT as an unfair trade practice subject to Section 301 or other trade remedy action.

Level 3—A New Balance

The United States today is expected to abide by its WTO obligations, even as major trading partners like China routinely ignore their own obligations. The WTO has been unable to remedy the situation; on the contrary, it has sometimes ruled against the United States for responding in defense of its own interests. While the intent of the WTO is to apply broad, equal rules to all members, the global trading system’s reality is a hodgepodge of bilateral and multilateral agreements, tariffs and other non-tariff barriers. Why treat a system as sacrosanct that does not and cannot meet its stated goals or apply its own rules equitably?

The “nuclear option” proposed by some policymakers, of withdrawing from the WTO altogether, would carry significant costs. The U.S. has Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) with 20 countries, but most nations engage in trade with the U.S. under the auspices of the WTO. Leaving would force the trillions of dollars in American economic activity that occurs today within the WTO framework into a murky legal purgatory. Alternatively, some policymakers have called for the reverse approach: expelling nations that are in constant violation of WTO rules and principles or other international norms. But the WTO rules make no provision for expulsion of a member, and while a supermajority of WTO members could theoretically establish such a process, that is unlikely to occur.

A better approach for America is to continue enjoying the benefits of WTO membership and its default framework while asserting the right to depart from WTO defaults as needed. The U.S. has already taken steps in this direction through its increased use of 301 tariffs. The only consequence that the WTO can impose is to grant other nations the right to retaliate in kind against the United States, which of course they already feel free to do whenever they choose.

One WTO rule for the U.S. to reconsider is the requirement that each member extend Most Favored Nation (MFN) status to every other member, meaning that each member benefits from the most favorable terms the United States offers to any member. Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) are exceptions to the rule, but only if they are “comprehensive”—a steep threshold. The United States should ignore this WTO obligation, which has contributed to the WTO’s decades-long inability to achieve a new negotiated agreement, which in turn has driven members to litigation through the broken dispute-resolution system. American policymakers should engage in other kinds of negotiation where desired and reach agreements with select nations that are not extended to all WTO members. The bipartisan Trading System Preservation (TSP) Act, for example, takes this approach by allowing the U.S. to negotiate sector-specific plurilateral agreements not subject to MFN rules.

Likewise, absent the formal expulsion of a WTO member, the United States should choose unilaterally to treat certain other WTO members as if they were not members. The bipartisan No Trading with Invaders Act, introduced in response to Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, would permit the United States to revoke Permanent Normal Trade Relations (PNTR, the U.S. term for MFN) for any currently or formerly Communist nation that aggresses against a WTO member. Other bipartisan bills have aimed to directly suspend Russia’s MFN status, an approach supported by President Biden. Policymakers should embrace this general approach and expand it to address serial abusers of the international trading system.

While declining to acknowledge another WTO member’s status as a member is not contemplated under WTO rules, the concept has precedent in the organization’s foundational agreement. Article XIII of the World Trade Agreement allows member nations, at the time a new nation becomes a member, to decline to apply the Agreement with respect to that member—to declare, in essence, that the two nations will not treat each other as fellow WTO members. As written, Article XIII permits non-application only at the outset of a new member’s accession. But its presence in that context demonstrates that refusal to recognize another nation’s WTO membership poses no threat to the WTO’s general framework.

Immigration

Globalization’s paradigm idealizes not only the flow of goods and capital across borders, but the flow of labor as well—the same principle that unconstrained flows will yield efficiency and growth is supposed to hold here as well. Likewise, finding a new balance for the American economy requires consideration of immigration, too. Labor flows respond to flows of goods and capital; American firms constrained from pursuing labor arbitrage offshore will turn quickly toward bringing low-cost foreign labor into the domestic market.

The politics of immigration, however, are quite distinct. Unlike the failed bipartisan consensus on global trade, which witnessed little debate, immigration battles have been pervasive and resulted in stalemate. Policymakers reconsidering globalization will have to overcome that paralysis, and answer the unanswered question: What is immigration policy for?

Immigration policy appropriately and inevitably concerns not just economic questions but questions about moral commitments, national character, geopolitical objectives, and more. Insofar as goals are non-economic, economic analysis will only get so far. But policymakers do have an obligation to consider the economic purposes and effects of immigration policy, and in formulating an approach to globalization they must account for immigration. A balanced immigration policy should encourage the flow of global talent into the American labor market that contributes to the nation’s economic dynamism. At the same time, it should strive to maintain a tight labor market that preserves worker power and induces domestic investment in productivity growth.

U.S. immigration policy fails on both counts, to the detriment of the American workforce—including those temporary workers and permanent immigrants who join it. The current system makes heavy use of easily manipulated guestworker programs that exploit temporary workers, subjecting them to low pay and often to outright abuse (including forced labor) from which they have little protection or recourse. Employers use the programs to place downward pressure on wages, import foreign labor to compete with American workers who could do many of the jobs, and ultimately to offshore those jobs. Meanwhile, the permanent immigration system gives little consideration to economic consequences, preventing policymakers from using it to maintain labor-market balance in the long run or effectively welcome the “best and brightest” to the country.

Policymakers should immediately address abuses of guestworker programs. In the long run, policymakers should pursue an immigration system that maintains a tight labor market and tilts the composition of permanent economic immigration toward those most likely to meet critical economic needs. Giving effect to these policy choices will require the capacity for enforcement.

Level 1—Enforcement

The sine qua non of any immigration system is the political will and practical ability to enforce it. Achieving this, on its own, would represent major progress in American immigration policy. Enforcement methods, like immigration policy generally, raise moral as well as economic questions that policymakers must consider. But no new approach, no matter how well designed, can succeed unless it can actually be implemented.

A benefit of the focus on immigration’s economic effects is that, where labor market access is concerned, violations are jointly committed by immigrant and employer, offering better opportunities for both deterrence and sanction. Often, it is the employer who is the easier and more appropriate target. Workers who violate immigration law do so in search of opportunity. Employers do so to increase profits and avoid accountability, both by employing people illegally and making illegal or abusive use of guestworker programs. Policymakers should increase penalties for both misuse of legal immigration programs and employment of illegal immigrants, and increase funding for investigation and prosecution. A mandatory “E-Verify” system to check the legal status of new hires would both impose a clear obligation on employers to comply with the law and also provide them with the tool they need to do so.

Level 2—New Tools

American companies routinely substitute the global labor supply for the domestic one by abusing guestworker programs to displace incumbent workers while exploiting the temporary foreign labor they import, thus distorting labor markets and leaving both domestic labor and temporary workers worse off. The primary vehicle is the H-1B visa—meant for high-skilled temporary labor—which has earned the name “the outsourcing visa.” There are about 600,000 H-1B holders in the United States with the number issued annually capped at 85,000. About 40% of these are issued to 30 companies, more than half of which are top outsourcing companies like Infosys, Tata Consultancy Services, and Cognizant, which use them to replace incumbent American workers with temporary foreign workers paid less than market wages and unable to change jobs. These firms also use H-1B visas to facilitate the actual offshoring of American jobs: in many cases, guestworkers now trained in a given job—often by the laid-off workers they displaced—return to their country of origin and continue performing the function for much lower wages.

The Department of Labor (DOL) and Congress should take several immediate steps to remedy this. DOL should begin enforcing the legal requirement that employers pay the wage rate paid to other similarly situated employees. This rule, intended to ensure that employers do not underpay temporary workers and thus suppress overall wages, has historically not been enforced. If the administration does not begin enforcement, Congress must hold the administration accountable via its oversight function, and by amending the visa’s underlying statute if necessary. Congress should also close the loophole that allows a “secondary employer” to hire an H-1B visa holder for a job that could be filled by an American worker, simply by hiring an outsourcing firm that is itself technically the visa holder’s employer of record. Secondary employers should be required to demonstrate their need for the foreign worker before retaining the outsourcing firm to provide one.

Currently, 85% of H-1B visas are awarded to entry-level and junior workers. Preference should be given to H-1B applicants based on skill rather than lottery, tilting allocation towards those H-1B workers whose expertise employers are most likely to legitimately need. A Department of Homeland Security rule proposed during the Trump Administration that would have allocated H-1Bs by wage level was challenged in court and subsequently withdrawn. Congress should revisit the question, perhaps by requiring that H-1B visas be allocated by demonstrated skill and education levels. The bipartisan H-1B and L-1 Visa Reform Act, introduced by Senators Dick Durbin (D-IL) and Chuck Grassley (R-IA), respectively the Chairman and Ranking Member of the Senate Judiciary Committee, would do this.

The H-2A visa, meant to allow temporary agricultural workers into the United States, also suffers frequent employer abuse—as do the visa holders. Exploitation of H-2A workers is extremely common and the opportunity to pay lower wages and exercise increased control of employees also leads to discrimination against American workers seeking agricultural employment. The H-2A program is not subject to any statutory numerical cap and has been expanding in recent years, surpassing 200,000 visa issuances for the first time in 2019. Congress should immediately cap this program at its current levels and establish a schedule for its gradual and predictable phase-down, producing the necessary incentives for the industry to invest in raising productivity and creating jobs that Americans want to do.

In the meantime, policymakers should review the Adverse Effect Wage Rate (AEWR), which is set for H-2A workers, to ensure that those workers do not depress domestic wages or displace American workers.

Level 3—A New Balance

Assessing the labor market’s needs, and a prospective immigrant’s fit, is a much harder task in permanent immigration than in temporary immigration. No one knows what specific industries will require in the future, nor whether an immigrant qualified to meet a current need will stay in that field. Screening and prioritization must focus on the best available markers of potential economic contribution. Many nations evaluate prospective immigrants’ potential economic contributions through a state-administered point system based on markers like education, age, language ability, entrepreneurial experience, exceptional achievements, and so on. While an imperfect predictor of individual economic contribution, such systems can perform well in the aggregate—and certainly better than a system that makes no attempt. The U.S. should adopt this approach. A points-based merit visa system has attracted support in proposals ranging from the bipartisan “Gang of Eight” immigration overhaul in 2013 to the RAISE Act, introduced by Senators Tom Cotton (R-AK), David Perdue (R-GA), and Josh Hawley (R-MO) in 2017.

A points-based system should account for a substantial share of annual permanent immigration, but an effective system would accommodate many immigrants admitted on other bases as well. Economic effects are one set of considerations for immigration policy, but not the only one. Nor does a points-based system have the only claim to supporting economic objectives. The unpredictable but quintessentially American story of the unskilled, penniless immigrant who goes on to found a successful nationwide business or make groundbreaking discoveries is an important part of the national heritage as well.

Conclusion

Policy choices guided by an ideological commitment to the unfettered flow of goods, capital, and labor produced today’s globalization. Learning from the experiment’s failure, policymakers can make different and better choices. Enhancing existing tools and creating new ones will help to mitigate globalization’s harmful effects but will require broad and aggressive market interventions. In the long run, America’s goal should be to move beyond globalization, to a system that preserves a free and flourishing domestic market, interacts with the global economy in a balanced way, and better serves the nation’s economic interests.

Recommended Reading

Talkin’ (Policy) Shop: Globalization

On this episode of Talkin’ (Policy) Shop, Oren and Chris discuss globalization—how we got here, the problems it has created, and what policymakers should do now.

New Report Finds Globalization Failed to Deliver Economic Growth and Good Jobs

PRESS RELEASE—New American Compass report on the failed experiment of globalization and an online quiz that exposes the bipartisan Uniparty’s witless case for globalization

Where’s the Growth?

The era of globalization has coincided closely with the onset of precisely those problems that a clear-eyed analyst might have predicted and delivered outcomes contrary to the ones its ideologues envisioned.