Conservatives should favor limited government, not reflexive tax cuts

More From This Collection

Kevin Hassett, chair of President Donald Trump’s Council of Economic Advisers (CEA), brought good tidings to his professional colleagues gathered at the 2019 Annual Meeting of the American Economic Association (AEA). Just over a year after passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), the results were in: The tax cuts had spurred business investment and growth as predicted. So clear was this evidence “for the headline things that we model with real science,” he explained, that “if you say the tax cuts aren’t working then you’re kind of in some kind of denial that you should think about.”

There was just one problem. The figures that he cited for the economy’s performance in the first three quarters of 2018 were preliminary, subject to revision as the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) gathered more data. As better numbers trickled in, TCJA’s positive results vanished. The CEA’s own charts, updated with the revised figures, would show that their models were wrong, business investment had failed to surge, and growth had perhaps even slowed.

What TCJA did deliver, unquestionably, was declining tax collections and rising deficits. In 2018–19, at the peak of the longest economic expansion on record, as the unemployment rate fell below 4%, real tax revenue was lower than in the final two years of the Obama administration. If that result sounds familiar, it should. The Bush tax cuts of 2001 and 2003 delivered the same, failing to boost investment or economic growth, while leaving real tax revenue in 2003–04 well below the final two years of the Clinton administration. (For detailed discussion of these data, see Tax Cut Did What?)

Nevertheless, as if compelled by some supernatural spell, the GOP continues building its economic agenda around tax cuts and making outlandish promises about their power. Speaker of the House Paul Ryan was a committed “fiscal conservative,” yet his major legislative achievement was a major increase in the budget deficit. Watching a pandemic sweep the globe and send the United States into lockdown, Ambassador Nikki Haley’s reaction was: “As we are dealing with changes in our economy, tax cuts are always a good idea.” With UK markets spiraling downward and Prime Minister Liz Truss’s government collapsing in the wake of her own ill-advised tax-cut proposal, Michael Strain, the director of economic policy studies at the American Enterprise Institute, lauded her leadership as “a model that American conservatives could follow”; the Wall Street Journal editorialized, “The dumbest argument is that Ms. Truss’s fall is a warning to U.S. Republicans not to cut taxes.”

George H.W. Bush was more right than he could have known that a zombie Reaganomics would haunt his party long after any semblance of a serious conservative policy had expired.

George H.W. Bush may have been wrong in 1980 to criticize Ronald Reagan’s agenda for escaping the stagflation of the 1970s as “voodoo economic policy.” But he was more right than he could have known that a zombie Reaganomics would haunt his party long after any semblance of a serious conservative policy had expired. Is an intervention required, or an exorcism?

Why Conservatives Cut Taxes

A common explanation for the Republican Party’s tax-cutting obsession is that it follows naturally from conservative principles. Conservatives favor smaller government and have greater faith in markets, ergo tax cuts will always be central to the GOP agenda. Such analysis conflates two distinct rationales for lower taxes: limited government and economic growth. The conservative commitment to limited government, and to advancing the common good while imposing the lowest possible burden on taxpayers, is vital. Conservatives should want to reduce taxes where that can be done consistent with the equally important principle that in normal times a nation should pay for what it consumes rather than purchase on credit and pass the burden to future generations.

Using tax cuts to generate economic growth is a different project altogether, and one that conservatives must recognize can be worthy in some circumstances and foolish in others. The failure to analyze proposals critically, instead confusing the policy of supply-side tax cutting for some timeless principle, has disastrously malformed the GOP agenda for a generation. It has yielded costly and ineffective policies that discredited conservatives when in power. And it has made impossible the task of building political support for fiscal responsibility. Conservatives will have to break the spell if they want to build a governing majority and govern effectively.

To the market fundamentalist, a tax cut may always be a good idea. The conservative, by contrast, begins from Edmund Burke’s advice that “circumstances give in reality to every political principle its distinguishing color and discriminating effect. The circumstances are what render every civil and political scheme beneficial or noxious to mankind.” In at least three situations, a tax cut is indeed the right economic policy.

Revenue Maximization

The first is a narrow case: when tax rates are above the revenue-optimizing level. As the famous “Laffer Curve” illustrates, a tax rate of 100% would be unlikely to raise much revenue because no one would have an incentive to generate income that would go entirely into the government’s coffers. A tax rate of 0% would likewise be a poor revenue raiser. As the tax rate decreases from 100%, or increases from 0%, revenue collection rises. Somewhere between those two extremes is the rate that generates the most tax revenue. Cutting a tax rate higher than the revenue-optimizing level back to that level can both improve incentives and raise more revenue—a win-win.

This case is robust in theory, but rarely presents itself in practice. Reducing the top marginal rate for individual taxpayers from 91% to 77% in 1964 probably qualified. Reducing it from 70% to 50% in 1982 might have qualified. Reducing it from 39.6% in 2000 to 35% in 2003 surely did not.

The Laffer Curve is real, but as deployed in tax-cutting debates it functions mainly as propaganda.

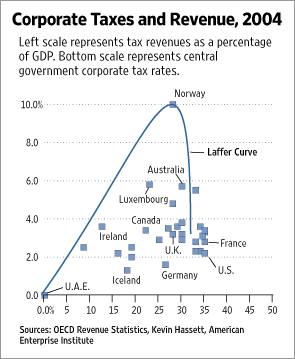

Unfortunately, overeager proponents often confuse the Laffer Curve’s hypothetical salience for a general proposition that cutting taxes will raise revenue. As Senator John McCain put it during his 2008 presidential run, “Tax cuts, starting with Kennedy, as we all know, increase revenues.” Around the same time as McCain’s remark, the Wall Street Journal’s editorial board set a new mark for outlandish misuse of a Laffer Curve with a curve drawn through data on corporate tax rates and revenue that seemed to show obvious outlier Norway at the curve’s very peak and a corporate tax rate any higher sending revenue plunging quickly toward zero. The Laffer Curve is real, but as deployed in tax-cutting debates it functions mainly as propaganda.

What even the Journal seems accidentally to have gotten right is that capital gains and corporate income taxes do tend to have lower revenue-optimizing rates than individual income taxes because investors and corporations have many more options for how, when, and where to recognize income. For instance, the Penn-Wharton Budget Model estimates that the revenue-optimizing rate for the capital gains tax is 33% or 42% depending on other policy parameters. Lowering the rate from 40% in 1978 to 20% in 1981 may have increased revenue. Lowering it from 21% to 16% in 2003 did not. Estimates for the corporate tax rate’s optimum are generally between 25% and 30% and sensitive to changing rates around the world. A reduction of the 35% U.S. corporate rate likely had the potential to increase revenue. TCJA’s reduction all the way to 21% caused corporate tax revenue to fallsubstantially.

Incentives for Growth

The second, broader case for tax cuts is the traditional “supply-side” argument: If high marginal tax rates are discouraging economic activity, lower ones could generate a boom. When the Tax Reform Act of 1964 reduced the top individual rate from 91% to 77%, the take-home value of each dollar earned by a taxpayer in the top bracket more than doubled. When the top rate declined from 70% at the start of Ronald Reagan’s presidency to 28% at the end, the take-home share of a dollar earned more than tripled. Those effects could be powerful.

But as with the Laffer Curve, the case for a supply-side tax cut is contingent. To what extent are tax rates discouraging economic activity? How much would the proposed cut alter the incentives? What response would such an alteration generate? Temporarily reducing already much lower rates by a few percentage points, as in the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts or the 2017 tax cuts may accomplish little, even as it costs quite a lot. Bringing the capital gains rate from 40% to 20% in the face of stagflation is rather a different matter than bringing it from 21% in 2002 to 16% in 2003.

A number of other factors can also complicate the “incentives” story. For instance, especially for households, a tax cut has what economists call both a “substitution effect” and an “income effect.” On one hand, lower rates and the opportunity to keep more of the next dollar earned might make working hard to earn more income an attractive proposition. On the other hand, if lower rates translate into higher household income for work already being done, workers may be disinclined to exert greater effort to earn more. With additional money already coming into the bank, the household might prefer to spend relatively more time on leisure than on labor.

For corporations, the question of how and when they decide to invest has proved far from straightforward. The standard economic model holds that each firm knows its “cost of capital” and will invest in any project where the risk-adjusted return is expected to exceed that cost. Cutting the corporate tax rate effectively lowers the cost of capital or increases the expected return and should therefore cause more projects to go forward. But in practice, firms only pursue projects that clear much higher return hurdles and many have shown an inclination to return cash to shareholders through dividends and buybacks even when profitable and productive investment opportunities exist. In that context, a lower tax rate might lead simply to yet more cash handed back.

Insofar as a lower tax rate does lead firms to pursue some previously unattractive projects at the margin, the nature of those projects might also matter a great deal. The assumption that tax cuts are a wise mechanism for spurring productive investment and growth takes all investment to be equal—an extra billion dollars invested merging two firms and laying off workers, offshoring production, or building another meal-delivery app must be as good as an extra billion spent building advanced semiconductor manufacturing facilities or developing a rare-earths mine. Historically, economists have assumed just that. But in an economy that has more than enough of the former unproductive investment and far too little of the latter productive type, and where a lower tax rate will primarily yield yet more of the former, tax cuts are the wrong tool. A committed supply-sider would look elsewhere. (See Chris Griswold’s essay, “Rebuilding the Supply-Side Platform.”)

Finally, the wisdom and effect of tax cuts will depend on how they are funded. If deficits rise and the government has to borrow more, any benefit of improved incentives may be offset.

Finally, the wisdom and effect of tax cuts will depend on how they are funded. If deficits rise and the government has to borrow more, any benefit of improved incentives may be offset. Debates rage among economists over how, if at all, to account for this effect. Especially on the right-of-center, where the wisdom of deficit-financed supply-side tax cuts is an article of faith, models tend to minimize the question of what a tax cut costs. At the extreme, in the analyses published by the Tax Foundation, tax cuts are literally free. They lead to higher debt, of course, but this has no impact on estimates for growth and employment and income. Simply cutting all taxes to zero would generate a remarkably favorable growth projection.

That may seem implausible because it surely is. Indeed, the results of recent deficit-financed supply-side tax cuts suggest that the more skeptical models provide a better way of understanding the tradeoffs. For instance, in his presentation to the AEA’s Annual Meeting in 2019, Kevin Hassett celebrated the early estimates of 2018 GDP growth for achieving precisely the gains that his preferred models predicted would follow from TCJA—an increase of roughly 1.2 percentage points. Economic growth for Q3:2009 through Q4:2016 had averaged 2.2% and the estimate for 2018 growth was 3.3%. An alternative model that estimated TCJA’s likely growth effect at 0.0 to 0.1 percentage points and thus 2018 growth of roughly 2.2% was “a bad choice of model.” In fact, after BEA revised its data, 2018 growth stood at 2.1%.

Keynesian Stimulus

A third case for tax cuts is not supply-side at all, but rather Keynesian: putting more money in the pockets of consumers can spur demand and thus growth. This case has nothing to do with the “supply side,” but can be a compelling rationale during an economic downturn. For instance, the 2001 Bush tax cut was in many respects an effort to address the ongoing recession by increasing household income. Tax cuts intended to have supply-side effects may also, in the short-run, have a Keynesian demand-side effect as well. Insofar as the years after TCJA saw a tight labor market and rising incomes, but not the higher investment and growth that a supply-side tax cut should have generated, the best explanation may be that the economy was experiencing an unsustainable “sugar high” from what amounted to excess borrowing and spending.

Well-designed tax cuts alongside direct government spending can be an effective stimulus strategy, but they will bear little resemblance to the supply-side tax cuts generally popular on the Right.

The problem with tax cuts as Keynesian stimulus is that they are often poorly targeted. High-income households pay the vast majority of taxes and so will tend to benefit most from rate reductions, but they will also tend to have a low propensity to spend any windfall. A tax cut focused squarely on lower-income households may get spent but, especially in a recession, it may also be used to pay down existing debt, in which case the policy’s effect will be only to convert private borrowing into public borrowing. Well-designed tax cuts alongside direct government spending can be an effective stimulus strategy, but they will bear little resemblance to the supply-side tax cuts generally popular on the Right. And they are difficult to justify in the midst of a healthy business cycle, as was the situation in 2017 and with the myriad proposals being advanced by presidential candidates in 2023.

Tax Cuts as Effect, Not Cause

Current tax rates and the nature of current economic challenges leave little scope or justification for yet another supply-side tax cut. Conservatives should not abandon the supply side—to the contrary, the U.S. economy has severe supply-side problems that recent tax cuts have done nothing to address but that a supply-side economics properly understood would be far better positioned to solve. But the time has long since passed for abandoning the rhetoric and reasoning of tax cuts that “pay for themselves” or “unleash growth.” Recitation of those dogmas in the 2020s, divorced from evidence of their plausibility, is the opposite of conservative.

Cutting taxes should be the reward for a job well done growing the economy, adhering to fiscal discipline, and limiting the size of government.

What would be conservative, politically attractive, and the basis for governing well, is to define further tax cuts as a goal that can be realized subject only to certain conditions. Cutting taxes should be the reward for a job well done growing the economy, adhering to fiscal discipline, and limiting the size of government. The conservative commitment to those objectives remains vital as ever, but therein lies the case for bringing the federal budget into balance, not for cutting taxes. Spending determines government’s size, its economic force, and the cost borne by citizens, whether they agree to overt taxation or not. The higher inflation of recent years and surging interest payments on our skyrocketing national debt both serve as reminders that, one way or another, taxpayers are inevitably on the hook for the resources that government consumes.

Some anti-tax activists have attempted to make the case that cutting taxes first, by “starving the beast,” will lead to limited government second. Empirically, that has not been true—tax cuts have not reined in spending. As a political matter, it is unwise. Delinking taxation from spending sends the message that big government’s generosity is free, at which point is also begins to appear much more attractive. Conservatives should insist upon a political culture in which voters and politicians understand that voting for the spending also means paying for it.

Under the curse of voodoo economics, political leaders behave in strange and counterproductive ways, harming their own popularity, disregarding the economy’s needs, and inadvertently promoting bigger government. Economists make easily falsified claims and build obviously incorrect models. Some conservatives are waking up to these realities, and now they must find a way to make those around them snap out of it.

More From This Collection

The Curse of Voodoo Economics

Conservatives should favor limited government, not reflexive tax cuts

Rebuilding the Supply-Side Platform

Boosting American investment and production when tax cuts will not

Learning the Lessons of Supply-Side Economics

Conservatives should bring supply-side thinking to issues beyond business investment