RECOMMENDED READING

Supreme Court Justice Ginsburg’s death roiled an already unsettled the political scene. A pitched battle is underway over who will succeed her and when.

David French urges Republicans to stand on principle. He sketches a way forward that has Trump nominating a replacement before the election. The Senate will then hold hearing but refrain from voting until after November 3. If Trump wins, a Republican majority in the Senate will vote to confirm. If he loses, French has Biden promising not to pursue a court-packing strategy once in office, and in exchange Mitch McConnell will not pursue a lame duck confirmation, keeping the seat open for Biden to appoint his own choice.

Perhaps this course of action is wisest. Others have adopted this view as a path toward sustaining what is left of the bi-partisan consensus about the importance of maintaining the integrity of our institutions. But the proposal reflects prudential judgments (as Adam White, who holds a similar view, recognizes). It is not an application of principle.

One of the foundational principles of leadership is to preserve the realm. This has obvious relevance in our polarized situation. We sense that the social contract in American is fraying. Pitched battles over Supreme Court Justices are evidence of the weakening of civic friendship, the trust that one’s political adversaries are, at the end of the day, pulling in the same direction, even if pursuing quite different policies.

Many urge courses of action that will best fend off further rancor and more polarization. This is a noble ambition. But the way forward is always complicated.

Consider an analogy from diplomacy. The promotion of peace is a core principle. It often requires concessions and efforts to meet halfway in the face of differences. There are times, however, when concessions amount to appeasement. In such a situation avoidance of conflict can lead to greater, more destructive conflicts down the road. Thus, the principle (promote peace) leave open the question of whether to make concessions or respond forcefully and risk open conflict.

Another important observation: Political give-and-take is intrinsically complex, and the outcomes are unpredictable. In the case of Justice Ginsburg’s replacement, the appointment of a conservative jurist will outrage liberals. (This will be as true if confirmation comes in October, December, or February 2021.) The anger will stem from the fact that since the Warren era, liberal have presumed that the Supreme Court is “their” institution. Any change in “ownership” is therefore a violation of “constitutional norms,” at least as liberals view it. Such a claim is not baseless. A Court with a substantial majority skeptical of key elements of postwar constitutional law (Roe v. Wade, for example) will have the power to change those norms.

This liberal anger may lead to efforts to enlarge the Court (court packing). But a consequence of this strategy may be the diminishment of the Supreme Court’s nearly sacred authority over American public life. Is that such a bad thing? Diminution might stimulate Congress to recover legislative initiative. It might lead to greater judicial federalism. And this might be the best way toward a more stable bipartisan peace treaty, not appeasement of partisan fury in the present moment.

David Leonhardt at the New York Times was right on cue. After Ginsburg’s death, he floated the idea that lifetime tenure for federal judges might not be the greatest idea. Perhaps we need limited terms or mandatory retirement at a certain age. I favor lifetime tenure, but that’s not my point. What’s interesting is that, faced with a potential supermajority of conservative jurists, a spokesman for the liberal establishment is entertaining ideas that reduce the present power of the judiciary. Again, is this a bad thing?

I believe that one of the powerful forces driving polarization has been the Supreme Court’s usurpation of legislative authority. It has eroded democratic accountability. Moreover, I believe that our political culture is in an uproar because our leadership class has become arrogant and unaccountable. The judiciary is an unabashedly elite branch of government (and rightly so, to my mind). Degrading the Supreme Court’s authority is not, therefore, the worst outcome. It might rebalance our political culture in a more democratic direction.

My point in these musings is not to assert that I am correct and those urging Senate restraint are wrong. I simply wish to clarify the very limited role of “principle” in assessing the wisdom of one or another course of action, not just in this matter, but in nearly all policy debates.

There are two threats to good governance. One is technocratic. This view insists that political questions are scientific and technical. But this is not true. Today’s political climate is hot because we’re fighting over what kind of country we want to have. That fight is properly political, not technocratic. It turns on deep intuitions about human flourishing, not expertise.

The other threat calls for a “principled politics.” This approach escapes the uncertainty of prudential judgment by demanding that we must “stand on principle.” There are principles in civic life. They fall under the rubric of justice. But those principles frame our general ends (and stipulate what cannot be done). They rarely dictate what should be done.

For example, “limited government” is not a principle. It is an all-things-considered judgment that restraints on government power conduce to the flourishing of freedom. Like federalism, deregulation, and other political objectives, a commitment to limited government may be wise—and that’s the point. The test is whether it conduces to the ends we seek.

Assessing a course of action requires judgments of prudence, not “standing on principle.” The use of government power to break up monopoly power, restrain oligarchic interests, and address other threats represent important examples of when the general commitment to limited government does not serve the greater end of sustaining a culture of freedom.

We are living in a time of political disruption. Now more than ever we need to debate what courses of action will best promote the common good. This debate involves principles, not the least of which is our duty to promote the common good rather than private goods. Doing so requires technocratic expertise. But a good part of what we need to figure out (including how to navigate judicial appointments) concerns judgments about possibilities, consequences, effectiveness, and repercussions—the always difficult, fallible, and unavoidable uses of prudence in politics.

Recommended Reading

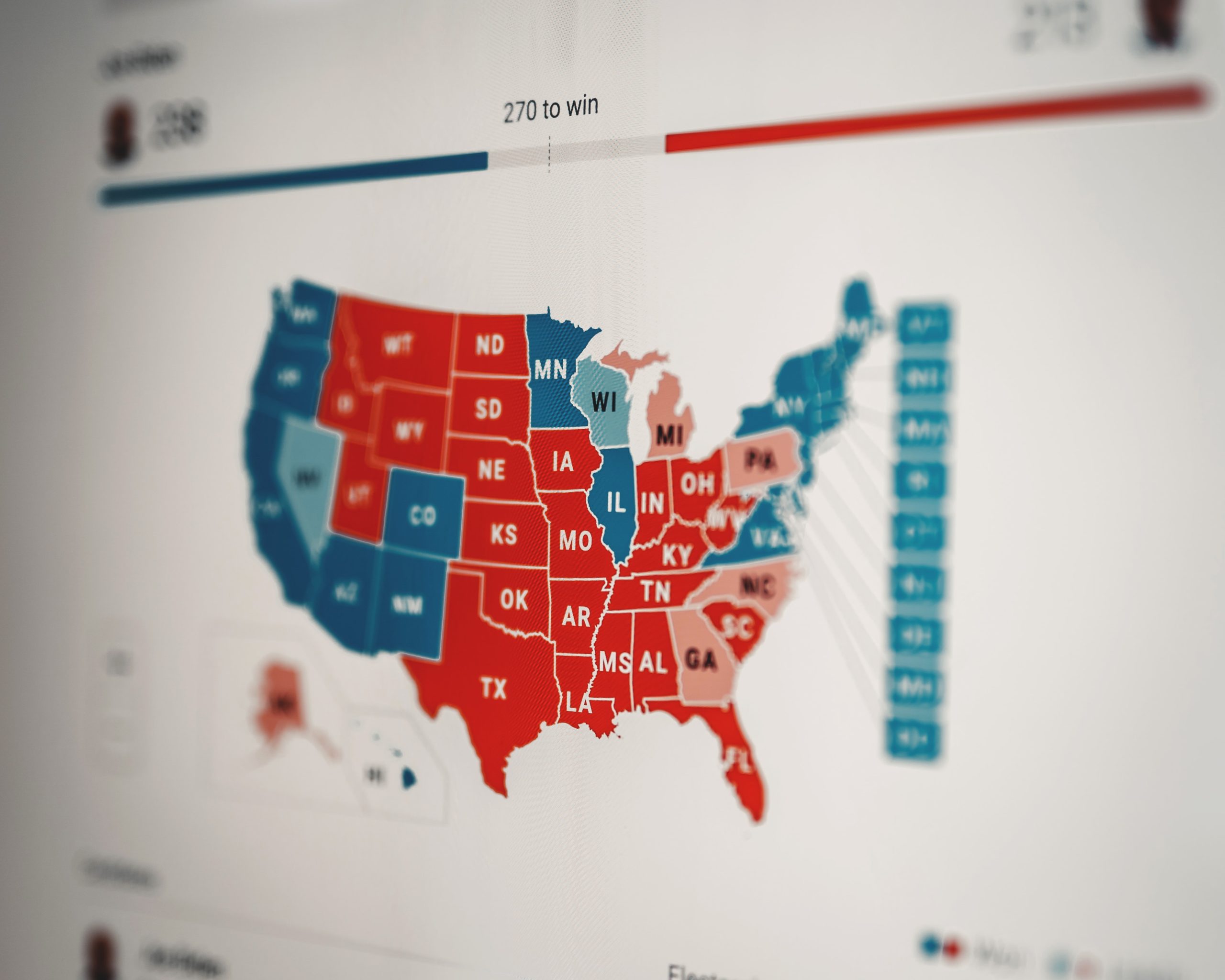

The Future of the Biden and Trump Coalitions

While Joe Biden will be the 46th President of the United States and Donald Trump will join the small club of incumbents who could not get re-elected, it’s fair to say that Biden’s triumph was not so overwhelming that it even begins to settle the question of which party will dominate the 2020s.

How Biden Could Steer a Divided Government

David Brooks discusses how Biden could successfully work with Republicans in Congress, highlighting the emerging issues that American Compass has focused on as potential opportunities for bipartisan effort.

Obama’s America Is Trump’s America Is Biden’s America

American Compass’s Oren Cass discusses the 2020 election, arguing that the outcome simply tells us who will govern us, not who we are.