An article from the Cato Institute’s Norbert Michel, titled “American Compass Points To Myths Not Facts,” is making the rounds. Having perused the Financialization chapter of Rebuilding American Capitalism: A Handbook for Conservative Policymakers, he concludes that “it’s easier than ever to ignore American Compass” and calls on conservatives to “pay very close attention to the report’s low quality of scholarship.” Our “opinion-style propaganda is born out of necessity,” he writes. “They must leave out supporting research and data because it doesn’t exist.”

As a preliminary matter, I should note that American Compass publishes volumes of research and data—the Rebuilding American Capitalism handbook is a synthesis of our analysis and recommendations and provides copious references to further reading alongside each proposal. Norbert is not unaware of this research—indeed, at one point he links to a prior debate about one of those reports—but pretending he just can’t figure out where our data comes from is clearly important to his critique.

So, let’s take at face value the lament that the handbook “provides no supporting evidence whatsoever for these claims, and it’s not difficult to figure out why—the evidence simply doesn’t support them” and see how Norbert goes about attempting to prove us wrong. He focuses on three claims we make about financialization:

A. Top Business Talent

Norbert highlights our assertion that American finance is “claiming a disproportionate share of the nation’s top business talent.” That’s wrong, he says, because “the number of people employed in the Finance and Insurance industry, as a share of total nonfarm employees, has barely budged.”

It doesn’t take a quant hedge fund manager to see that share-of-total-employment has no bearing on our claim about top business talent. As far as I know, the evidence for our actual point isn’t really disputed by anyone. As I wrote in Confronting Coin-Flip Capitalism:

Graduates of America’s top business schools provide a useful proxy for the attraction of various industries and, from 2015 to 2019, nearly 30% of graduates from Harvard, Stanford, Wharton, Booth, Kellogg, Columbia, and Sloan went into finance. In 2020, the finance industry was the most popular and offered the most generous compensation packages for graduates of the MBA programs at both Harvard and Stanford. [See also, our Guide to Private Equity.]

Engineers have likewise flocked to Wall Street, as compensation at equivalent education levels surged in finance as compared to engineering after 1980. The probability of an engineer switching to a finance career increased more than four-fold from the 1980s to the 2010s; the share of “STEM” jobs in finance doubled over that period while the share in manufacturing fell by half. Lest one think these are the engineers who couldn’t hack it in engineering, Nandini Gupta and Isaac Hacamo of Indiana University’s Kelley School of Business find that “financial sector growth attracts exceptionally talented engineers from other sectors to finance.”

B. Profits

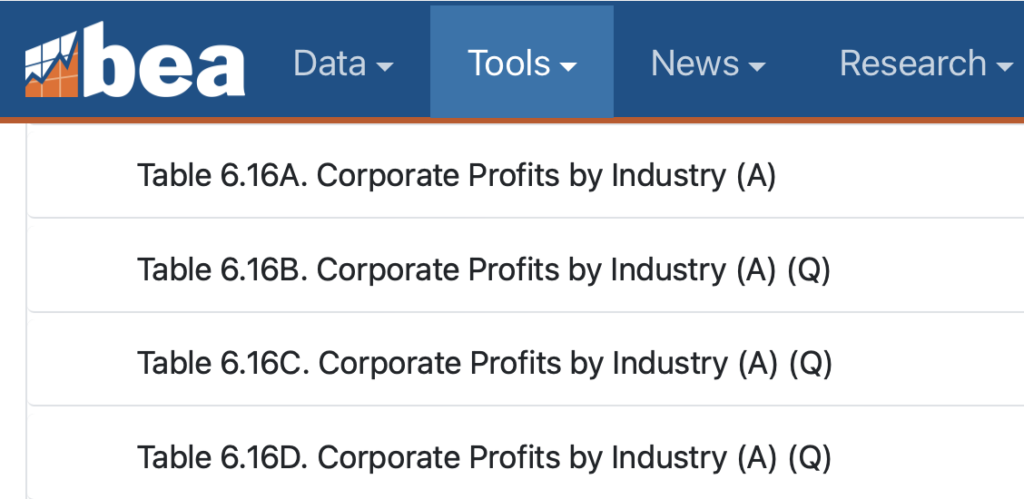

Norbert next takes exception with our assertion that finance is “claiming a disproportionate share of … the economy’s profits.” He responds, “the National Income and Product Accounts provide financial and nonfinancial company profits dating back to 1998. (See Table 6.16D, Corporate Profits by Industry.) While the annual share of total corporate profits in the NIPAs has varied, at the end of 2022 it was 18 percent for financial companies versus 82 percent for nonfinancial companies. In 1998 the share for financial firms was a touch higher (20 percent) compared to nonfinancial firms (80 percent).”

I must make three points here.

First, I don’t know whether to accuse Norbert of extreme bad faith or merely a novice’s ignorance, but I will do him the courtesy of assuming the latter. The NIPA data does not start in 1998, it goes back to 1929—it’s just divided over four tables (parts A through D). They’re right there, next to each other, in the list.

Second, the thing about accessing the full dataset is that you quickly see the trend in financialization over time. Here is Norbert’s data for financial company share of corporate profits, using the full data set and averaged by decade:

- 1950s: 12%

- 1960s: 13%

- 1970s: 18%

- 1980s: 16%

- 1990s: 23%

- 2000s: 28%

- 2010s: 26%

So, a doubling, give or take.

Third, Norbert’s focus on the 2022 data as the endpoint is unfortunately misleading—as you may be aware, the past couple of years have been somewhat unusual ones in the economy. Financial-sector profits did fall to 18% in 2022, as he notes—from 28% in 2019. That is not the result of a sudden decline in financialization, but rather a quite shocking and presumably not sustainable 50% increase in non-financial corporate profits in just three years.

C. Investment

Finally, Norbert takes issue with our claim that “actual investment has declined.” It is, he says, “also easily verified as false.”

Here, Norbert does something strange, which is to look at absolute investment dollars rather than investment as a share of GDP. He writes: “the NIPAs show that investment in fixed assets has been steadily increasing since 1970, a trend that holds even if the data is adjusted for inflation. (See Table 1.5, Investment in Fixed Assets and Consumer Durable Goods.)”

Bluntly, this is malpractice, and one can’t even presume ignorance—it’s not a question of knowing the data source, but of common sense. Of course, investment rises in absolute dollars as the American population grows and economy expands. Who would claim otherwise? The question is what has happened relative to GDP. Even using Norbert’s Fixed Asset data, the answer is:

- 1950s: 21.7%

- 1960s: 22.2%

- 1970s: 21.9%

- 1980s: 22.8%

- 1990s: 20.9%

- 2000s: 21.7%

- 2010s: 19.8%

So, a decline.

Norbert continues, “If American Compass insists on going with some other definition of investment, something like real net investment in the nonfinancial corporate sector, the evidence still isn’t in their favor.”

He should have quit while—well, not ahead, but maybe not too far behind. “The evidence” he links to here is an interesting Twitter thread from Donald Schneider, evaluating my paper on The Rise of Wall Street and the Fall of American Investment. So yes, Norbert does know what data we’re using. What’s more, Donald kicks off his thread by noting, “Net nonresidential (or business) investment is indeed the right measure to focus on,” making Norbert’s disqualifying choice of absolute-fixed-asset-dollars even stranger. And as we, Donald, and everyone else to have analyzed the issue agrees, the standard measure of net business investment as a share of GDP has declined substantially.

Now, I do think Donald raises some interesting points in his thread about inflation indices, inviting a worthwhile debate. But I also think that our novel analysis of corporate cash flows makes a compelling and independent case about declining business investment, which as far as I know has never been challenged. Overall, the balance of evidence is on our side. As I observed in “Statistical Gnosticism on the Right” of the claim that business investment has not weakened:

This claim is bizarre, and flies in the face of a broad consensus among economists and commentators. For instance, Nobel laureate Michael Spence wrote in the Wall Street Journal in 2015 that, “Business investment in the real economy is weak. … We believe that QE has redirected capital from the real domestic economy to financial assets at home and abroad.” Jason Furman, then chair of President Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers, observed the same year that, “The investment slowdown is particularly notable because it comes at a time of high cash flows for businesses and substantial accumulated earnings both domestically and overseas.” Here’s The Economist: “While gross business investment has held steady, net business investment—that is, investment adjusted for depreciation—has been in long-run decline.”

Here’s an IMF paper from 2016: “We explore firm-level data on investment and document that investment fell relative to fundamentals at the turn of the millennium—well before the Great Recession.” Here’s a Brookings paper from 2017: “We analyze private fixed investment in the U.S. over the past 30 years. We show that investment is weak relative to measures of profitability and valuation.” Here’s the American Enterprise Institute’s Jim Pethokoukis in 2019: “And while the so-so recovery after the Great Recession has seen weak business investment, the same is true across rich-country economies.”

* * *

Norbert goes on a while longer, in similar fashion. But while I still have your attention, I want to turn briefly to a broader point about the state of debate on the Right.

See, the thing is, we’ve been publishing in-depth research about financialization for three years. I’ve debated legendary distressed debt speculator Howard Marks and joined National Review’s David Bahnsen for an hour-plus discussion on his podcast. I hosted the University of Chicago’s Steven Kaplan, probably the world’s foremost academic expert on private equity, for an hour-plus conversation on American Compass’s Critics Corner, which he thoroughly enjoyed, and during which we found common ground on most of the policy proposals we discussed. Last summer, I debated the question, “Is Wall Street Good for America?” at the Intercollegiate Studies Institute’s American Economic Forum. The Financial Timespublishes our commentary on the topic.

Of course, many points of disagreement emerge in all these discussions, as they should. But among people who understand these issues and engage in good-faith debate about them, American Compass’s work is widely respected—accusations of “low quality of scholarship” and “opinion-style propaganda” are laughable, as is the suggestion that we “leave out supporting research and data because it doesn’t exist.” Few on any side would stake out the position that financialization isn’t real and finance has not grown as a share of the economy.

But. Not on the Old Right. The Old Right has shown no interest in engaging on these issues constructively for the past three years. When Norbert Michel writes an insult-laden article at Forbes, though, everyone comes pouring out of the woodwork waving pom-poms in their team colors.

People like Scott Lincicome and Alex Nowrasteh at Cato, Scott Winship and Kyle Pomerlau at AEI, and Noah Rothman at National Review retweeted Norbert uncritically. Reason’s Stephanie Slade called the article “devastating.” Jay Richards at Heritage said, “Wow. This are basic empirical mistakes” [sic]. So did they read Norbert’s analysis, feel qualified to assess his claims, and decide on that basis to endorse them? Or did they just see someone criticizing American Compass and think, “hell yeah”? I’ll let them answer for themselves.

Winship, asked which facts American Compass had actually gotten wrong, responded, “You should read the piece!” Which in its own way tells you all you need to know.

Recommended Reading

Confronting Coin-Flip Capitalism

This paper presents the case for policymakers who favor free markets and appreciate the value of a well-functioning financial system to reform the rules governing that system.

A Guide to Private Equity

An in-depth exploration of the private-equity industry: how it works, its poor performance, and its increasing risk.

The Rise of Wall Street and the Fall of American Investment

Confusion over the nature of investment is pervasive among economic policymakers and commentators, has bled into the popular culture, and threatens the nation’s future prosperity.