RECOMMENDED READING

In less than 24 hours I will be wheeling my bag through the large revolving doors of the hospital, through the Covid screening point, and up the elevator to the ninth floor to deliver my fifth child due to a medically-necessary induction.

Things are more or less ready, and so I find myself ruminating on a topic I’ve had much reason to think about in recent years. That is, the messy intersection of motherhood and paid work—the burdens of each and their respective rewards, the choices women make (particularly in a pandemic) and the ways these choices shape our identities.

Though I know there’s been plenty of ink spilled on the topic, there’s no doubt a need for even more reflection—and more needs to be done to support mothers and fathers with paid family leave and, for working parents, affordable, quality child care. As Biden said when unveiling his child and elder care plan, “If we truly want to reward work in this country, we have to ease the financial burden of care that families are carrying.”

But recent headlines, like this article in USA Today about the pandemic-induced challenges facing women during “America’s first female recession,” fall flat. What could be a rich, and needed, conversation becomes one dimensional. Terms like “occupational segregation” are too simplistic and don’t account for the variety of preferences women have when it comes to the division of paid work and at-home childcare and how those choices play out in the landscape of employment. What if at the root of some of the disparities in men’s and women’s work is not victimization but a more empowered reality—women acting on their own preferences?

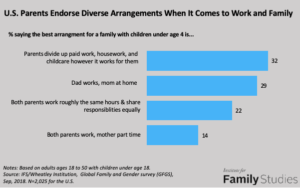

Research from the Institute for Family Studies, where I am a fellow, demonstrates that when it comes to work-family balance, there is no “one-size-fits-all” model. The diversity of preferences is astounding and should keep all of us humble when proposing policy solutions. What works for some American families will not work for others.

My own experience has been varied and continues to vary with each child. I’ve worked full-time, part-time, as a gig worker, and not at all. I always hoped to have a big family—a family of 10 whom I admired since childhood were a big influence on me—and so I’ve relished the flexibility of being able to move from one type of work arrangement to another to accommodate our changing family dynamics and needs.

There have definitely been trying periods of transition, like the identity crisis that came with a diminution of paid work. (But it was ultimately a meaningful process that moved me to a healthier place of self-understanding. One takeaway is that we as a society need to do better about acknowledging the value of child care, whether done by a paid worker or by a parent or relative at home, instead of insinuating that the value of the work derives from something as arbitrary as a paycheck.) Overall, I’ve been happy with how my husband and I have been able to co-raise our children and work together to financially provide for our family in at times ways somewhat atypical but that work well for us.

That said, I know that is not the normal experience, particularly for low-wage workers. One of the tragedies of the pandemic is the way it has taken work away from people, and for women with children in particular who face school and child care shut downs, the way it has taken away latitude of choice. As the USA Today piece highlights, women have found themselves doing less paid work and more child care during this time, and when this is imposed by circumstances as opposed to freely chosen that is extra challenging, even for married women with employed partners, let alone for single mothers who are sole breadwinner.

In many ways, the pandemic has made more acute the challenges that mothers of all backgrounds are always facing in the world of paid work. We should continue to highlight and respond to these challenges. But my hope is that in that conversation we don’t lose sight of the diversity of women’s preferences and in so doing trade a complex reality for stereotypes.

Recommended Reading

A World Tour of Family Benefit Programs

American enthusiasm for a per-child family benefit has grown, but details matter and proposals differ widely—as do the programs already established in other nations.

The Family Income Supplemental Credit

This paper presents the case for a per-child family benefit that would operate as a form of reciprocal social insurance paid only to working families.

Home Building Survey Part II: Supporting Families

American attitudes about family structure vary widely, but most families see a full-time earner and a stay-at-home parent as the ideal arrangement for raising young children.